Main image: Um ano do paço, Juan Cabello Arribas

O Brasil não é para principiantes. Legendary Brazilian musician Antonio Carlos (Tom) Jobim’s phrase, which has turned into a mantra for the country – particularly so in the age of the Internet – has only become more true with time. Brazil is not for beginners.

It’s not easy to understand the events of Sunday, January 8 2023 in the Brazilian capital, but perhaps it is possible to see them as a global phenomenon with local nuances that are characteristic of a society still governed by the ideals of “order and progress” inscribed on its colorful flag. This flag reflects part of Brazil’s history, the part the country has sought to preserve and the part that there may still be time to rewrite. The green and yellow of the Brazilian flag as we know it today are references to the imperial flag and the Houses of Bragança and Habsburg, coming from its first Emperor and Empress Peter I and Maria Leopoldina. The blue circle and the 27 white stars, which stand for the 27 Brazilian states, represent the sky that had stretched over Rio de Janeiro, then the capital, just a few days before the empire fell and a “new Brazil” was introduced to the world in 1889. The words Ordem e Progresso (Order and Progress) are inspired by Auguste Comte’s positivism Love as a principle, order as the basis, and progress as the goal, and were intended to kick off the construction of the institutional framework – the social and political structure – of what we know today as Brazil.

A year before these starry skies, green fields, and golden diamonds, Dona Isabel, the Princess Imperial Regent of Brazil nicknamed the Redemptress, signed the Golden Law and abolished slavery in Brazil. However, as is evident by the current condition of the country, this valuable document stayed in the realm of ideals and utopias that built, and still builds, what Brazilians acclaim as the “Country of the Future”.

The seeming freedom of the Golden Law and the poetry of the country flag are reflected in what happened recently in the Brazilian capital, a representation of the past’s unequal history, written by emperors and empresses, and the current machinations of a few orchestrators committed to destabilizing the democratic foundations of the “young” country.

Alongside all of this power, throughout history, there have always been architects, artists, designers, poets, and musicians spurred on by the vital energy of building a new country together. The case of Brasilia is yet another example of the fragility of the approaches taken by these groups of experts who, possibly bewitched by the beauty of their arts and ensnared by the elixir of their essences, forgot the significance of society as a participatory and active player in building democracy.

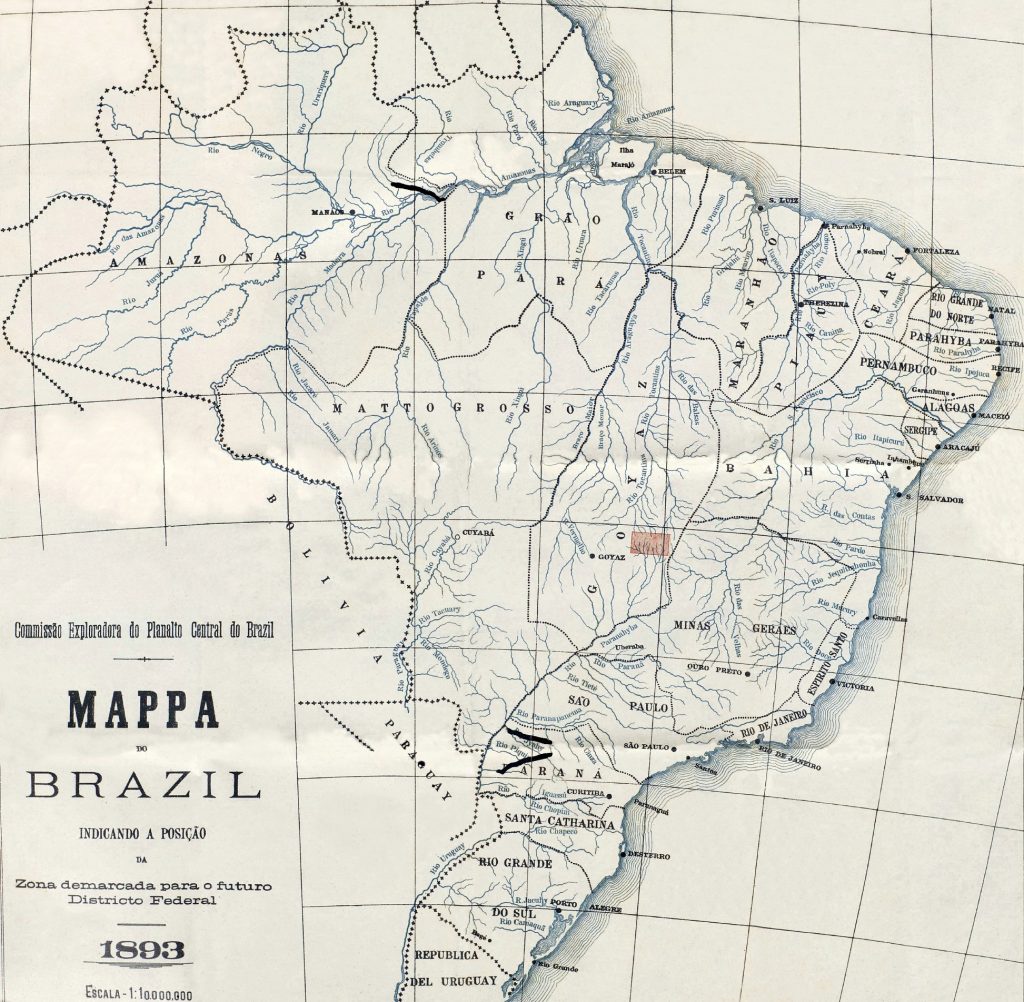

In the late 19th century, President Florencio Peixoto’s administration felt the pressing need to isolate the nation’s ruling power from its people and, in 1893, the “Cruls Rectangle” appeared in the center of the map of Brazil, marking the site of the future Federal District which would then become Brasilia. It was precisely at this time, at the theoretical establishment of democracy, when the first anti-democratic attack took place: the planned separation of governors and the governed in the territory.

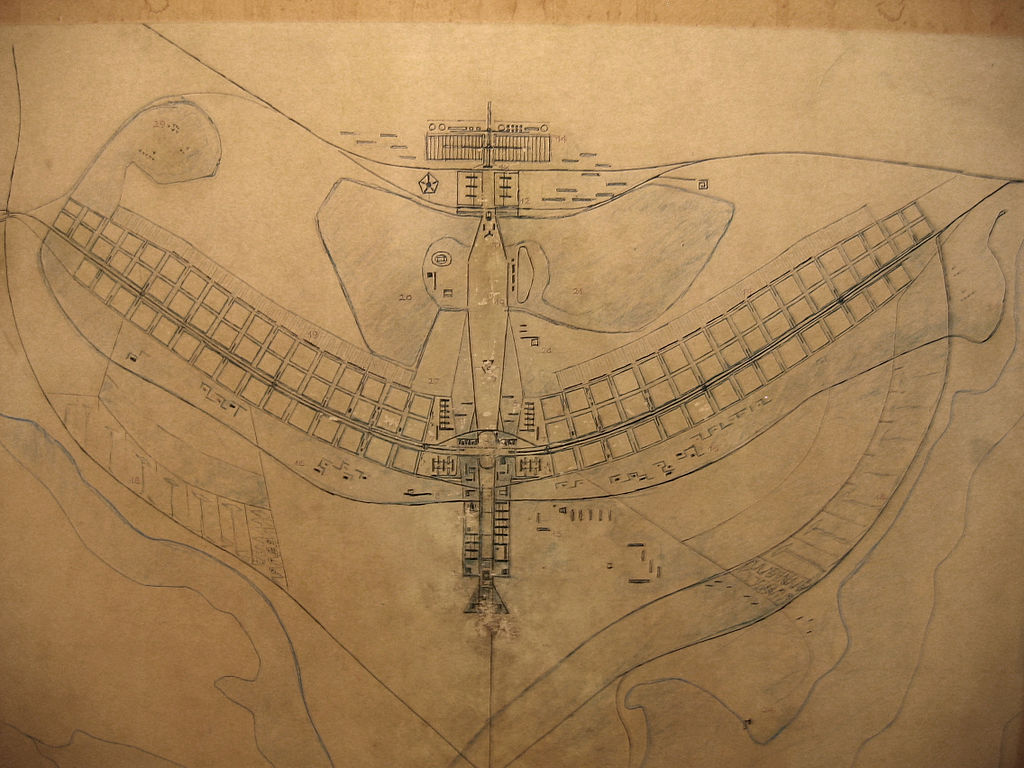

Map of Brazil from 1893 showing the “Cruls Rectangle”, the future site of Brasilia.

In the tradition of the Brazilian Exploratory Commissions, the Cruls Rectangle (measuring 160 km by 90 km) was at the meeting point of the headwaters of the main river basins, thereby securing the essential asset: water.

Political and administrative isolation, assured water supply, and contrived social distance were the cornerstones of this fragile democratic paraphernalia. However, the plans by Lúcio Costa and the buildings of Oscar Niemeyer rested poetically on these foundations, Costa and Niemeyer had overlooked a key social aspect of their construction: the efforts of the people stolen from Africa and their neglect, which continues to this day, after the notional freedom afforded in 1888.

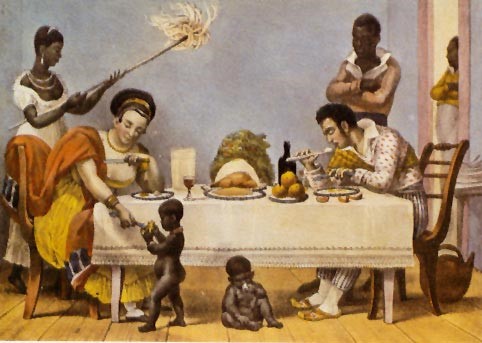

Let us consider three pictures that show how Brazilian society was constructed, evangelized, and stripped of its rights from its origins.

A Brazilian Dinner, Jean-Baptiste Debret, 1827.

A Brazilian Dinner by court painter Jean-Baptiste Debret reflects the Empire’s social segregation. The echoes of this scene created in this 1827 painting can be found in Anna Muylaert’s 2015 film The Second Mother. Through the main character, Val, a maid from the northeastern state of Pernambuco, the movie depicts the country’s issues of social class inequality and the lack of freedom of the “help,” their mistreatment and exploitation – while simultaneously capturing the Brazilian people’s energy and hope for democracy that was unleashed when Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (a Pernambuco native) came to power in 2003. This sentiment was kept alive by his successor Dilma Rousseff, who governed the country from 2011 until the coup d’état via her impeachment on 14 October 2016. For the elites, it seemed that democracy was going too far. The privileges of one part of society had begun to crumble while the poorest attended state university and reached professional positions.

I was there in Brazil on October 14. I watched as the Brazilian people, once more stripped of their freedom, found enjoyment on the beach playing football as if it were a regular Sunday morning. But no, on this day, away from the beach, at the stunning hall of Brazil’s National Congress designed by Niemeyer in the late 1950s was the scene of a consensual coup d’état. Of course, the country’s leader was considered “democratically” ousted and the power of the people, wrested from them by the “same lot” once more, was back on the table of inequality, back to the portrayal by Debret.

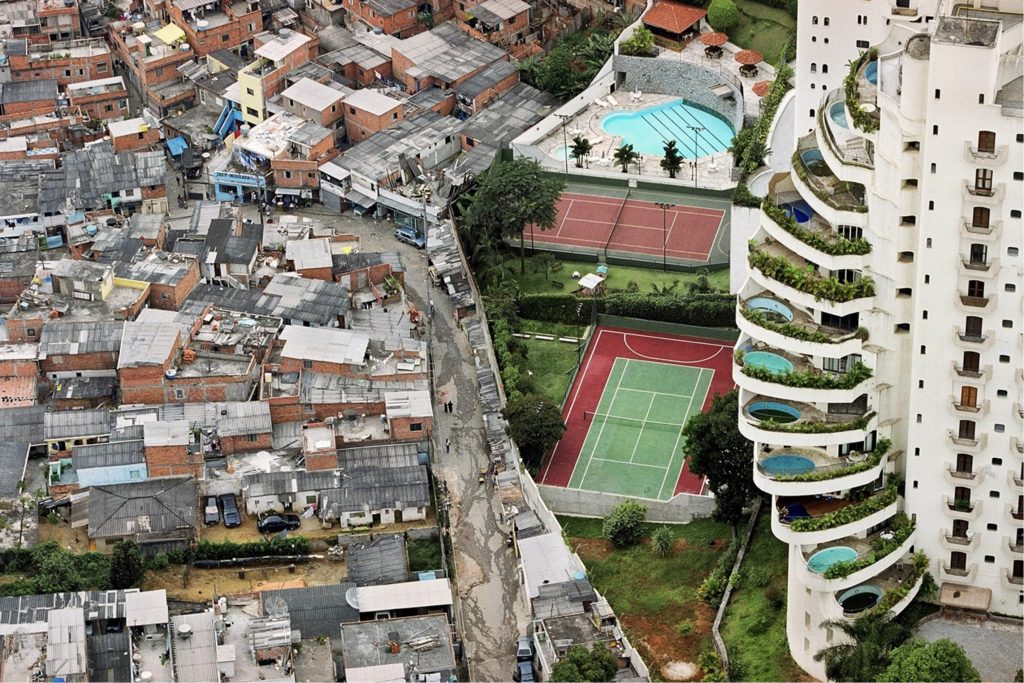

Paraisópolis, Tuca Vieira, 2004.

Eighteen years ago, photojournalist Tuca Vieira took a photograph that has since become a global icon of inequality. From a helicopter over São Paulo’s main ring-road, Vieira captured the stark difference between the Paraisópolis favela and the Morumbí neighborhood, split by the Tieté-Pinheiros waterway. It is a literal wall erected within society. Two worlds. On one side, architecture without architects, resource poverty, disaster, and a lack of public space, that main component of democratic cities. On the other, luxury, plentiful space, and a sense of community.

It has been well documented how the small bars and shops that pepper the informality of the favelas, press up against the city’s private walls. Another formative part of this urban tapestry is the multi-polar system of religious sites and the huge evangelical monuments that double as cultural centers and public spaces for this group of society. Here, the gospels enter where neither the state nor its “democratic preaching” can reach. Architecture is once again a backdrop for democratic reflection. Brasilia cannot be understood otherwise.

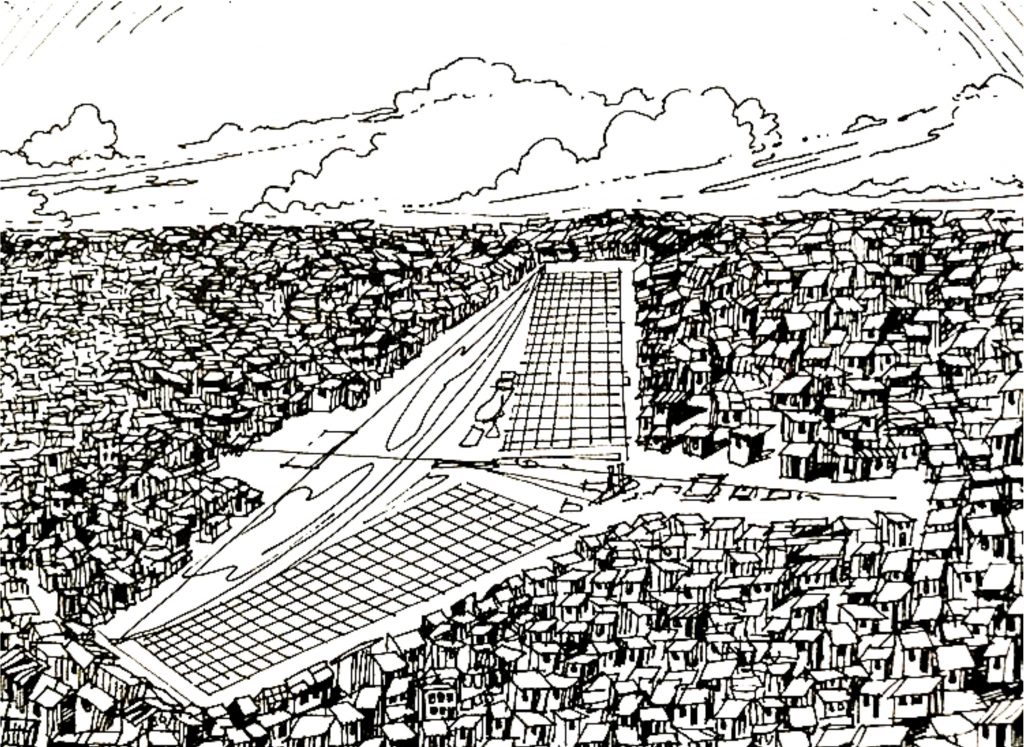

Caricature of Brasilia, Projeto magazine, 1982.

The 1982 caricature of Brasilia, first published in the magazine Projeto, one of the main platforms for critiquing and publicizing Brazilian architecture in the 1980s and 1990s could not be more contemporary today.

Lúcio Costa’s and Oscar Niemeyer’s designs barely hinted at what the nation’s capital would become in the future – and this is, in fact, where their ideal is realized and follows the handbook, step by step, for building utopia: geographical and social isolation (an island), denying the reality that is. Costa and Niemeyer created a Brasilia in the dry climate of the “cerrado,” the open pastureland of inland Brazil with patches of stunted vegetation. It was an isolated dream of immense beauty built in the wake of an imperialist, colonialist, and evangelist past. It preserved the living patterns of a divided, segregated, slaveholding society via the walls of a beautiful white concrete fortress. Brasilia was developed from modern plans drawn from other social realities, and anchored in other popular traditions.

The phenomenon of Brasilia is not an isolated case in the history of 20th-century architecture. Rather, it is just one more of those led by governmental power and “its” architects. Chandigarh, the new capital of the Punjab, developed by modernist hero Le Corbusier, Louis Isadore Khan’s National Assembly Building in modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian Institute of Management complex in Ahmedabad, are other prominent examples of utopian metropoles built in the same era.

The Brasilia Pilot Plan was the outcome of a public competition won by the team of Rio de Janeiro architect Lúcio Costa, born in Toulon in France. His approach, which maintained the static democratic rules of Modern Zoning, contrasted with the paradigm shift being put forward by Europe’s post-war architects at the International Congresses of Modern Architecture, the renowned CIAM, during the 1950s. The modern heroes had to survive; their architecture too. It had taken them a long time to find their place. Democracy was by now a worn-out, stagnant ideal which continued to serve as an alibi for action for the old modern architects.

Pilot Plan for Brasilia, Lúcio Costa

In the late 1950s, the spectacle of Brasilia brought many photographers from the then capital Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo to inland Brazil to shoot the rise of the new monuments.

The pictures taken by French photographer Marcel Gautherot during the construction of the National Congress Building in 1959 show the construction machine running at full steam, using cheap labor shipped in from the north of the country which, albeit not highly skilled, was both inexpensive and hard-working.

These stunning photos capture the naked skeletons of the Congress building’s towers amidst the haze of the dry dust of the “cerrado” and the meticulous work of the laborers in the construction of its domes.

“Order and Progress” towards the construction of a new utopia replete with “beauty” and modern dreams.

National Congress building under construction (left), Chamber of Deputies dome under construction (right), Marcel Gautherot, c.1959. © Moreira Salles Institute Archive.

Yet even more striking and true to life are the pictures by Thomaz Farkas, another of the photographers who went to the heart of the capital to immortalize the events. His photos reveal the failure of a democracy which had only just been founded.

On the other side of the wall, families brought from the north and northeast of the country were settling down and starting to build the other face of Brasilia. New structures in wood and sheet metal were already crowding against each other to build the informality of the new “Brasiliense” society.

These new neighborhood units were as Brazilian as the ones they were building with their own hands following the architects’ guidelines, though lacking in monuments, modular housing, roads, and facilities.

Núcleo Bandeirante, Thomaz Farkas, 1960. © Moreira Salles Institute Archive.

The beauty of the reflecting pools and water gardens designed by Roberto Burle Marx were far from the “Núcleo Bandeirante” administrative region being built next door. The reflections and colors of the tiles dreamed up by artist Athos Bulcão did not cover the kitchens of the flimsy structures. Nor did works by Di Cavalcanti and Cándido Portinari decorate their interiors. Instead, a society was already emerging, one which had survived an unequal past, which saw the power of the Evangelical Church grow in its informal centers, meeting precisely where the state did not reach to set up its community venues.

A new capital was being built out of inequality and neglect, out of the lack of culture and knowledge which existed side-by-side with the illiteracy and religious fervor that continued to grow on the other side of the invisible democratic wall.

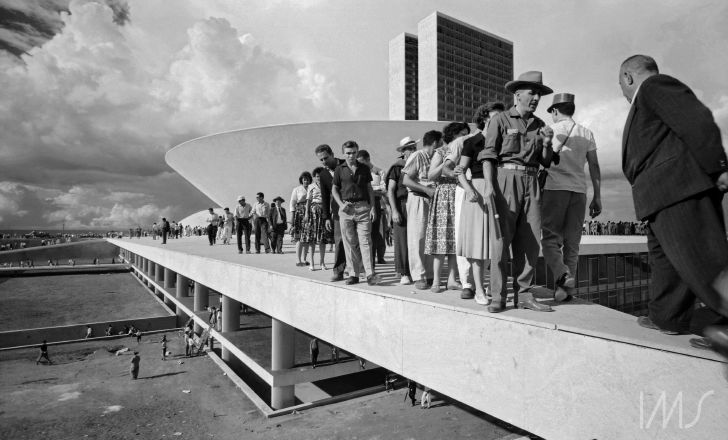

The majority of those who attended the opening of the new symbol of the Brazilian capital on 21 April 1960 were very different from the people who had built it. Yet, in an almost heroic act, Kubitschek and his architects welcomed some of the new city’s residents from across the invisible wall to the great event which would shape the future of Brazilian democracy.

“The people on the roof of the National Congress building on the day of Brasilia’s opening, 21 April 1960”, Thomaz Farkas, 1960.

© Moreira Salles Institute Archive.

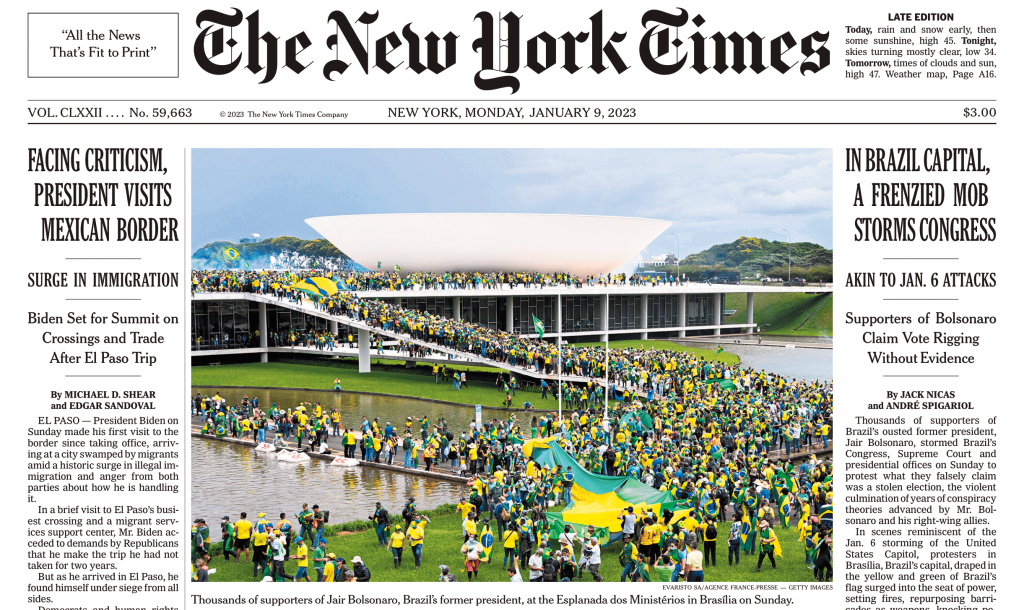

The pictures from the Federal Capital which surprised us on January 8 and shocked the world are not so different to the images of the city’s inauguration.

Yet it is not destruction that shocked but the symbol of the architecture, its undeniable beauty, and the quality of the artworks inside that architecture. The images that hit the front pages in January starkly reveal – in the same way that the images by Debret, Vieira, and of Projecto do – the divergence between the symbols and architecture and the social reality of the current state of democracy.

New York Times cover, January 9, 2023.

Sixty-three years separate the photos of Brasilia’s opening and the chaotic scenes of January 8. The latter shows the two symbols which shaped the country’s democracy: the new flag of green landscapes and yellow-golden diamonds and the heroic beauty of Costa and Niemeyer’s modern utopia. The symbols remain but the values change.

In Bruno Barreto’s movie Reaching for the Moon, Elizabeth Bishop suggests “the longer you stay in a place, the less you understand it.” The more we look at the images of January 8, the less we understand what is going on.

However, what is clear is that Jair Bolsonaro’s anti-system movement should not be taken as an isolated event, no more than should the construction of the new utopias of Chandigarh, Bangladesh, or of the next utopian ideal of Brasilia.

Democracy today, or at least as it is understood, displays all its vulnerability in an invisible world map of erupting volcanoes, shows us that it is flagging in the face of the energy of social media, the power of ignorance, nationalism, religious dogmas, and social segregation.

El País recently revealed that only 42% of the countries in the globalized world have what we consider as freedom in its fullest sense. The other 58% run on different principles, far from the democratic dream. Of course, this is not a new development but, rather, the outcome of a deliberate process, strategically thought out, organized, and connected around the world. Social media, fake news, and new communication platforms are perverting precisely what they represent: communication.

Today’s world has succumbed to the speed of virtual gigabytes. As contemporary cities start to host huge windowless constructions or high-speed traffic hubs, we are forced to leap from the information society to the opinion society under the rules of today’s aggressive freedom of speech. Far from experiencing the thinking and self-criticism intrinsic to discussion and communication, it sees democracy collapsing and hard-won ideals melting away. Yet the world continues to play soccer every Sunday.

The book Utopia Thomas More published in 1551 accompanied the era of the “discoveries” of the great transcontinental exploits, of the construction of “New Worlds.”

Architectural modernism pursued and still draws on these ideals, whether naively or not, with a craving for beauty or not, choosing the path of escape as the alienated solution to contemporary problems.

The need for beauty is undeniable, just as it was present in the lines of Costa, the shapes of Niemeyer, and the gardens of Burle Marx. Yet, today it is also undeniably missing. Perhaps what our present lacks is a new awareness that can grasp the gravity and beauty of new events in a more complex way.

Maybe it is because of all this that we once again feel the need to resume dialogue. We need to implement not only a discipline between disciplines, grounded in dialogue and mediation between different living beings and diverse communities in different geographies and at different latitudes, but also a society based on mediation, on the divergence of standpoints and the diversity of realities which share the same boat.

Neither building monuments nor destroying them will ever be able to shift the world’s democracies towards the much-needed mediation society. Looking at these events alone and thinking together constructively will push architects towards a new architecture of mediation.

Perhaps we should view today’s global map as a geographical system of erupting volcanoes where democracy is steadily losing its values and where architecture is still a visible reflection of their absence.

© IE Insights.