The fact that millions of people start their day with a nice cup of coffee can be traced back to one of the tariqas (orders) of Sufism, the mystical interpretation of Islam. This reflection, so out of place for a Monday morning, led my thoughts to diversity and entrepreneurship—two aspects of Islam less well known in the West, and probably the ones that most attracted me to the religion.

In today’s world, one feels obliged to take sides, to belong to a bloc, to adopt the discourse of the clash of civilizations. In contradiction to Huntington’s well-known thesis, I would like to argue precisely the opposite.

The origin story of coffee is a good place to start because it is more than a historical curiosity. Indeed, it involves both little-known aspects of Islam that are of enormous interest to me personally.

Islam began with a divine revelation to a merchant in a highly commercial environment that was undergoing an expansion, thanks largely to the great caravan routes. The religion spread into various regions mainly through seduction, despite Western beliefs to the contrary. In my opinion, the success of Islam was probably due to the egalitarian and horizontal discourse of its message, as well as its holistic component, i.e. the fact that it provides safe and effective answers in all aspects of human life.

Few civilizations have managed such great diversity so successfully. This observation opens the mind to a new understanding, different from our current perception of Islam.

A message that is transmitted so successfully and remains unchanged for so many centuries in such a diverse range of regions, peoples, and cultures is clearly inclined to accept diversity. An Arab from Medina has little or nothing in common with a Tajik Muslim, yet both adopt the same creed—a creed that, beyond the spiritual aspect, embodies duties and answers to issues that affect their daily lives, from what they eat to how they handle their finances.

We almost never hear about diversity in Islam, although the religion is obviously very diverse. Indeed, few civilizations have managed such great diversity so successfully. This observation opens the mind to a new understanding, different from our current perception of Islam, which is so often presented as hostile, violent, and insular. We forget that by the end of this century, a third of the world’s population will adhere to this religion and this worldview. And some of this growth will take place in emerging regions with great economic potential, where a large percentage of the population is very young.

There is diversity in Islam; indeed, it has been diverse from the outset. Islam implies tolerance and management of the unknown. The vast majority of my readers will surely dispute this affirmation, but let’s try to reflect for a moment. Is it possible for an idea to spread solely through the imposition of force? I don’t think it’s possible, at least not for very long. The history of Islam proves this: the fact that the religion has adapted to extraordinarily different realities and cultures necessarily means that it has had some degree of success in managing diversity and that pre-Islamic cultures had a high capacity to absorb the religion’s principles.

But let’s return to the journeys of those Sufi Muslims. Imagine those encounters. Enormous caravans leaving Yemen on a pilgrimage to Mecca, bringing customs and discoveries with them. Eventually the Turks would adopt that bitter and energizing new infusion as their own. Such different cultures, sharing knowledge and enriching each other. Diversity and trade.

The pillars of Islamic finance introduce a moral component into human beings’ relationship with the economy.

Entrepreneurship has always been well regarded in Islam. The story of the Prophet himself dignifies trade and good management while condemning usury and speculation. These are some of the pillars of Islamic finance—pillars that introduce a moral component into human beings’ relationship with the economy. Without knowing the origin of these principles, most unprejudiced citizens of any country would accept them without much hesitation.

But it’s not easy nowadays to talk about Islamic finance in the West. The label Islamic conjures up so much noise that it becomes impossible to hear the message or see the messenger clearly. Nevertheless, Islamic finance does exist as such; the industry accounts for about 1% of the world’s financial assets and is growing at a double-digit rate. Still, the interesting thing, in my opinion, is not the success of this industry in today’s post-crisis world, but rather the growth of an approach that is non-speculative, fairer, and grounded in the real economy in an industry as complex as financial services.

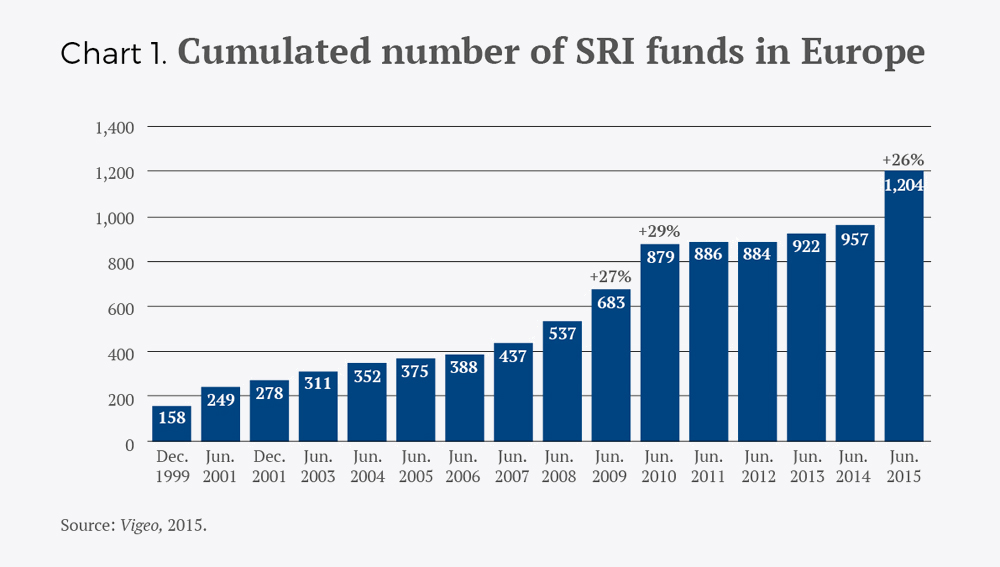

I know from experience that not only is Islamic finance growing, but so is ethical or alternative banking. A large portion of the population clearly feels very disaffected towards traditional banking and many investors are seeking more ethical ways to invest their money. Just look at the number of ethical funds in Europe, which rose from 158 in 1999 to 1,204 in 2015, according to the 2015 Vigeo report.

Especially after the last financial crisis, this public demand for a more ethical, transparent, and responsible form of financial management is itself a clear opportunity to promote a better understanding of a new financial model—Islamic finance—that has a significant moral and ethical component. Personally, I don’t believe that Islamic finance is any more ethical than other forms of finance, or that you must choose one or the other, but the very interesting legal and financial structures offered by Islamic finance are truly surprising to discover.

These structures—with curious names like mudaraba, musharaka, istisna’a, and sukuk—integrate a number of fundamental principles: a prohibition against charging interest, a prohibition against speculation or excessive risk-taking, a connection to the real economy, and equal positions for the lender and borrower.

For the uninitiated, learning about Islamic finance can be fascinating. You discover that simple (or complex) structures such as sales, leases, mortgages, bonds, and project finance have a different, nontraditional structure that breaks with the established model in two fundamental ways: greater equality between the parties and less speculation.

This understanding of finance does not mean, by any means, that one must avoid maximizing earnings or turning a profit. Let’s go back to the genesis of Islam. This is a religion that was revealed to a trader. Trade forms part of its DNA—but not trade at any price. A commercial understanding of Islam is conspicuously lacking, like so many aspects surrounding this worldview and religion.

To establish a clearer and less biased view of Islam, a good starting point would be to celebrate its diversity rather than seeing it as a single monolithic entity.

The same is true of the real situation of women in Islam—in particular, women’s financial autonomy. Few are familiar with the exemplary figure of Khadija, the first wife of the Prophet, who was a successful independent merchant in Mecca. In fact, Muhammad was employed by the clever Khadija for several years. He had no qualms about working under the direction of his future wife, who later became the first Muslim. Khadija was a far cry from the submissive, sad image of Muslim women so often projected in the West. In truth, it is impossible to generalize about Muslim women, given the extraordinary diversity encompassed by Islam.

Western perceptions of Islam tend to be filled with prejudice—an inherent tendency of human beings when confronted with the unknown. But at the very least, we would do well to remember that Islam is not a simple, unitary body, but rather the opposite, and that in this religion we might discover values that are completely unknown in our part of the world. Two such values are the enormous diversity present since the genesis of Islam and the entrepreneurial component of the religion. These values breed attitudes such as creativity, seduction, risk-taking, and innovation.

The representation and understanding of Islam in the West is biased by prejudice and fear of the unknown. To establish a clearer and less biased view of Islam, a good starting point would be to celebrate its diversity rather than seeing it as a single monolithic entity. And one small way of doing this, over your next morning coffee, would be to remember the origins of this universally appreciated drink.

© IE Insights.