What is the European Parliament?

The Parliament is one of three legislative bodies and a key institution of the the European Union (EU), but how does it work? Let’s start with some basic facts:

The Parliament is composed of 705 members (MEPs).

The European Parliament was founded in 1978.

It represents the second-largest democratic electorate in the world (after India), with an electorate of over 400 million eligible voters.

It is based in three cities: Brussels, Strasbourg, and Luxembourg City.

It is the only directly elected EU institution.

The current president of the European Parliament is Roberta Metsola of Malta.

It functions in 24 official languages, and all official documents are translated into each of these languages.

The Parliament’s main roles can be broken into three categories: legislative, supervisory, and budgetary.

Legislative

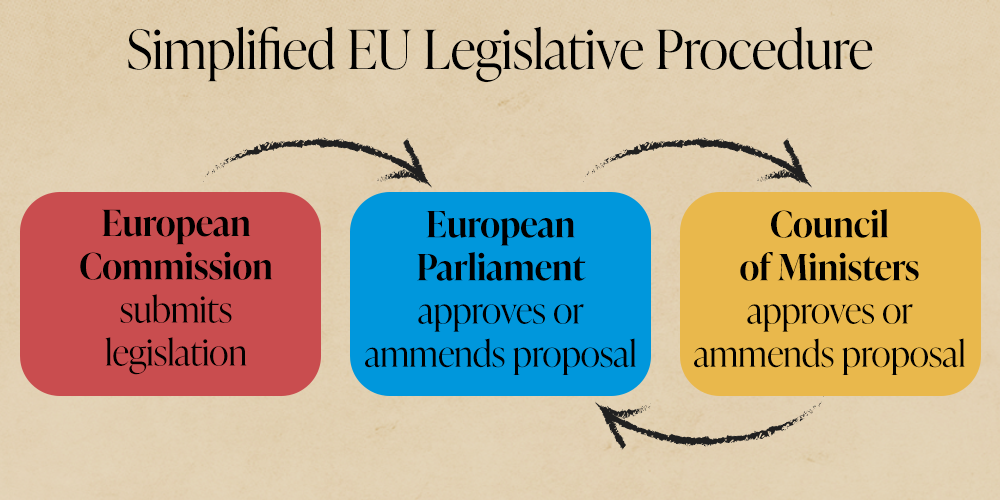

In EU procedure, the European Commission first proposes legislation, and the Parliament then deliberates and suggests amendments through 20 committees. If the legislation is passed or amended, the European Council then finally considers the legislation. This process is known as co-decision.

It’s important to note that EU laws are superior to national laws, meaning member states cannot pass national laws that contradict EU laws. Only the EU can pass laws in certain areas: the customs union, business competition rules, trade agreements, and monetary policy (for countries in the eurozone).

Supervisory

The Parliament oversees the actions and decisions of the European Commission and other EU institutions and agencies. This supervisory role allows it to monitor the use of the EU budget and to ensure that EU law is correctly implemented. It includes the power to hold hearings and demand explanations from commission officials.

Budgetary

The Parliament shares annual budgetary power with the Council of Ministers, and together they decide what the European Union will spend for the year.

How do the elections work?

Seat Allocation

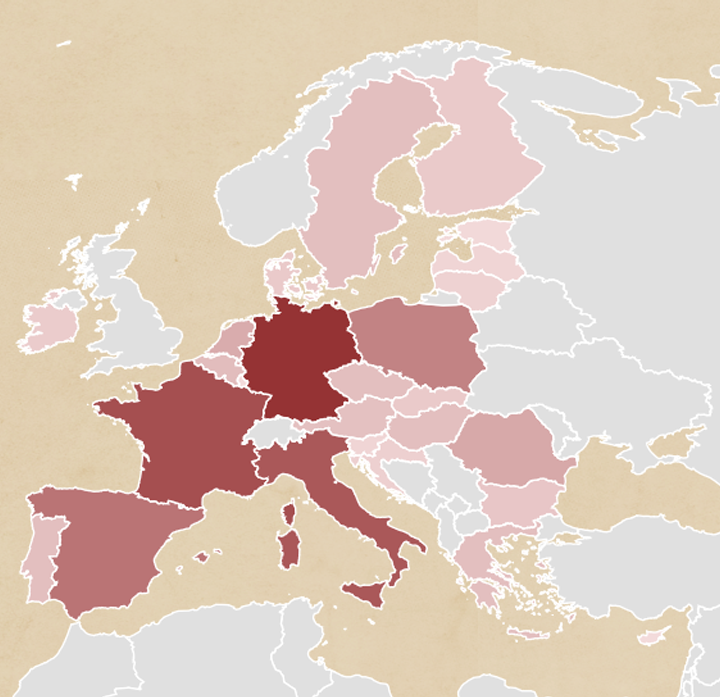

Each state is given an allocation of seats proportional to its population. The largest countries are Germany (96 seats), France (81 seats), and Italy (76 seats), while the smallest are Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Malta (all with 6 seats each). See the full allocation in this map:

Germany

96 seats

Netherlands

31 seats

Belgium

22 seats

France

81 seats

Spain

61 seats

Portugal

21 seats

Italy

76 seats

Austria

20 seats

Slovenia

9 seats

Croatia

12 seats

Hungary

21 seats

Slovakia

15 seats

Poland

53 seats

Lithuania

11 seats

Czechia

21 seats

Latvia

9 seats

Estonia

7 seats

Finland

15 seats

Sweden

21 seats

Ireland

14 seats

Romania

33 seats

Bulgaria

17 seats

Cyprus

6 seats

Greece

21 seats

Luxembourg

6 seats

Denmark

15 seats

Electoral System

Each member state is free to choose its own system for the election of MEPs, but the system must be a form of proportional representation (PR).

Under proportional representation, parties gain seats in proportion to the number of votes cast for them. For example, if a party gained 40% of the total votes, a perfectly proportional system would allow them to gain 40% of the seats.

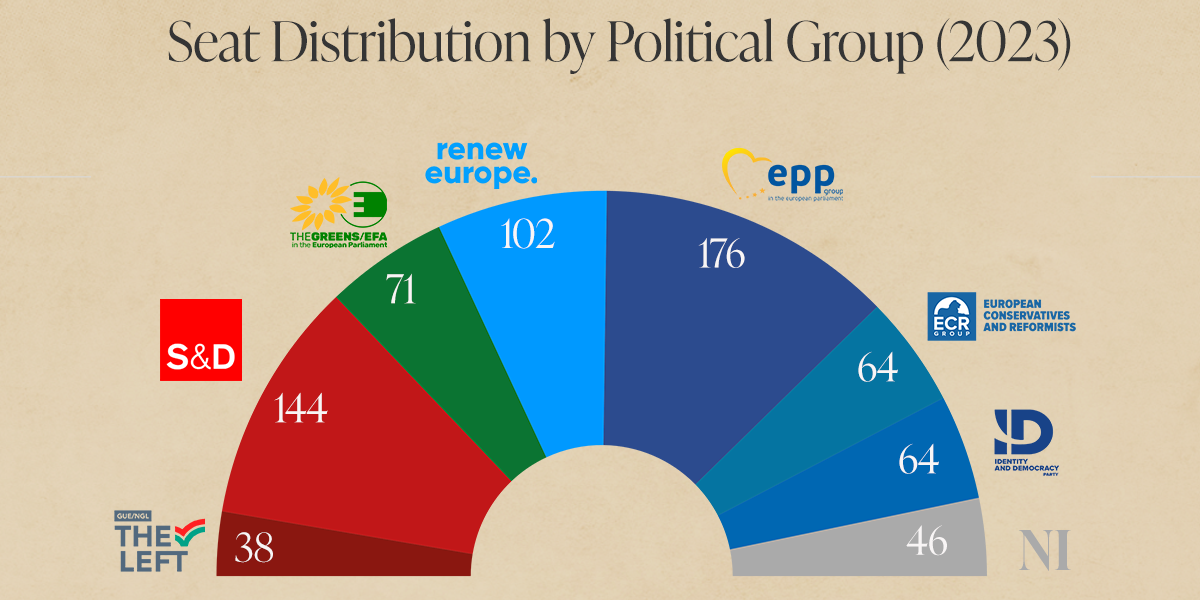

Political Groups

The Members of the European Parliament sit in political groups – they are not organized by nationality, but by political affiliation. There are currently 7 political groups in the European Parliament:

- Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats)

- Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament

- Renew Europe Group

- Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance

- European Conservatives and Reformists Group

- Identity and Democracy Group

- The Left group in the European Parliament – GUE/NGL

Those who do not belong to any political group are known as Non – Inscrits (NI).

This is how the seats are currently distributed between these groups, and where they fall on the political spectrum:

Why does it matter?

The EU elections carry immense global significance, shaping the continent’s direction toward unity or retreat into national borders amid rising Euroskepticism, writes Ángel Alonso Arroba.

The forthcoming EU elections will be critical not only for the Union itself but also for the wider world. We Europeans will choose the EU we want: either a continent that retreats to national borders and is led by parties opposed to further convergence, or one that continues its path toward greater integration and understands that Europe can gain much more from continuing to come closer together.

The overall expectation is that, while traditional parties (people’s, social democrats, liberals, greens) may manage to hold the fort, we may witness a considerable advance by Euroskeptic forces, particularly those from the extreme right. How significant will those gains be? That’s the question on everyone’s mind.

Strictly speaking, on June 6-9 voters will elect the 705 members of the European Parliament. But the results coming from the ballot box will also shape the equilibrium of forces and leadership in other key institutions: the Commission, the presidency of the Council, and several other powerhouses oiling the EU machinery. Ultimately, the elections will determine the orientation of policies emanating from Brussels in the years to come and affecting our daily lives, ranging from fiscal and monetary policy to migration, to social issues, and, critically, the energy and digital transitions.

However, we should look beyond Europe to understand the true dimension of this election. We are living in a volatile moment for global affairs, characterized by growing divides and heightened competition. While over the past decades, the EU has been a model for how countries can overcome their historical grievances and give up sovereignty to offer a better life to their citizens, this has been put into question by the different responses to the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, as well as perceptions of double standards in key areas such as decarbonization and international trade. The result is a deepened sense of retrenchment, selfishness, and lesser commitment to openness and multilateral collaboration. This change in standing may prove very damaging for Europe and send a worrying message to the rest of the world.

Given the times that we live in, Europe should return to being a beacon of hope and forwardness, rather than falling into negativity and backwardness. Much is at stake as Europe casts its votes, both for the continent and beyond.

© IE Insights.