Retirement represents one of life’s most profound transformations – one that can either unlock new opportunities for personal growth or trigger an identity crisis. While traditional retirement once meant a clean break from work life, today’s landscape offers far more nuanced pathways. As noted in The Oxford Handbook of Retirement, “Many countries have started to implement legislation offering incentives to older workers to continue in the workforce once they’ve reached the retirement age… (and) different types of retirement practices, such as flexible retirement, phased or gradual retirement or part-time retirement in addition to the traditional full-time retirement practice.” This evolution reflects a growing recognition that retirement success depends less on the timing of departure from the workforce and more on how individuals navigate their unique transition.

Workers are now taking more control over the timing and manner of exiting their professional roles and, as a result, the act of retirement has transformed from a one-time event into a more flexible process of transition. Of course, even with the variety of retirement options – and even with the global trend of delaying retirement ages – one fact remains unchangeable: retirement is inevitable. Life expectancy will continue to increase, our descendants’ lifespans will grow, and then they too will retire in their later years.

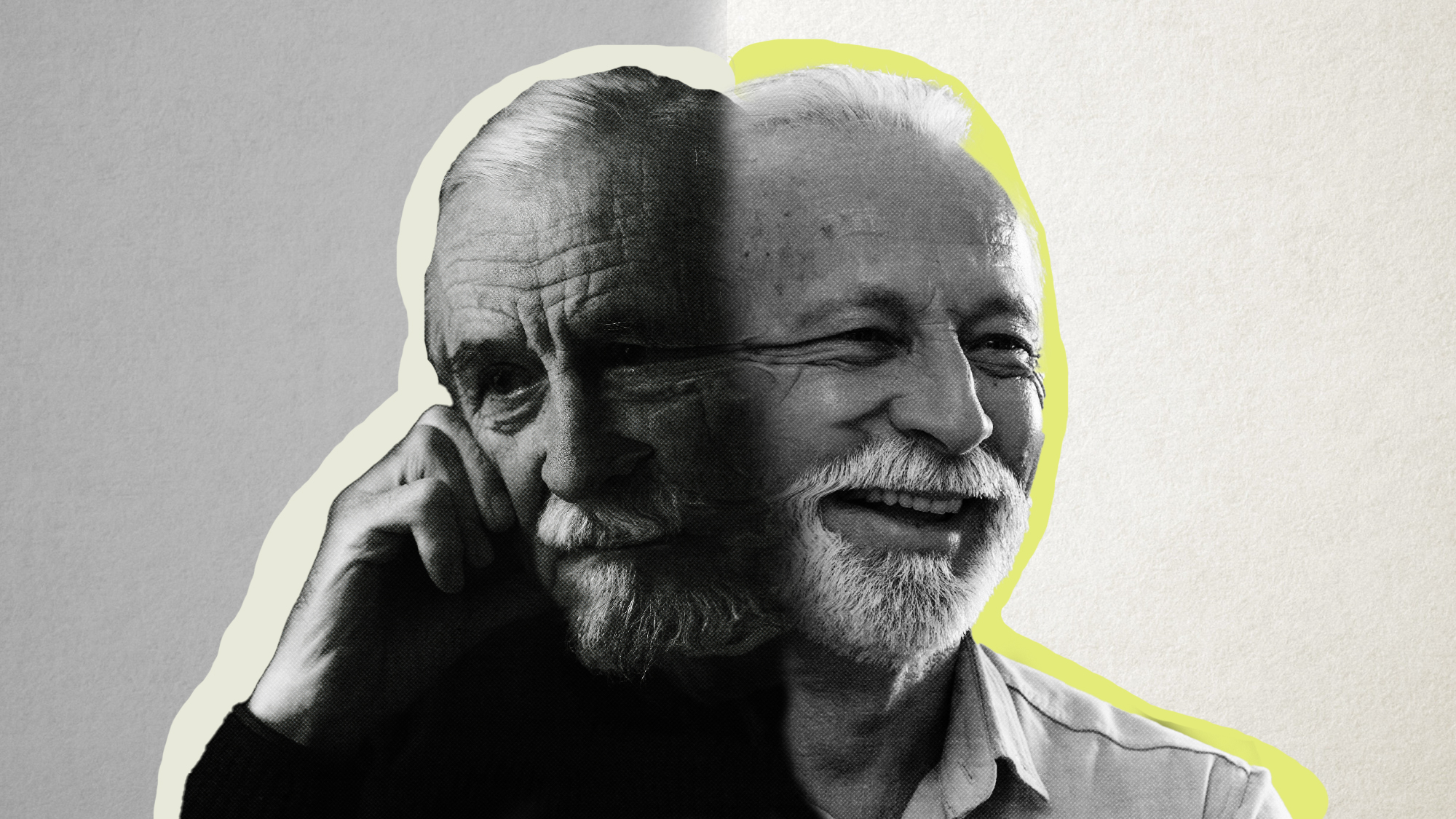

The psychological impact of retirement is a subject of vigorous debate. On one side, concerns focus on concrete losses: the motivation to keep active decreases, and social connections shrink, as does disposable income. Yet others see retirement as an opportunity for greater freedom, a chance to pursue and indulge in personal interests, and an occasion to acquire new experiences or develop long-neglected skills.

Our professional life does more than occupy our time. It stimulates our capabilities, fulfills core needs, and anchors us in society. In a culture that closely links personal value to productivity, retirement represents not just an end to this work, but a fundamental shift in social status and identity. This requires us to readjust psychologically as we move away from a vigorous and structured period of life to a new reality.

The personal meaning we attach to our careers plays a crucial role in this adjustment. Work doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone: for some it represents a true calling, for many it is merely a means of generating income, and for others it is pure drudgery. Those who view their career as the core of their identity often experience retirement as a personal threat, while others may see it as liberation. Most people, however, navigate this rite of passage successfully.

Moreover, in addition to the loss of professional identity and shared purpose, retirees face practical challenges: the end of structured life routines, reduced financial security, and the need to readjust spending patterns. It requires a readjustment of expenses and sometimes giving up small comforts that once brought joy to life. There are frequent concerns about financial changes in anticipation of the rising cost of living and a future need for external care. As author Chip Conley notes, retirement can alter family dynamics, readjusting established understandings and agreements amongst loved ones and raising new expectations (and also concerns.)

The emotional and psychological impact of this transition varies significantly on several key factors: whether retirement was voluntary, how much control individuals have over its timing and process, their age, gender, and whether they have meaningful plans for this next stage. While feelings of emptiness, disorientation, and the fear of irrelevance are common, these reactions – while stressful and even anxiety-inducing – should be viewed as normal responses to a major life change rather than signs of maladjustment. They are not indicative of problems and should not be met with rejection or guilt.

Successful retirement requires personal commitment, self-reflection, and perseverance.

My research, based on interviews with 150 retirees, reveals a correlation between retirement timing and satisfaction. Executives and others who found satisfaction in their careers typically retire at the mandatory age or later, and often seek to extend their careers. In contrast, those who view work as a burden eagerly seize opportunities to retire and leave their job behind.

Gender differences emerged as particularly striking: 66% of women opted for voluntary early retirement compared to 38.7% of men. Women generally experienced smoother transitions, while men more frequently reported struggling with the transition and missing workplace challenges.

Retirement brings a sense of liberation and one’s focus shifts from external demands to internal priorities. This newfound freedom from the workplace schedule has the potential to create space that allows us to become more authentically ourselves. We can rediscover neglected aspects of ourselves that we had put aside and, with determination, set in motion projects that give new meanings to our penultimate life chapter.

This potential for change and growth is enhanced by modern realities: retirement today is a prolonged and reasonably healthy stage in life, offering a unique vantage of seasoned wisdom combined with opportunities for learning and leisure. Moreover, our growing awareness of life’s finite nature makes time especially precious and its use more compelling.

According to my research, men tend to approach retirement with structured precision, maintaining fixed schedules and activities and self-imposed discipline to stay active. Specifically, 37.6% of retired men focus intensely on selected activities. Some continue using their professional expertise in retirement, while others pursue entirely new directions. The most productive among them create structured yet flexible plans that foster new interests, perspectives, and self-discovery. A few develop new careers or businesses, others join associations or develop new skills, and many look for new ways to get closer to their family, perhaps compensating for the distance created during their active career period.

Women, in contrast, typically embrace a more fluid approach to retirement, maintaining stronger family connections while being spontaneous in their daily routines. Nearly half (49.1%) explore various recreational activities, and often look at retirement as compensation for years of balancing career and family responsibilities. Many women describe retirement as a renewal of individual identity, with newly acquired autonomy creating a clear “before and after” in their lives.

These insights have important implications for organizations and executives. Companies can better support retirement transitions by offering flexible pathways that acknowledge our varying attitudes toward work – and phased retirement programs, mentorship opportunities, and retirement coaching could help both those eager to move on and those who wish to remain engaged professionally. Such initiatives not only ease individual transitions but also help organizations retain valuable knowledge while managing smooth succession planning.

For executives approaching retirement, it is important to take careful consideration of one’s unique situation – and to do so beyond financial considerations. Those who derive significant meaning from their leadership roles should consider how to transition their expertise and influence into new opportunities. For example, they could take on board positions, consulting roles, mentoring, or joining non-profit organizations. The key is to start thinking about and planning this transition well before the retirement date. This will help individuals build new networks and identify opportunities that match both their skills and desired level of engagement.

Ultimately, in retirement, there is the possibility for loss as well as gain, but the final outcome will depend on how we navigate the road ahead. Every challenge also brings an opportunity for change and fulfillment. But it must be borne in mind that successful retirement requires personal commitment, self-reflection, and perseverance. Retirees must often push beyond their comfort zones and dare to step off the beaten track. In this new chapter, self-worth becomes increasingly tied to achieving personally meaningful goals rather than external validation. Nancy Schlossberg of the University of Maryland, who studied retirement after experiencing it herself, wisely counsels: “You don’t know how it’s all going to unfold, but I think people need to embrace ambiguity, because there is ambiguity, and there is no quick answer.”

© IE Insights.