Without doubt, Asia is the great success story of recent times. But will that success continue? Or is the deceleration in growth presently observed in many Asian countries a portent of what is to come? Asia is indeed facing a watershed moment. To maintain momentum in its climb up the income ladder, Asian economies face some difficult policy decisions that go far beyond coping with COVID, supply shocks, and their aftermath.

Asia’s development model has so far had two dominant features. One is the way in which governments have used industrial policy to help new sectors and businesses develop. That has been particularly pronounced in South Korea but also in China. Success with such policies has, however, been very mixed. The second – and less well-recognized characteristic – is the common reliance on business groups, a corporate structure that is largely absent in the advanced economies.

What ties these features together are the pervasive and enduring networks of connections that link businesses and politicians. These are present across Asia, irrespective of political system. We term this the Connections World. At the apex of this world sit politicians and political parties along with the mainly family owned – often dynastic – business groups. The latter look to politicians to protect them from competitors, as well as provide them with cheap loans, subsidies and public sector contracts. Politicians look, inter alia, to these business groups to support state-led initiatives and provide jobs in politically sensitive regions, as well as for themselves and their families. The relationships linking politics and business are thus highly transactional, often with a strong element of reciprocity about them.

Business groups are a format ideally suited to the Connections World. From the politicians’ point of view, they provide concentrated points of contact and so reduce complexity in policy making. It is much easier to guide the economy if a significant part of the economy is dominated by a small number of companies. The business groups in turn are organized in ways that allow their owners to respond rapidly to requests and opportunities, not least by permitting them to shift resources around the group, often using transfer pricing or inter-group loans. Their complex structures also act as an effective deterrent against possible predators, whether political or commercial. So, even when one of these groups falls out of favor with its political patrons or falters commercially, few actually fail. Once having found a place in the sun, few get pushed irrevocably into the shade. Thus, while the cast of characters is by no means fixed – new connected companies can and do enter in most contexts – the fact remains that the number of players remains restricted.

As a result, one of the most striking consequences of the Connections World is the accretion of market power by business groups. Not only does their economic firepower allow them to dominate the various markets in which they operate, but it also allows them to achieve significant scale relative to the economy as a whole. A measure of this is the concentration ratio. For example, the revenues of the largest ten businesses – almost all of which are either business groups or state-owned companies – account for around 15% of GDP in India and China and a staggering 40%+ in Vietnam and South Korea. In the latter, Samsung alone accounts for over 20% of GDP. To put this in context, the comparable share for the ten largest companies in the US is around 4%.

The Connections World is turning from being a driver to a potential drag on Asian growth and development.

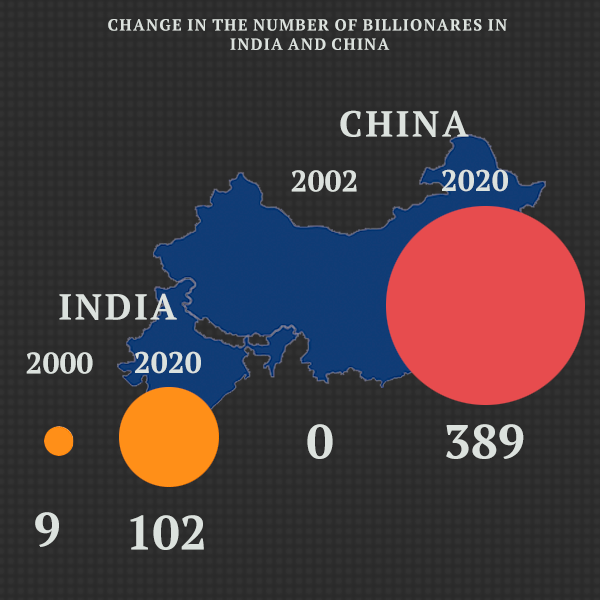

The striking way in which business groups have come to occupy so much economic territory is matched by the parallel accumulation and concentration of wealth, as well as the speed with which this has occurred. In China, the number of billionaires – again almost all of whom are owners of businesses – catapulted from 0 in 2002 to 42 in 2008 to 389 in 2020. Their median wealth also grew from $1.5 to $2.1 billion between 2008-2020. In India, the number went from 9 to 102 between 2000-2020. And large increases have occurred right throughout Asia.

Even though the Connections World concentrates benefits, it has, for the most part, supported Asia’s extraordinary growth over the past half century. But problems with this model, and the configuration of economic and political power that it has enabled, are mounting. On one plane, Asia’s demographics are increasingly challenging its extensive growth model that has been based primarily on increasing applications of capital and labor. At the same time, the attenuation of competition that comes with having privileged business groups at its core holds back productivity growth, as well as limiting the number of high-quality jobs. Yet, perhaps the most significant challenge is that the Connections World stands in the way of Asia shifting to greater reliance on innovation. While some of the business groups are undoubtedly highly innovative – Samsung is a clear case in point – many are not. And, as importantly, the universe of companies having adequate access to the resources – financial and manpower – necessary for innovation remains very limited. Moreover, the politician-business nexus impedes improvement in institutions and sustains the sort of venal and undesirable relationships that have frequently been exposed, not least in Sri Lanka’s recent meltdown.

In short, the Connections World is turning from being a driver to a potential drag on Asian growth and development. Even so, it clearly will not disappear of its own accord because all the important players in the game gain from its continuation. The losers are the businesses and entrepreneurs unable to compete with business groups along with workers unable to get ‘good’ jobs. A shift in the balance in the latter’s favor will require policies to accelerate the disappearance or, more likely, the transformation of business groups. The United States addressed the problem of business groups under Roosevelt in the 1930s by prohibiting pyramids and related party transactions while enhancing the protection of minority shareholders. The impact was boosted by the application of strict competition policy, including explicitly targeting business groups. This may be hard to replicate in Asia given entrenched interests and the power that they hold. More promising is likely to be the use of additional tax instruments that are conditioned on the ownership format and hence target business groups. This involves levying additional taxes on businesses that choose to be organized as business groups. And South Korea has introduced a high inheritance tax, one aim of which is to limit family control across generations. The evidence so far suggests that this is likely to be an effective instrument and one that has the additional virtue of helping address the very high wealth inequality that exists throughout Asia.

Complementary to these approaches are measures to promote competition. Israel, for instance, has adopted a slew of policies aimed at restraining market power not just at the level of a sector but also at the level of the economy. Then, there is the need to limit the scope for politicians to leverage their business connections. That rests on greater transparency and the strengthening of civil society, including the application of asset and interest declarations for politicians and more stringent penalties for breaches. As experience throughout Asia illustrates, this is by no means easy to achieve.

To conclude: Asia’s further climb up the income ladder has nothing automatic about it. Indeed, a failure to come to grips with the Connections World will impair the brightness of its future.

© IE Insights.