- Home

- Blue Talks

- A New Social Contract For The Digital Age

A new social contract for the digital age

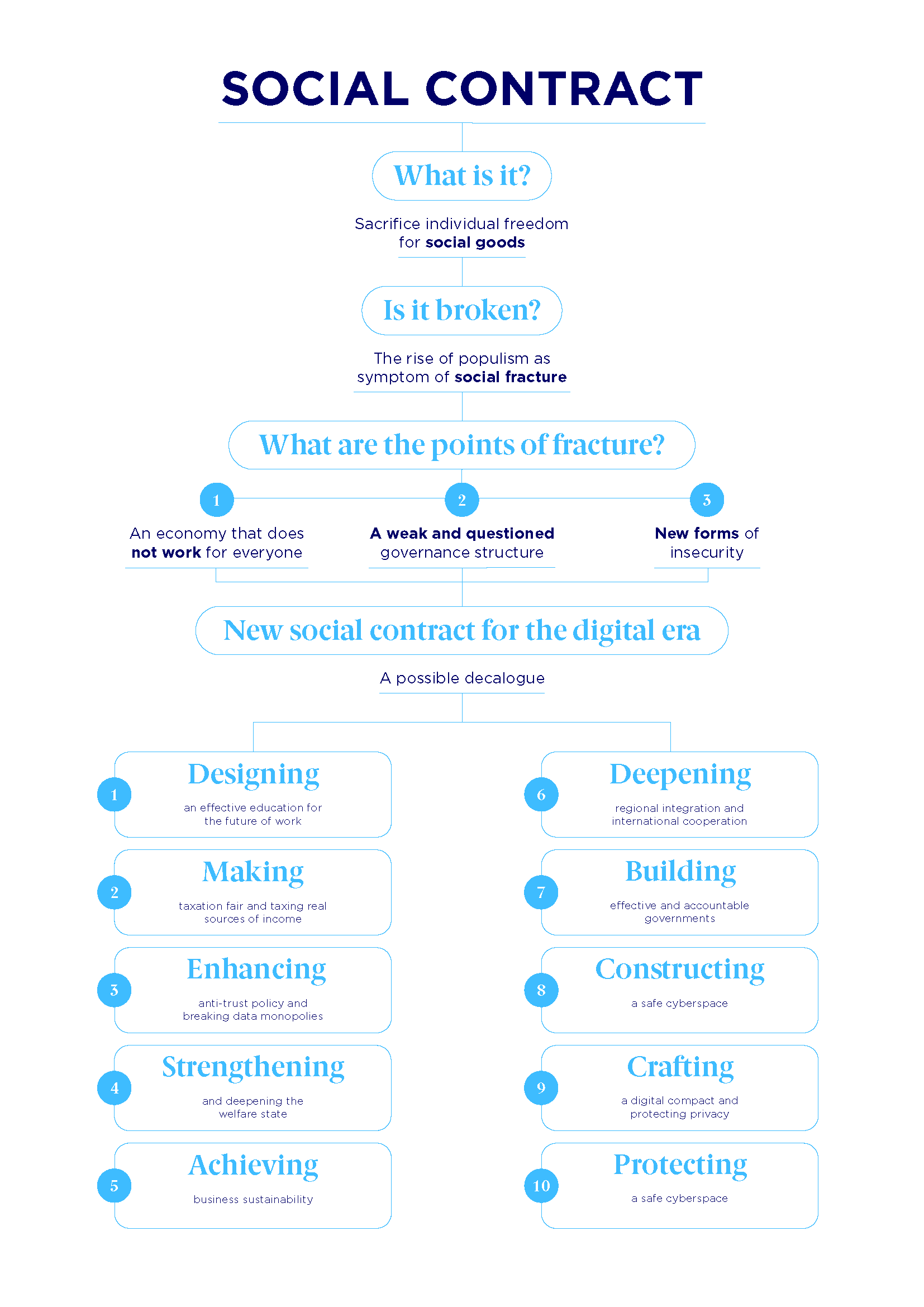

If our current social contract is broken, can it be fixed?

For those of us growing up in Western societies, there were some core beliefs that seemed unquestionable: if you studied and worked hard enough, you would find a decent job and be able to raise a family; economic growth would lead to less, not more social inequality; democracy would give citizens a meaningful say in the political process. The idea of progress held the promise of a future brighter than the past.

But those basic tenets have come under the microscope after failing to deliver for growing numbers of individuals who find themselves financially worse off than their parents, who have lost their jobs to technology or globalization, and who do not feel represented by their leaders. In Europe and North America, many citizens are feeling threatened and left behind by all the fast-paced changes of recent decades, and they are turning to populism for answers.

Some experts see this as a sign that the unwritten rules that bind us together need an urgent update. In other words, the time has come for a new “social contract for the digital era” that will address the deep flaws in our current societies before the fracture becomes too great.

“It could be argued that technological and social transformation has been so deep over the last decades that fundamental features of our social contract have become undone,” writes Manuel Muñiz, Provost at IE University and Dean of the IE School of Global and Public Affairs, in the book Work in the Age of Data.

In his analysis, Muñiz notes that this widespread disillusionment with the existing system is particularly evident in the rise of populist movements, which are questioning essential pillars of Western societies.

“Populists advocate for an agenda that upends decades-old consensus about the role of the state, the importance of diversity, the centrality of trade and open markets in our economy, and, in many ways, the value of democracy itself,” he writes. “This new political landscape is a warning call; one that tells us that there are profound ills within our societies and deep social fractures that need mending.”

In recent years there has been a significant uptick in more extreme political views. In the US, a deeply divisive president held office from 2017 to 2021 and in Spain, an ultranationalist party named Vox is about to enter a regional government for the first time since the country transitioned to democracy in the late 1970s. Political observers are wondering whether this is a sign of things to come elsewhere in Europe.

Social contracts: birth and death

But first, what is a social contract? While there is no clear-cut definition, thinkers from Hobbes to Rousseau have discussed the notion of giving up some individual freedoms in exchange for public services obtained within a larger collective. The system works as long as a majority feels that the norms are fair, and there is a school of thought that sees social contracts as mere vehicles to legitimize pre-existing power structures, since nobody is truly given a choice – or indeed, a contract to sign – when they are born into a society. Social contracts have also been likened to modern constitutions, which can be amended by lawmakers and ratified by citizens.

Muñiz argues that social contracts are not static but “a living concept” that changes with time. He notes that over the last few decades, Western societies have witnessed a significant expansion of the social, economic and political rights encompassed within their contract. “There are economic rights, such as generalized access to health care or education, which are considered fundamental by many Western citizens today but would have constituted truly extravagant propositions at the turn of the 19th century.”

However, there are times when “societies fail to adapt to fundamental changes in their environment and hence their norms become ineffective or obsolete. The fracturing of the social contract that ensues is accompanied by periods of social instability or outright unrest. In some instances, political stability only returns once a new social contract is crafted.”

The Industrial Revolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is a good example of a period of profound changes whose speed was not matched by political reform. “The rise of Fascism and Marxism can, indeed, be understood as symptoms of a dying social contract and of the rigidity of societies unable to accommodate to a new socioeconomic reality,” writes Muñiz. “The convulsion that ensued in the first half of the 20th century could be seen, therefore, as a direct consequence of a poorly crafted social contract.”

Fast forward to the present with its divisive politics, widening economic inequalities and growing social unrest, and the question is inevitable: is our current social contract broken as well? And if so, can it be fixed? Rebuilding citizen trust will be paramount for policymakers, but the task ahead is complex.

Fracture lines

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) noted in a 2019 report that “middle-class households feel left behind and have questioned the benefits of economic globalisation.” In many countries, middle incomes have grown less than the average and in some, not at all. Technology has automated jobs while the cost of goods and services such as housing, which are essential for a middle-class lifestyle, have risen faster than earnings and inflation. “Middle classes have reduced their ability to save and, in some cases, have fallen into debt,” notes the OECD.

Parallel to this, a tiny fraction of the population is amassing wealth like never before. America’s top 10% now averages more than nine times as much income as the bottom 90%, according to UC Berkeley data. Inequality in the US is now at similar levels as the Gilded Age of the early 1900s, according to the Institute for Policy Studies. High inequality also has an impact on health. Muñiz notes that in the US, there are communities where the life expectancy of children is shorter than that of their parents, something unseen since the days of World War II.

And there is a political spillover as well. “This hollowing out of the middle of the income distribution seems to also be producing the hollowing out of the middle of the political spectrum with growing support for extremist parties across the Atlantic,” writes Muñiz. There is an ongoing debate about the drivers of middle-class erosion, but two factors that come up are globalization and technology, which also facilitate corporate tax avoidance and a greater shift of income from labor to capital.

The deepening interdependence between states – with the European Union being a case in point – has also distanced the decision-making process from national forums. Citizens may feel they have no say on relevant issues, and that their national leaders are becoming less accountable. “This sense of loss of political control over one’s own destiny and of the community one inhabits is extremely detrimental to the legitimacy of the social contract,” writes Muñiz.

Another stress vector is a pervading sense of insecurity. One of the ideas behind the social contract is that individuals give up freedoms in exchange for security. But digitalization has created new risks that governments are struggling to deal with, such as cybercrime, privacy breaches and misinformation campaigns aimed at influencing electoral processes. Citizens may feel that their elected leaders are unable to protect them from predatory online actors.

Solutions

Muñiz argues that higher education should be a priority for policymakers because the job market is changing fast and educational institutions must adapt. He notes that despite all the dire predictions about jobs lost to automation, many new occupations are being created and companies are struggling to fill these positions due to a lack of skilled candidates. There is growing demand for workers with high social and quantitative skills, and most particularly digital skills.

Another priority should be fair and effective taxation at a time when there has been a steep rise in tax pressure on labor income and a dramatic decline in tax pressure on capital, notes Muñiz, adding that this is particularly true of internet companies, whose activities are harder to identify, track, and tax. The middle classes are being subjected to greater tax pressure than ever, partly to offset the loss of public revenue from capital earnings.

“This has led to the incongruous situation of collectives that should now be the beneficiaries of redistributive policies being the ones asked to help solve public funding problems or bail out mismanaged banks,” writes Muñiz. Governments will have to find efficient ways to redistribute wealth and may want to experiment with a universal basic income or conditional cash transfers.

Nurturing more competitive markets should be another goal. The digital economy is showing signs of oligopolistic tendencies, and regulators should ensure that the largest companies do not continue on their path of acquiring rivals and stifling competition. On a broader scale, the entire private sector should question its current focus on shareholder profits and commit to positive social and environmental change in order to ensure sustainable long-term growth.

At an even higher level, regional and international cooperation will be more necessary than ever to tackle serious global challenges such as environmental degradation and corporate tax avoidance. The EU, for instance, should keep working towards a monetary, banking and energy union. Existing concerns about transparency and accountability could be significantly reduced through GovTech, technology geared towards improving governance.

Governments must also take action to deal with cybercrime and other forms of digital abuse that create a sense of insecurity, and this will require a new regulatory framework. Social media companies may have to partner with governments to address misinformation and election hacking concerns. Data management will also require new regulation to protect individuals’ data and privacy.

Ultimately, writes Muñiz, “the challenge we face is not one of resources or scarcity but one of managing abundance. [...] We are faced with the task of proving that our social intelligence can match the complexity of the society we have built.”