In the mid-18th century, two ancient and now legendary cities buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD were found. The discoveries of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) immediately boosted interest in classical antiquity which was compounded by a subsequent finding in the 1750s. A farmer digging a well not far from where the majestic Herculaneum theatre had been found, came upon something new and rather exciting.

Until this moment, excavation attempts had been primarily focused on nearby Pompeii. But the efforts – led at that time by engineers, antiquarians, and scholars under the direction of wealthy patrons or monarchs – made a quick U-turn; in 1756, Herculaneum and the surrounding area were once again in the spotlight. Thanks to a farmer digging on the outskirts of this ancient port city, a majestic suburban residence, unique in style, was unveiled along the coastline.

Tunneling into the residence immediately revealed surprises: along with marble floors and exquisite frescoes, the largest private collection of sculptures ever found was also discovered: 63 bronze and 24 marble sculptures. The terraced villa is now believed to be the home of Lucius Calpurnius Pisonius Caesoninus (Piso), father-in-law of Julius Caesar – and it has become key to our understanding of Roman interior design. The villa had several levels and stretched over 250 meters along the coastline, with a large peristyle courtyard and a belvedere lookout to the sea.

Ruins of the Villa of the Papyri at the archeological site of Herculaneum

During the excavations, something caught the archaeologists’ particular attention: hundreds of charred papyrus scrolls gathered in some areas of the villa. This was the first excavation during which a library from the ancient world was recovered in such a state of preservation. This library consisted of more than eighteen hundred papyrus scrolls that were charred, then conserved, during the fateful eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Although some papyrus scrolls were written in Latin, most were in Greek and contained, among others, works by Philodemus of Gadara. Philodemus was an Epicurean philosopher and poet, a follower of Zeno, and an innovative thinker in the area of aesthetics. He was known to be a friend of Piso – a likely cause for the collection of works found in his home – and died in Herculaneum around 40-35 BC. In antiquity, Greek works – poetry, tragedy, comedy, and philosophy – were highly appreciated by a large swath of Roman society. In fact, the poet Horace recalled that “captive Greece took captive her savage conqueror and brought the arts to rustic Latium” (Ep. 2.1.156-157).

The Herculaneum papyri were preserved thanks to the high temperatures of the volcanic material that devastated the city. For centuries they remained intact while most of the ancient texts were lost or transmitted through medieval copies and translations. The unknown contents of the charred scrolls soon led to the development of techniques to unroll them so that they could be read. Many scrolls were unfortunately destroyed during these early attempts. For example, Antonio Piaggio, a Piarist monk well known in his time for his innovative techniques to preserve ancient texts, invented a machine that unrolled and flattened delicate papyri. The Piaggio Unroller was key to deciphering the Herculaneum papyri but also caused irreparable damage to them, which in turn meant it took decades to decode the content. The passage of time caused, for example, the disappearance of ink on the scrolls, making it almost impossible to read their contents.

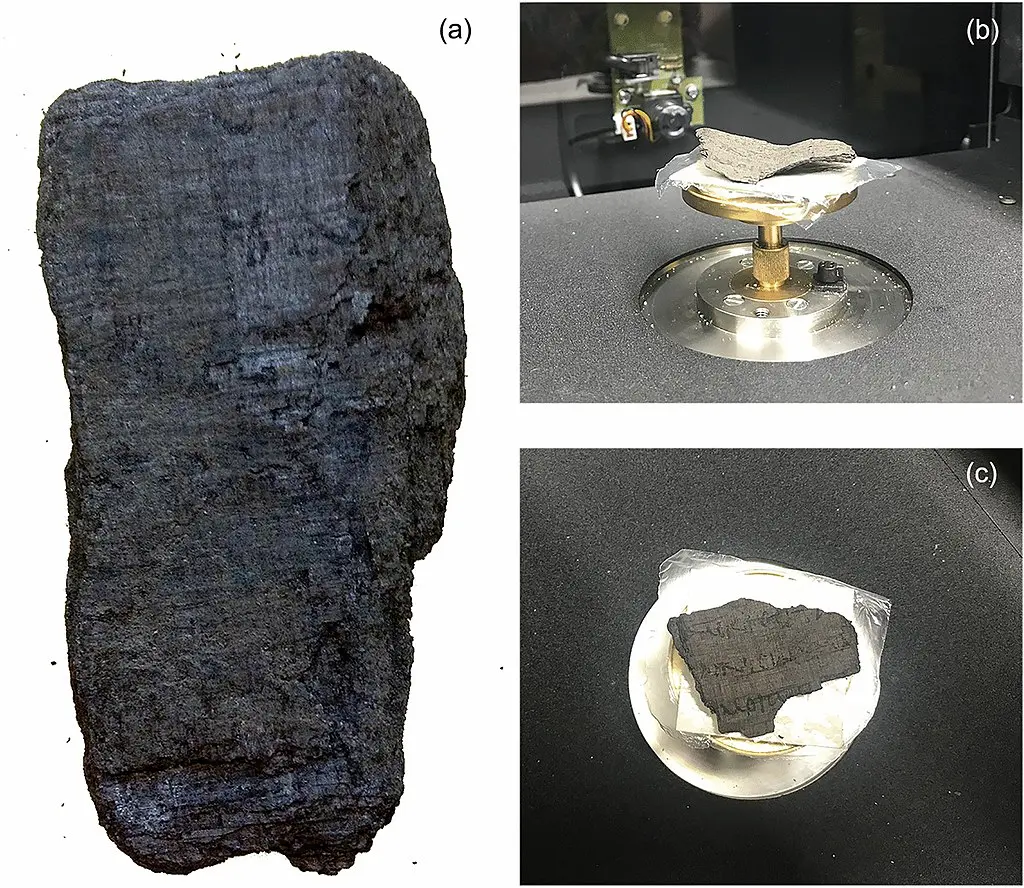

Photos of the papyrus fragments PHerc.1103 (a) and PHerc.110 (b,c)

The turning point came with new digital technologies. Since 2015, experiments in hyperspectral imaging, X-ray tomography, digital microscopy, and computer vision have advanced greatly. And just recently, the papyrologist Graziano Ranocchia of the University of Pisa presented preliminary results of the Greek Schools research project, including the discovery of the exact location where Plato was buried: placed in a private space in the gardens of the Academy of Athens, next to the temple dedicated to the Muses or Museion. How did Ranocchia come across this information? This ground-breaking discovery was made possible thanks to high-tech robotic techniques and a bionic eye that detected more than 1,000 new words in two Herculaneum papyri scrolls that contained the History of the Academy (also known as Index Academicorum) by Philodemus. These two papyri had already been studied in 1991, but now it is possible to read 30% more of the work. Where previously it was impossible to see any trace of language on the scroll, new technologies have helped the identification of the imprint of ink on a charred background.

More than 600 already-discovered papyri from Piso’s villa are still rolled up, waiting to be read for the first time, and many others, written in Greek and Latin, are waiting to be found in yet-to-be-excavated areas of the grounds. The process will now be accelerated thanks to artificial intelligence and impressive progress will be made on the laborious traditional philological translation and interpretation process. Since 2023, the Vesuvius Challenge, an interdisciplinary project launched by the University of Kentucky, has laid the foundations for reading and deciphering the contents of the unpublished scrolls through machine learning and computer vision. Thus, in the last few months, we have seen progress leap forward in spectacular contrast to what had previously been achieved. This has been possible thanks to the application of novel digital techniques.

Being able to approach antiquity through different and new perspectives (made possible with technology and the application of novel techniques) means that our histories will undoubtedly change even beyond these ancient texts. Near Herculaneum and ten years after its discovery, the city of Pompeii was found in 1748. This Roman town, buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius under five meters of ashes, has bequeathed an archaeological heritage of incalculable value. Of the approximately forty-two hectares excavated to date, millions of fragments of paintings, among other types of material culture, remain in the deposits, catalogued, waiting to be studied.

This is where the RePAIR Project (Reconstructing the Past: Artificial Intelligence and Robotics meet Cultural Heritage) comes in. Launched by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in partnership with the Pompeii Archaeological Park and other international institutions, the interdisciplinary project has been applying artificial intelligence and robotics to the reconstruction of two key pieces of Pompeii’s archaeological heritage: 1) the ceiling frescoes of the House of Painters at Work in the Insula of the Chaste Lovers, which were reduced to infinite fragments during the bombings of World War II, and 2) the fresco fragments of the Schola Armaturarum, which suffered from the collapse of the building in 2010. These two case studies are the foundations of a methodology that will work with thousands and thousands of fragments, joining data, and revealing new pictorial scenes that will give us a fuller understanding of Pompeii before the eruption.

Humans have an innate desire to understand ourselves, a pursuit we are born to undertake. A significant part of this journey involves looking and delving into our past to comprehend how we arrived at our present and navigate our current and future challenges. And, because of their good state of preservation, Pompeii and Herculaneum allow us to navigate past narratives, holding so much magic and always captivating us. These ancient cities offer us a glimpse into a society that resembles, in some aspects, our own today – and that view is widening as of late, thanks to the arrival of new technologies, enabling us to gain a deeper understanding not only of ancient life but also of our modern selves, comprehending the mechanisms behind past social constructs and the path(s) traveled until our present.

Humanity will always be engaged in the reinterpretation and re-evaluation of the past, a process that is accelerated and intensified by technological advancements and discoveries that bring new and diverse information to light. The distance between our present and the past is being increasingly shortened thanks to new digital technologies applied to the humanities. Herculaneum and Pompeii are just two examples of a digital revolution that promises unprecedented results, alternative interpretations of our history, and new ways to (re)write our present and future narratives. What’s next?

© IE Insights.