It is difficult to overestimate the importance of this year’s US election for the world order and the global economy, or more specifically, for human security and prosperity worldwide. This applies especially to Europe, a region dependent on the transatlantic link for trade and security.

Under President Donald Trump, the US not only showed a lack of interest in the world order, but also eroded the institutions upon which it rests. This includes withdrawing financial support for the UN, blocking the WTO’s dispute resolution, and questioning and undermining NATO. Revisionist powers have increased deliberate provocations, subversive campaigns, and the systematic erosion of our competitiveness with industrial espionage and acquisitions.

Things were already going in the wrong direction, but with COVID-19, the true misery began. The Chinese Communist Party has advanced its positions militarily and with the introduction of new security laws in Hong Kong. European Commission President von der Leyen surprised many when she identified China as being responsible for cyber attacks on hospitals and research centers in Europe. Similarly, the Kremlin has been making advances during the crisis in Belarus, with its influential operations towards the US election and the alleged poisoning of Alexei Navalny.

Conflict today is largely digital. The big tech companies now constitute the actual infrastructure through which we access the internet. They are, in essence, information flows whose business model is to manipulate these to make money from advertising. Profit is made by collecting and analyzing as much data as possible and by maximizing content most likely to get users hooked. This is good for finding funny cat videos, but not so much for the cornerstone of our democratic debates.

This system is particularly vulnerable to both domestic actors, such as Cambridge Analytica, and to external players, such as the Russian and Chinese intelligence services, who are competing for support of their narratives. Nonetheless, foreign attempts pale in comparison to Trump’s own misinformation and statements that the elections was fraudulent. In order to fix the information arena, it needs to be a public good with the necessary supporting legislation, but malign influence from foreign actors also needs to be deterred.

The pandemic emphasized and increased the importance of the digital arena for power today. One of the most interesting yet least noticed events during the pandemic was how two private companies determined how 3.2 billion smart phones worldwide could be used for contact tracing. Not even Europe’s most powerful states – Germany and the UK – were able to implement their own solutions, but had to comply with the decentralized protocols of Apple and Google.

In January, Apple’s market value surpassed that of the entire DAX30 – Germany’s 30 largest companies. The German economy is the world’s fourth largest, and Europe’s biggest. Apple surpassing DAX30 underlines how Europe is lagging behind and why the EU strives for “technological sovereignty” and to become a “global digital player”. This is correct, but so far progress is nowhere to be seen. European companies received only 11% of global venture capital in 2016, and in 2018 Europe could claim only four of the 100 leading AI startups.

The technological arms race is shifting geopolitical conflict from the public to the private. The Trump administration took a noticeably tougher stance to China in particular to Huawei and ZTE. During these last years, the US has taken a number of actions with the aim of decreasing dependence on China and, in effect, China’s global influence. For instance, in 2019 the US Department of Commerce placed Huawei on the license requirement register, the Entity List, which requires permission for US producers to supply parts to Huawei. This is in particular substantial as US companies are critical for the supply of semiconductors, and the move is likely to significantly impair Huawei’s ability to build smart phones and mobile networking equipment in the short term.

In the medium term, the Made in China strategy is a long-term and purposeful effort from China to achieve technological sovereignty and the ability to pioneer technological change. Already today, the Chinese Communist Party has a formidable combination of pioneering tech giants which generates and controls large amount of data. This data is available for the state to both utilize as tools of social control, but also to train machine learning systems and get further ahead in the field of AI. This is a reason why China is at the forefront today, if not edging ahead already.

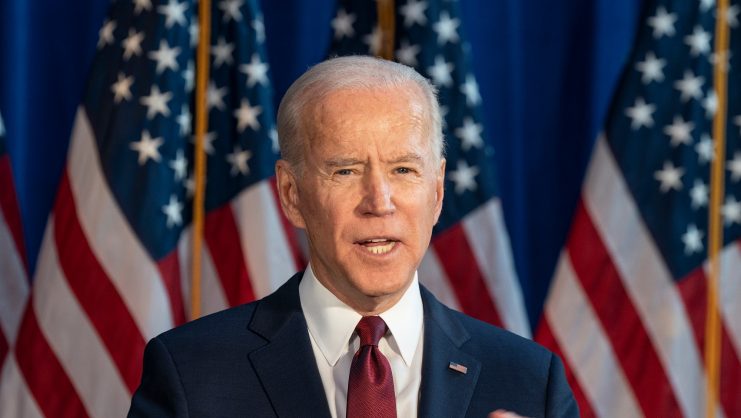

The technological arms race and the global conflict are breaking up complex supply chains across the world. This is not solely an unintended consequence but, from both parts, a purposeful effort to decrease one’s vulnerabilities for influence. Even with Joe Biden winning the election, the technological decoupling will continue. There is widespread political support for a tougher stance on China, and popular backing for trade barriers and tariffs. Additionally, securitization of supply chains, components and raw materials will redraw trade and production flows for a long time.

On the outer edge of all this, the EU is struggling to find its strategic agency and digital sovereignty. The European Commission’s stated objective is to: freely set goals and act in cyberspace, independently control digital tools, and maintain traditional state sovereignty in handling digitalization. Needless to say, this vision is far off and there are few quick fixes. The cell phones, operating systems and app stores which are the most powerful today are rarely or never European.

Reviving European agency in the digital domain requires vision and leadership more than anything else. The US decision to be first on the moon is perhaps a worn-out example, but it underlines the strength of determination. And Europe is not starting from scratch – it is full of talent and technology. Indeed, in the not too distant past, Europe was a leader in digital competencies.

A key part in making European companies able to grow as much as American and Chinese companies is access to a larger market. This naturally entails enacting the European digital single market. The development of European technological leadership requires building a stronger financial ecosystem so that promising companies are not all bought by foreigners. A good example is Spotify’s CEO Daniel Ek’s pledge to invest $1.2bn in European moonshots (early-stage startups). The opportunities to attract leading talent is also vast with current infractions on the H1B visas in the US. We need to support the leading European universities so they can attract leading international talent and increase their capability for the third role, knowledge-transfer, in which the leading US universities are doing better.

Europe’s long-term security and wealth are increasingly threatened by its lack of technological leadership. Otherwise, some of the most impactful decisions affecting the EU will continue to be taken by foreign technology companies without much regulation. It is up to Europeans to rectify this lack of leadership in order to take back control of their own technological domain.

This is an expanded version of an article originally published by the Swedish daily Dagens Industri.

© IE Insights.