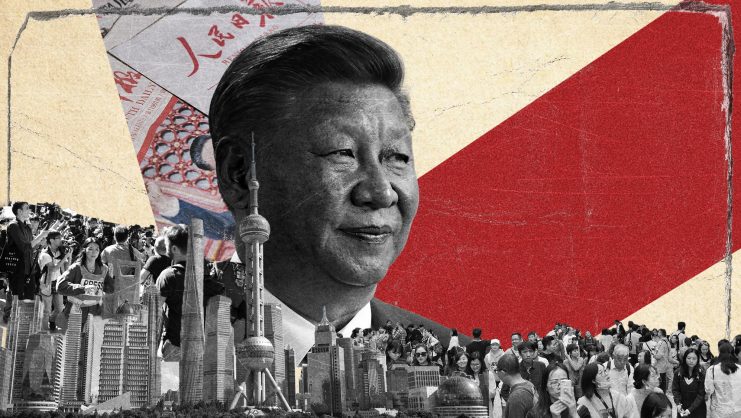

According to Joseph S. Nye, there are three elements that are essential for a nation’s ability to use soft power in order to shape the preferences of other nations. First comes “the attractiveness of a country’s culture,” then political ideals and, finally, policies. These three concepts are used to “lead by example” and “to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments.” Nye focused on the attractiveness of a nation’s brand, its values, ideas, and norms.

Nye’s idea of soft power was introduced in China in 1992 by He Xiaodong who first translated Nye’s book Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. His text was followed, in 1993, by an article by Wang Huning, now a member of the standing committee of the politburo and principal ideologue of Xi Jinping’s government, entitled “Culture as National Power: Soft Power.” Ever since, China has worked hard, with different degrees of success, to imitate the US in its exertion of soft power. But in recent years, China’s aggressive Wolf-Warrior diplomacy, harsh censorship, human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and its military actions over Taiwan and the South China Sea, have largely eroded its former international projection of a benign and generous nation with a policy of non-alignment.

Yes, the list of problems created by China’s image-building under Xi is very long and for the time being, China seems to have lost its brand name with its international image reaching an all-time low. While some argue that this has bolstered nationalism in China and among the Chinese diaspora, it is equally possible that its long-term success in gaining international respect hinges on its soft power: in generating some form of “inducement and attraction” and on commanding respect both in the West and in developing nations. China must convince the international community that its system is as attractive as the one that came out of the US in the aftermath of World War II, though admittedly, this prototype has since lost its luster.

Long before the term “soft power” came into vogue, culture served as a tool for public diplomacy, and has been tightly tied to and funded by governments in the form of university grants, academic exchanges, international conferences, and cultural foundations like the Alliance Française. The aim of most of these institutional exchanges is to establish a focal point of dialogue between countries and cultures. But not all cultural propagation is initiated by governments; there are innumerable non-governmental paths propelled by a country’s own set of cultural values and practices which range from high culture to popular culture and mass entertainment. I have been trying to think of one recent internationally famous cultural phenomenon that stems organically from mainland China—a movie, a novel, a trendy new food—but I cannot think of one. Yes, there is a US-China neck-to-neck race on video games, but I am not sure what is the strong cultural component here. And yes, there is Liu Cixin’s science fiction novel The Three Bodies, but most of his work has been sold in China with just one and a half million copies abroad. Granted, the soon-to-be-released Netflix adaptation of Liu’s trilogy may help international book sales, but still, compare those current sales with that of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, which has sold a whopping five hundred million books worldwide.

There is, however, one interesting and successful example of cultural soft power that originated in China in the 1930’s: Mei Lanfang’s (1894-1961) tour of Japan, the US, and the Soviet Union. The Mei Lanfang example illustrates the complex dynamics of soft power, and provides an interesting glimpse into China’s past exertion of soft power. Mei was a Peking Opera actor who specialized in the performance of highly stylized female roles called dan. Traditional Chinese theater uses a system of roles to determine the skills (voice, gestures) any character needs to use in the performance of a play. So actors, whether male or female, can specialize in any role system, playing either male or female, and it is not unusual for male actors to specialize in female roles and play female characters. By Mei’s time, the performance of female roles had become highly stylized, aestheticized, and skilled, and Mei was one of the most outstanding representatives of the genre.

Mei Lanfang visiting New York. (Photo by © Bettmann/CORBIS/Bettmann Archive)

Mei’s life spanned a period of great political turmoil and rapid change, a time that included the fall of imperial China, Western encroachment and intimidation, Japanese colonialism and the Sino-Japanese war, and the triumph of the Maoist Revolution. It was also a period of great intellectual effervescence when China began questioning its ancient intellectual foundations, searching and experimenting with new modes of government, and considering how to strengthen its political and military position in the world. In its search for status and power, China longed to become an active participant in a highly connected world, and culture was at the heart of this enterprise. Many intellectuals at the time believed that one of the main hurdles China had to surmount in its quest to modernize was the restraints imposed by Confucianism, with its strict social order and demanding cultural values. In the early part of the 20th century, some of the traditional ideas that held family structures together, such as the total authority of the parents over their children, or women’s lack of the most basic rights, began to be rejected. A search to change the political order was also afoot, as well as a reform of its outdated examination system as a means of access to the office.

Among the many considerations for reform, foremost in the discussions was the question of how to modernize popular arts and literature (mainly the theater and the novel) and turn them into a medium of national reform. Traditionally, intellectuals in China had spurned popular literature because of its tendency to misconstrue reality and to elevate outlaws into unethical heroes. Peking Opera too, though widely popular with the urban growing middle classes, was dismissed by important reformers like Hu Shih (1891-1962) and Fu Ssu-nian (1896-1950) who thought of traditional theater as anchored in outdated Confucian values, and burdened by acting conventions such as face paint, elaborate and heavy clothing, acrobatics, and a music and rhythm that were difficult to follow. What the Chinese intelligentsia wanted was a reformed theater, one that would emphasize national heroes and reflect contemporary social problems. But because both the novel and theater were popular forms of entertainment with wide-reaching audiences, these genres were seen as useful means of ideological dissemination and excellent didactic vehicles for social reform.

It was not enough, however, to reform culture within China. Intellectuals also needed an artform that was respectable, refined, and representative of its long civilization, and that could be situated on the world stage as uniquely and essentially Chinese. So, what art was there to export? Intellectuals settled on Peking Opera as the best showcase of China’s unique culture, despite all of the reformer’s objections to traditional Chinese theater.

Instrumental in this decision was Qi Rushan (1877-1962), a well-educated scholar and playwright with a profound interest in the theater. Qi had traveled to Paris on various occasions and was intrigued by the importance French society attached to theater and opera not only as the preferred form of entertainment, but also as a means of intellectual discourse. In spite of the criticisms traditional theater was undergoing in China, Qi was able to see how this particular art form could highlight China’s cultural essence. Upon his return to Beijing, Qi partnered with Mei, who was at the time the most revered and creative of the female impersonators, to bring Mei to major world stages with old and new screenplays. The result of this Qi and Mei collaboration was that China’s theater became a representative of the country’s unique culture in three very different contexts: Japan, the United States, and Russia.

Japan was the first to invite Mei to perform. In 1919, Sino-Japanese relations had been strained for some time, but they were especially strained after the Treaty of Versailles when the Allied Powers at the Paris Peace Conference refused to return German concessions to China and instead granted them to Japan. There was much resentment at this outcome among the Chinese intelligentsia towards Japan. When Mei was invited to Japan’s Imperial Theater on May 1st, the tensions between Japan and China were high—just three days later, students protesting the outcome of the Paris Peace Conference demonstrated before the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Beijing. Nevertheless, Mei’s trip was carried out as planned—in part, perhaps, because the trip had been organized before the Conference. But another reason could be that there was still a great deal of admiration in China towards Japan left over from the Meiji period (1868-1912) when Japan had provided a model of economic, political, and military development and was considered a blueprint for how imperial regimes could move onwards from their imperial past.

Mei Lanfang on stage (Photo by PALM/RSCH /Redferns)

Mei’s 1919 performance in Tokyo was the first time a Chinese actor had been invited to a foreign stage, and the international debut was a tremendous success. Bankers and other wealthy admirers bid large amounts of money for private evening performances, and thousands of people thronged the railway stations to get a glimpse of the actor. When Mei returned in 1924, he again received unsurpassed ovations. It is possible that Mei’s success in Japan was boosted by Japan’s familiarity with male actors in female roles—the onnagata, as it is called in Japan, is part of the Kabuki theater and is especially admired. While Japan’s enthusiasm for Mei’s art may have benefitted from the cultural commonalities between Japanese and Chinese theater, we must not forget that culture and imperialism are inextricably linked in subtle ways and that culture strengthens the imperial processes of colonial powers.

Mei’s next international performance was in the United States in 1930. Qi Rushan and the rest of the company tried to ensure the success of the tour through prior preparation: a newspaper campaign detailing the beauty of Mei’s performances of Peking Opera and the adaptation of topics to be performed for a western audience. Furthermore, they employed a Hollywood producer who made adjustments for the American audiences: highlighting strong and courageous female roles, clear body gestures, and easily understood plotlines. The original ideal of the aesthetically alluring, soft and subtle female beauty that had been so popular in Japan was abandoned for the US performance. These efforts at adaptation paid off. The trip to the US was a commercial success, and Mei became China’s unofficial cultural ambassador. He received honorary degrees from two American universities and in his acceptance speech, he encouraged China and America to collaborate and study each other’s arts and culture. Mei’s tour of the US was an act of cultural diplomacy, where culture in the form of ideas, values, and traditions was presented and exchanged in order to strengthen relations, enhance cultural cooperation and promote national interests. It was mostly devoid of politics. By contrast, the most clearly political of Mei’s tours was the 1933 trip to the Soviet Union.

The Russian tour occurred under very different circumstances. In 1929, Chiang-Kai-shek, the then-president of the Republic of China, severed diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. But two years later, when Japan invaded Manchuria and established the capital of its puppet regime in Shenyang, the Soviet Union, afraid of Japan’s continuous expansion west, suggested they restore diplomatic relations. Chiang did not immediately agree, but eventually sent a Chinese ambassador to Moscow in 1933. The relationship remained lukewarm and the Chinese ambassador was recalled a year later. But Japan’s aggressiveness, however, was a serious cause for the USSR—they needed China’s support, so the Soviet Union tried by different means to bring China’s ambassador back to Moscow. It was at this moment that the Kremlin invited Mei to perform in Moscow, with the hope it would help unite the two countries against their common enemy, the Japanese.

Mei’s performance had an extraordinary impact on Russia’s leading modernist theater artists who had been instructed to reject naturalist theater in favor of Stalin’s social realism, which extolled the virtues and values of communism. The symbolic nature of China’s dan and its abstracted femininity was a sharp break from the sensibility of Russia’s naturalistic theater. Mei’s performances, the music, gestures, clothing, and face paint were all discussed by Russia’s artists at great length and the ‘strangeness’ of the performance—that which had been out of date for Chinese reformers and deemed expendable—became greatly admired by most Russian theater artists (and also by Bertolt Brecht, who was in Moscow at the time).

All of Mei’s trips were originally intended as acts of cultural diplomacy to help disseminate what was unique about Chinese culture. Yet, the organization and reception of each of these tours gave the performances very different meanings. Japan’s enthusiastic reception was due primarily to an innate appreciation of the female role. Because Mei and his troupe fully understood the political tensions between the two countries, they successfully opted to keep their performances on the margins of politics. The performances in the US were also hugely successful and thus accomplished Qi and Mei’s original intention: presenting an art form that was distinctly representative of Chinese culture and elevating the status of Chinese culture to a higher level. On the other hand, Mei’s Soviet tour sprung from the Kremlin’s political maneuver to display political good faith and bring back the Chinese ambassador. This trip was successful diplomatically but also prompted the most interesting discussions on Mei’s performances. Each of Mei’s international tours was a unique and successful example of soft power, and I would argue that we have not seen the likes of them since.

This article benefitted greatly from the works of Min Tian, Janne Risum, Haun Saussy, A. C. Scott and Catherine Yeh.

© IE Insights.