“If you are not pissing off 50% of the people, you are not trying hard enough,” Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, famously said nearly 20 years ago. And the quote could perfectly summarize the philosophy, known as brand activism, that is driving many CMOs of American and European brands today to take a stance on divisive social and political issues.

Brand activism is sometimes confused with corporate social responsibility (CSR) or sustainability, but what distinguishes these concepts is the partisan quality of the cause. CSR tends to embrace causes with a low level of polarization (for example, education, health), while brand activism tends to favor highly polarizing issues (for example, gun control, transgender rights).

There is no shortage of examples of brand activism – Patagonia, Ben & Jerry’s and Nike have historically engaged in social and political activism – but as we witness more brands embracing activism, the position taken by the public, from business leaders and academics to voters and consumers, on the need for brands to take a stance has become more divergent.

According to the 2020 CMO Survey, run by Christine Moorman of Duke University who has been long studying brand activism, less than a third of marketing leaders agree that using marketing communications to speak out on political issues was appropriate for their brands. But nevertheless, they feel pressured to take a stance. The Financial Times’ “Moral Money” section, which is focused on sustainable business and finance, asked its readers (mostly executives in big global organizations) if they felt pressured for their organizations to take a stance, more than 60% agreed with the statement and only 4% disagreed. The rest thought that a firm should only take a stand if the issue is clearly related with the company’s business. But this contrasted with the view of consumers and voters, who are less likely than marketing executives to agree with the political positioning of brands.

Even among executives, some warn of the perils of taking a stance. Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, and a proponent of stakeholder capitalism, wrote in his 2022 letter to shareholders: “Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not “woke” (…) The stakeholders your company relies upon to deliver profits for shareholders (…) don’t want to hear us, as CEOs, opine on every issue of the day, but they do need to know where we stand on the societal issues intrinsic to our companies’ long-term success.”

When taking a stand on a divisive issue, a big brand is more likely to churn more clients than it will attract.

In fact, positioning around politics carries risks when it comes to consumers’ reactions. Recently, Bud Light faced a backlash after transgender activist and influencer Dylan Mulvaney posted an Instagram promotional video showing a commemorative can of the beer with their image on it. This prompted a consumer boycott which negatively impacted sales, which declined more than 20% in April, compared to the same period last year according to some sources. In turn, this has led to strained relationships with distributors. Not only that, but a full-blown crisis born out of “one can, one post, one influencer.”

On May 4, during the first quarter results announcement call, the AB Inbev global CEO, Michel Doukeris, acknowledged that there was evidence that the Bud Light crisis had a spillover effect on other brands in the portfolio. During the same call, he announced significant budget and organizational changes including that media investment for Bud Light would be tripled for the summer and the marketing team would be restructured, letting go of the marketer responsible for the campaign and involving more senior marketing executives in relevant brand-related decisions.

However, once these measures were announced, Bud Light was faced with another boycott from “LGTBQ+” bars who now refused to stock the brand. Bud Light was a brand between two fires.

Doukeris explained that the company’s key learning from this crisis is that the brand should avoid being the focus of this kind of debate and avoid being pulled into such discussions. Brendan Whitworth, CEO of Anheuser-Busch US explained that Bud Light “never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people” and Bud Light is “in the business of bringing people together over a beer.”

If you are a leading brand in any given category, chances are your customer base is likely to be equally divided among people that oppose or support a particular political position. This means that activism is a riskier business for large share brands, according to research from Chris Hydock of Orfalea College of Business with Neeru Paharia and Sean Blair of McDonough School of Business. They present a hypothetical case for a brand with a 90% share that takes a political stance on a divisive matter and assume that support and opposition is evenly split, with those who oppose it reacting twice as strongly than those who support it. They find that after a brand takes such political stand, it is likely to lose around half of those customers who oppose its stance (22.5%) and only attract a quarter of the uncaptured market (2.5% extra share.)

The significance is that when taking a stand on a divisive issue, a big brand is more likely to churn more clients than it will attract. Why? Because immediate consumer reactions are stronger in case of misalignment. The situation is different, however, for smaller share brands, which are more likely to benefit from activism if the market perceives it as an authentic stance.

This is exactly what happened to Bud Light, a US brand valued at $5.949B by Brand Finance. Its customer base was alienated and given its leading position, there was little to gain from taking that stance. Yet, there were other brands that partnered with Dylan Mulvaney around the same time as Bud Light, such as Maybelline and Nike, and these brands seemed to have come out the other side of the tunnel unscathed. Some analysts attributed the difference to customer base profiles: Bud Light is composed mostly of conservative men. But there is another factor that could explain the Bud Light debacle. Very recently, Nike’s decision to collaborate with Dylan Mulvaney to promote its female sports clothing range has sparked outrage, although to a lesser degree than the vitriol aimed at Bud Light. This is because, unlike Bud Light, Nike has a history of getting involved in social and political issues and has not reversed the course of its decision.

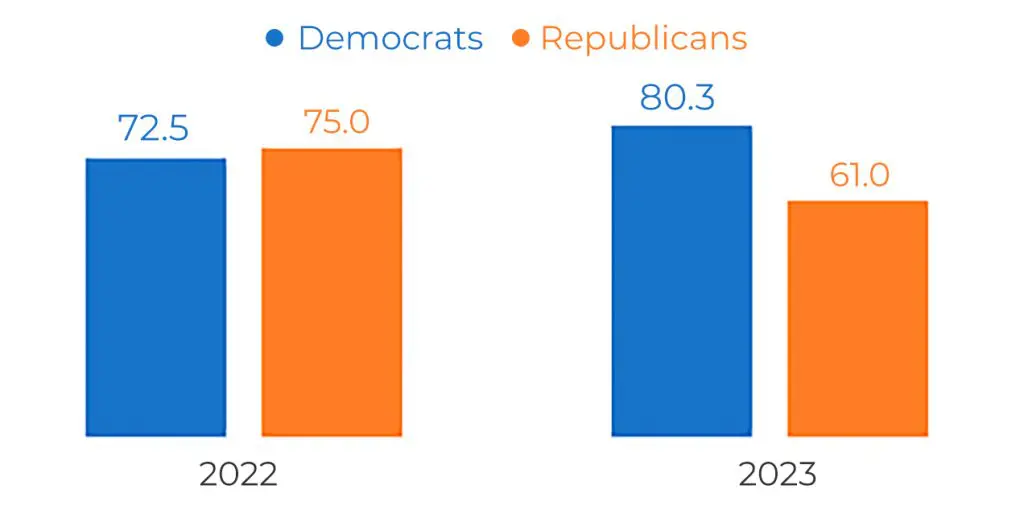

The results of the 2023 Axios Harris Poll 100, which measures the reputation of the most well-known US brands among 16,000 Americans, help illustrate how taking a political stance can significantly affect the reputation of a corporation when the general population hold heterogenous views towards it. For example, after taking a stand on DeSantis’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, Disney’s reputation improved among Democrats (from 72.5 in 2022 to 80 in 2023) but significantly worsened among Republicans (from 75 in 2022 to 61 in 2023). On balance, the reputation of Disney declined from 73.4 in 2022 to 70.9 in 2023, losing twelve positions in the ranking of most reputed brands. “Divide and conquer” becomes “divide and succumb” when it comes to brand activism.

Disney’s Reputational Quotient

Source: Made by author based on the results from Axios Harris Poll 100, 2023

In addition to consumers, brand activism also affects corporate audiences, and in particular shareholders. According to research from Yashoda Bhagwat of Texas Christian University and Nooshin Warren of the University of Arizona, with colleagues, “given its partisan quality, (…), activism raises the level of risk and uncertainty beyond traditional CSR activities.” They found that activism actually decreases the value of the company by increasing its risk profile because shareholders view activism as a sign of a misallocation of resources that distracts company executives from core operations. The sheer number of questions asked by analysts and explanations given by the AB Inbev CEO in their latest results announcement call, illustrate how activism can affect analysts’ and shareholders’ perceptions.

Four key learnings from this case that every CMO should consider before embarking on brand activism:

- At a consumer level, larger brands have more at stake when taking a stand than smaller brands.

- The more politically heterogeneous the customer base might be, and this tends to be the case for large brands, the higher the risk posed by activism.

- The effect of taking a stand is mediated by perceived authenticity and the history of the brand.

- Shareholders view activism as an inefficient allocation of resources that increases the risk of the firm and therefore, diminishes value.

Among business executives and academics, there is a growing clamor of critical voices against brand activism. Social, environmental, and political issues are too complex to be binary. The big question for brand managers – particularly those of big brands – is whether their activism will underline the social divide or impact their community with concrete, relevant, and measurable initiatives. What is the most effective way of bringing about positive change? At this point there does not seem to be a definitive answer, but we should keep hope that companies and brands will find a way to bring society together.

© IE Insights.