These days, it’s impossible to be unaware of the abuse that many women receive on social media, from rape threats to death threats to threats of all kinds. Anonymity, or the feeling of it, tends to lead to cowardly behavior. But before you imagine the threats coming from some angry guy sitting alone at his computer, consider the possibility that these now commonplace attacks on women may be about more than just a few sexist men saying nasty things on Twitter.

Organized and deliberate gendered disinformation campaigns are potent tools that authoritarian leaders and their allies use to tighten their hold on power and silence critics. They target women with the aim of delegitimizing their participation in political life, deeming them, according to a report for the Brookings Institution, “inherently untrustworthy, unintelligent, or too emotional or libidinous to hold office or participate in democratic politics.”

Women activists, journalists, and politicians aren’t the only targets of online disinformation campaigns. Plenty of men have fallen prey as well. But because women have a historical deficit of participation in politics, and because women have long been silenced and shut out, continued attempts to keep them on the sidelines pose a special threat to democracy and its capacity to become more inclusive. However, this is about more than just fairness, as these disinformation campaigns promote democratic backsliding around the world. Fighting them should be a foreign policy and national security priority.

Disinformation campaigns fall into two camps, the first being state-aligned attempts to silence internal critics or opponents. This is a trend we see particularly from regimes run by strongmen such as Vladimir Putin in Russia, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey. These leaders have all used gendered disinformation not only to attack female critics but to attack feminism itself.

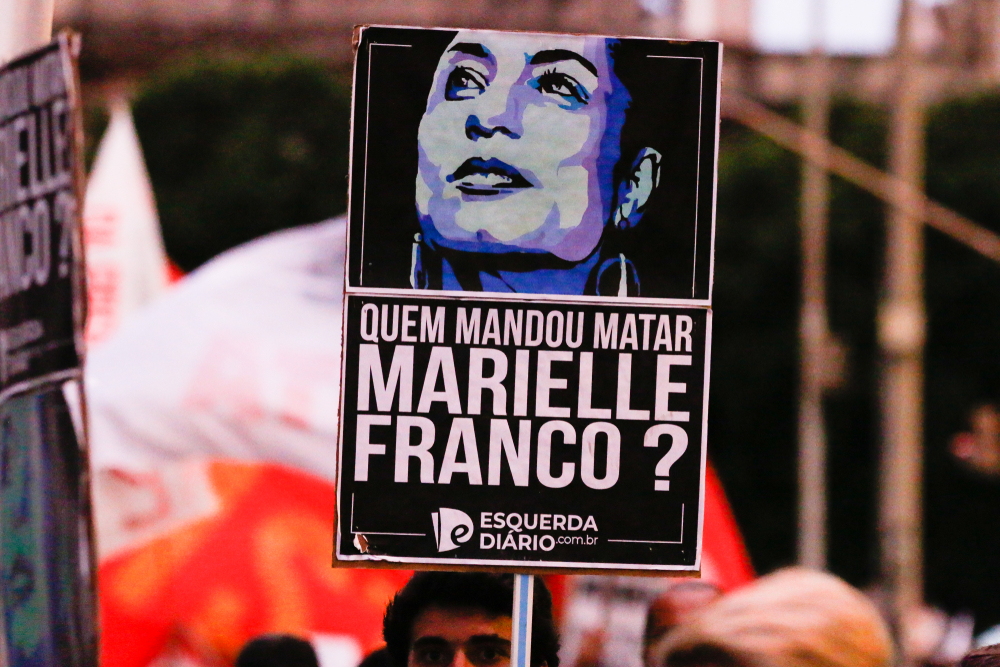

Marielle Franco, a human rights activist, paid the ultimate price for speaking out on behalf of the poor and the marginalized in Brazil. Like many authoritarian leaders, Jair Bolsonaro doesn’t like criticism, but he especially doesn’t like it from women who are Black and bisexual like Franco. She and her driver were assassinated on March 14, 2018. This triggered mass protests, which kicked the so-called “Office of Hate” into action.

“Office of Hate” is a group of bloggers, prominent businessmen, aids, and lawmakers who are close to Bolsonaro, and even includes his son Eduardo. This network has a history of spreading lies about Brazil’s democratic institutions and the people with whom they disagree. Hence, they let loose an onslaught of fake news connecting Franco to drug dealers and painted her as someone who led an “immoral life.” It doesn’t stop there. Journalist Bianca Santana, another Black, Brazilian woman wrote an op-ed in the Guardian in July of 2020 about how Bolsonaro targeted her in a speech two days after she had published an article in the Portuguese language website UOL reviewing the evidence via a flowchart of Bolsonaro’s links to Franco’s assassination.

The group has been under investigation and, in an op-ed in the New York Times, another Brazilian female journalist, Patrícia Campos Mello described how the hate fueled by Bolsonaro’s supporters online had spilled into the streets. Her reporting on fake news has also turned personal for her: after publishing an exposé in the newspaper Folha de São Paulo about the business leaders involved in the “Office of Hate,” she became a target herself. Photos of her face were pasted onto pornographic images that claim she is a prostitute, with messages telling her that she should be raped. In describing how she and so many other female journalists have been subjected to this kind of treatment, Campos Mello warns, “I’m not sure for how much longer we will be able to resist Mr. Bolsonaro and his followers.”

Placard reading “Who ordered the killing of Marielle Franco?” held at a protest in Rio de Janeiro, 2019.

The second type of gendered disinformation is transnational, aimed at discrediting critics and opposition in other countries. Often, this is akin to state-aligned attempts to silence critics but it also serves to undermine the internal workings of democracy in the target country, which in turn undermines democracy in the world by showcasing democracy as chaotic, unstable, and even untenable.

Ukrainian MP Svitlana Zalishchuk gained notoriety in 2017 when she spoke at the UN about her country’s war with Russia and its impact on women. The 32-year old Zalishchuk told world leaders that Ukrainian women have had to shift their focus “from equality to survival.” This turned her into a target and soon afterwards, a fake tweet circulated that claimed she had promised to run naked through the streets of Kiev if the Ukrainian army lost an important battle to the Russia-backed separatists. The campaign was accompanied by fake images of her naked. “It was all intended to discredit me as a personality, to devalue me and what I’m saying,” says Zalishchuk.

This sexualization of women is a common and easy way to attack them and, as Zalishchuk astutely pointed out, the intention is to discredit and devalue their voices. While “using “fake news” to label any information one doesn’t like has replaced “propaganda,” it has proven even more effective for governments and powerful organizations to simply attack the credibility of the source outright. In this sense, women in politics are especially vulnerable since they must fight deeply ingrained stereotypes in order to establish their credibility.

Svitlana Zalishchuk speaking at an anti-corruption forum in Kiev, 2015.

Russia is rightfully famous for its disinformation prowess, perhaps most notably in the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential election campaigns. The data analytics firm, Marvelous AI, used artificial intelligence to track gender bias in the 2020 Democratic primaries in the United States. They found that the female candidates faced attacks at higher rates from the men from “low credibility accounts” including bots and trolls. Furthermore, these attacks centered around the candidates’ character rather than their policies. A most persistent narrative that dogged Kamala Harris, for example, is that she made her way to the top of American politics via favors from powerful men. This is perhaps the most stereotypical allegation thrown at successful women.

In Europe, the EU Disinfo Lab released a report regarding gendered disinformation tactics during the Covid-19 pandemic, which found that “Misogynistic narratives tend to produce either a negative representation of women as enemies and opponents in public debate or a pitiful depiction of women as victims, often in order to push a social or political agenda.” The report notes that the 8M demonstration in Madrid was framed as responsible for the acceleration of the pandemic and that this was “by far the largest campaign of gendered disinformation encountered in a single country during the period considered.” Furthermore, the campaign targeted female politicians in particular and, on top of it all, studies of other campaigns during the pandemic showed that women were framed as helpless victims.

Why should any of this matter to you if you’re not a woman, or you’re not a woman running for office? Because gendered and sexualized disinformation undermines democracy by suppressing the voices of half of the people on earth. Universal suffrage has become the norm in most democratic states, but representation remains woefully far from equal. According to UN Women, only 22 of the world’s countries are led by a woman head of state or government and just 25% percent of the world’s national parliaments are made up of women. Democracy is meaningless if it excludes a big swath of society, let alone one half of it.

At least in Western societies, girls receive as much education and often even excel more than their male counterparts. In fact, boys falling behind has rightfully become the subject of much consternation. However, when I bring up the issue of women’s participation in politics or at the top level of business, the men in my classroom or in social settings often sing the same sad refrain, “well, as long as she is qualified.” As if there were a shortage of qualified women coupled with an abundance of overqualified men who are being passed over for jobs.

The fight for women’s equality is plagued by the fact that we are a gender – and this cuts across all ages, colors, races, nationalities, economic and education levels, political ideologies, and religious beliefs, let alone sexual orientation and gender identification. This brings a cultural richness to feminism, on the global scale, but also the seemingly impossible task of demanding equal rights for so many women, when we can’t even quite agree on how to define that equality.

Women’s rights are the litmus test for human rights and democracy, and wherever they are under attack, we know that democracy is really at risk.

If the participation of all is critical to democracy yet women’s participation continues to be a challenge, then any attempt to subvert this participation is especially threatening not just to democracy but to human rights and liberal values. According to #ShePersisted Global, a cross-national initiative to tackle gendered disinformation, “Women’s rights are the litmus test for human rights and democracy, and wherever they are under attack, we know that democracy is really at risk.”

It’s easy enough to identify these campaigns and be outraged by them. It’s more difficult to actually do something about it. The approach we most commonly turn to is three-pronged, starting with education focusing on media literacy and critical thinking skills. Yet recent research indicates just how uphill this battle is since a feeling of belonging with one’s social identity (such as political parties, ideology, or religion) is stronger than getting the facts right. Next is self-regulation of the traditional and social media, such as stronger fact checking (a fairly toothless solution given the research above) and initiatives such as Facebook’s “Supreme Court” that make decisions on what content stays and what goes. Finally, we approach any government regulation with a cautious eye on free speech.

The authors of the Brookings report, Lucina Di Meco and Kristina Wilfore, insist that gendered disinformation is a national security problem. They believe that, while the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol remains fresh in people’s minds, there is a window of opportunity for a more meaningful debate about the role online platforms play in incubating real-life violence and about how to hold them accountable for the damage they cause to women in politics. Di Meco and Wilfore are calling on the Biden-Harris administration to convene a National Task Force on Online Harassment and Abuse and mention tech regulation that is currently being discussed in the UK and the EU. Such regulation would require these platforms to prove that they are adhering to a “duty of care to their users” in the form of transparency and ensure that algorithms don’t amplify extreme messages just to promote engagement. As one leader, who has herself been the target of many a disinformation campaign, once said before the UN World Conference on Women, women’s rights are human rights.

A version of this article was published in Spanish with esglobal.

© IE Insights.