A group of senior managers in a Fortune 500 medical supply company in Chicago decided that their company – facing sluggish performance and increasing competition – needed a more entrepreneurial culture. So they created a “Giraffe Award” to recognize managers who stuck their neck out the most to innovate. Although everyone left the meeting pumped, no one received a “Giraffe” …ever!

We’ve seen this type of entrepreneurial whiplash before. First, managers become intrigued with the possibilities of bringing the entrepreneurial spirit inside their organization. Next, they seize up at the thought of doing something new that may turn out “wrong,” hesitating to bet company assets (and their own reputation) on an ambiguous possibility. Finally, freezing up in the face of the new, they let the comforts of the status quo lull them into complacency.

“I want to be more entrepreneurial. I really do,” corporate managers from every continent have told us. Underneath, we sense that most of them are gripped by fear of venturing off the well-trod path of past success. Two fears keep them up at night: not knowing enough or being judged “wrong” in their new ways.

Hampered by Legacy

Every corporate culture rests upon a view of the world. All too often driven by a control-and-improve paradigm, its systems naturally evolve to spotting, eliminating, and correcting mistakes. What is acceptable is framed only by what’s already been validated. The trouble is, it’s rather tricky to drive forward by only looking in the rear-view mirror, especially when the terrain keeps changing.

Ever wondered why horse-drawn carriage companies did not evolve into automobile companies? When the managerial worldview is mistaken for the world outside, it spins its own legacy cocoon that suppresses entrepreneurial thinking. Framing any action that does not match the past as (gulp!) a mistake implies that the status quo seldom is questioned.

Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon.com, in his annual letter to shareholders, emphasizes the importance of having the flexibility of “Day 1,” when there was no legacy to subdue anyone’s entrepreneurial spirit. The thing to fear, he said, is a “Day 2” point of view:

“Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.” We believe an entrepreneurial company begins with entrepreneurial managers. The challenge is to help managers overcome their fears of “not knowing enough” or “being wrong.” Here are three ways to do just that.

Forget Right and Wrong

Entrepreneurial thinking starts with recognizing that most companies treasure their legacies to the point of obscuring future possibilities.

Right-Wrong categories apply only to the past. They need facts. Yet there are no facts in the future. Tomorrow brims with possibilities — seldom a replay of yesterday.

“Focus on the future” is an unassuming prescription for revealing the limitations of legacy thinking. By simply looking ahead to a world not nailed down by facts, the right-wrong label is always behind you — and it can never catch up with you.

Although both Fujifilm and Kodak had successful pasts built on photographic film, Fuji was focused more on the future. The business divided its efforts between getting the best profits it could from the outgoing film market, while gearing up its other operations and branching out into areas like skincare, graphical art supplies and equipment servicing. The past also looms large as “kick in the teeth”, as in the 1,000+ rejections of Colonel Sanders and his Kentucky Fried Chicken recipe, the 51 failed games by Rovio before the success of Angry Birds, or Walt Disney’s being fired from a newspaper for not being “creative enough,” and going bankrupt with his concept of Laugh-O-Gram. To call these experiences “failures” is to remain locked in the past.

Wear a Visibility Coat

In Harry Potter’s world, an invisibility cloak helps you go around unseen by anyone else. Entrepreneurial managers must do the opposite; i.e. put on a visibility cloak, to reveal things not apparent to other people. They need to look for what’s not there, products or services that will be needed once the marketplace awakes to its presence.

Brian Chesky saw an Airbnb concept in a world of ample hotels and motels, while James Dyson had a vision of a bagless vacuum in a world of bags. The former met frosty reception by seven prominent Silicon Valley investors. The latter could not stir established companies like Conair and Black & Decker and venture capitalists and banks refused to back it. [Dyson’s vision persisted after 5,126 prototypes.] Both successes show that people would like what is not there — if someone could only see to do it.

Entrepreneurial thinking relies on what is possible in the marketplace and prompts us to “imaginate” (an old Scottish word) beyond what there is. One has to look for what’s not there, and simply ask “Why not?”

Don’t Overthink

In 2019, IBM launched a new event called “Think” so attendees could learn about all the cutting-edge technology and applications shaping the world.

The problem is that “thinking” has been misconceived by too many managers. “Paralysis by analysis” arises from a penchant for reducing priority decisions to analysis and debate, looking for clear answers to neutralize fears.

Jeff Bezos is savvy to the dangers of overthinking. His idea of “high-velocity decision making” recognizes that waiting for all information is detrimental. “Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. Plus, either way, you need to be good at quickly recognizing and correcting bad decisions.”

Being entrepreneurial values doing for the sake of doing. Only action can provoke the world to respond. Go. Do. Act. Invite serendipity by keeping things in motion; remember: the future is shaped not by past facts but by unrealized possibilities.

You can avoid mistakes by never doing anything new. Or, just like a giraffe, you can stretch your neck into the future.

And Retain Humility and Reflection

There is no recipe for success. The real trouble is believing there is one.

The simple heuristics we advocate are there to help you climb out of the self-imposed box of looking for the “right” answer.

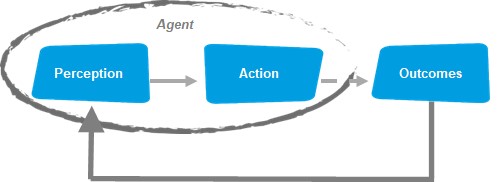

Taken together, they can help you develop as a kinetic thinker. Our Kinetic Thinking framework recognizes the recursive nature of our entrepreneurial life journey: what we do affects what we know and want, which in turn affects what we do… and so on in an ever-expanding spiral.

This spiral turns into a closed loop when we succumb to our habits and ignore the need to constantly reshape perceptions. To be reflective is to become aware of the beaten path and to be humble is to recognize there is a vast, unknown space to be explored.

Recursive Model of Entrepreneurship: Kinetic Thinking 2020©

Becoming a kinetic thinker is about taking control of the levers of thinking at our disposal: what we see (perceptions) and what we do (actions). Where we normally focus on what already exists, we can simply open up our imagination and look for what’s not there. And where we normally seek justification for doing something, we can simply adopt the playful stance of ‘why not’, of inviting surprise.

To help you understand how you think when facing new situations, and how you can develop your own thinking, we have created a simple “mirror-map” toolkit: a 5-minute assessment that comes with a personal thinking style profile, a map of thinking styles, and possible developmental moves.

To take the free assessment follow this link: https://www.kineticthinking.com/ep-style/

© IE Insights.