The International Migrant Stock 2019, a dataset released by the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, estimated that the number of international migrants globally reached 272 million, increasing from 51 million since 2010. Of these 272 million, an estimated 14% or 38 million were below the age of 20.

The term international migrant has many connotations attached to it, but at its core it refers to a person living in a country that does not match their nationality. The reasons that people move from their home country vary, for economic or educational opportunities, a better quality of life, for family, or because of political or environmental factors. Regardless of the reasoning, these individuals are statistically classified in the same category: international migrants.

As someone who grew up as part of this statistic, being a child of international migrants, the increase in this moving population over the past decade does not come as a surprise, it does, however, require us to carry more than just our suitcase.

Children of international migrants are often referred to as third culture kids (TCK), meaning that they are individuals who were raised in a different culture to that of their parents’ or their country of origin. With International migration and TCKs being considered a product of globalization, many of the same concerns regarding the effects of globalization apply to this ever-growing group of individuals. Therefore, understanding the effects of a globalized lifestyle on the leaders of tomorrow is of great interest to psychologists and educators alike.

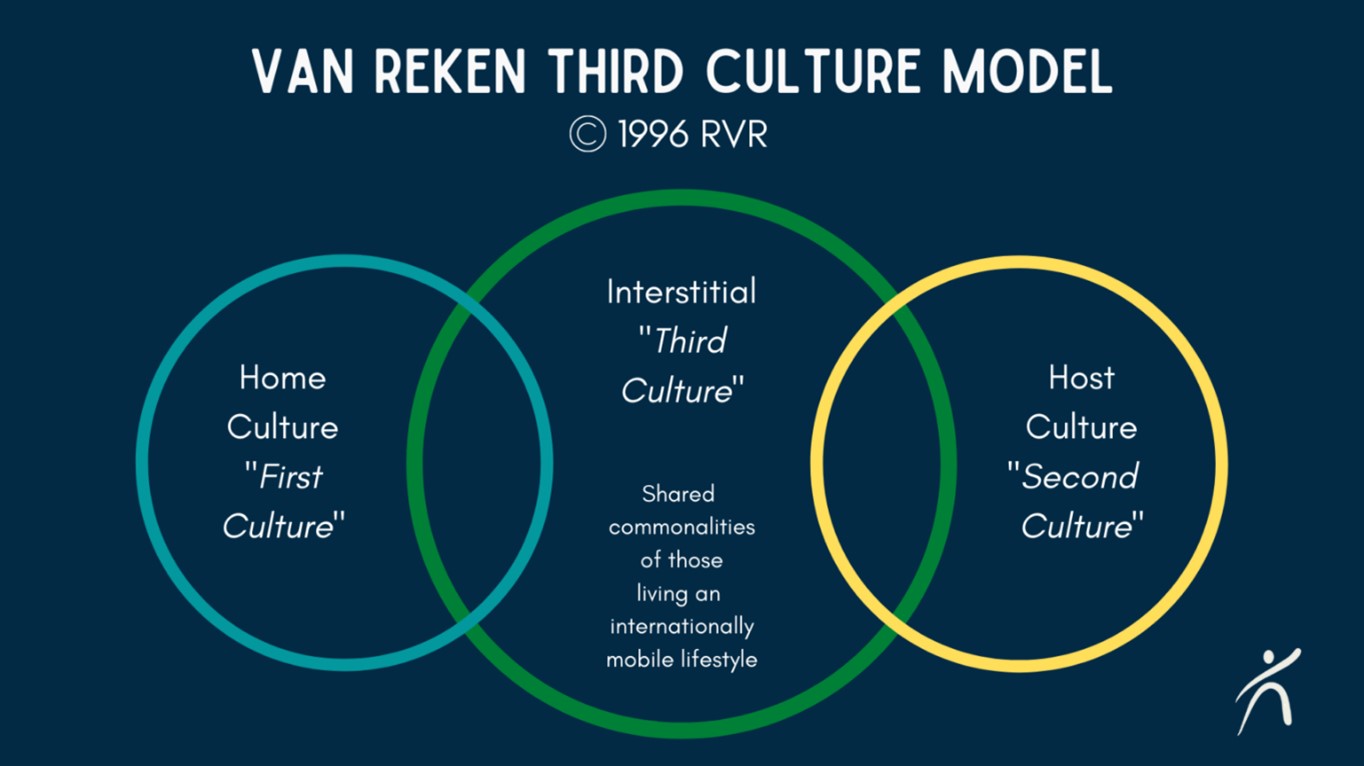

Although the term TCK was first coined by Ruth Useem in 1950, the TCK profile as we know it today was developed by David C. Pollock and Ruth Van Reken.

Through this model, it was understood that TCKs developed a culture between cultures, as they captured pieces of their home and host culture to integrate into their own creation. The creation of this third culture was detailed by Pollock and Van Reken in their book Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds as well as the physiological effects this feat has on children.

Their work found that these children of expatriates, missionaries, military personnel, and others who live and work abroad do not immediately possess a cultural identity of their own in the way that occurs for children whose home and host cultures match. TCKs therefore become ‘cultural chameleons,’ blending in with whichever culture they find themselves in until they are able to develop this third culture for themselves. The lack of a sense of identity can result in confusion regarding an individual’s role in society, leading many researchers to believe that TCKs suffer from delayed development of identity.

This lack of cultural identity can create a sense of rootlessness or restlessness, as, according to Van Reken, “home is everywhere and nowhere.” The resulting loneliness and isolation is a common finding in TCK research, with some experts going as far as to say that “unsettled [international migrant] families may be at risk for psychosocial problems and may be a burden for other members of the community.”

As a TCK myself, who is the product of a family who migrated for work and personal opportunity, going through these studies is incredibly disheartening. The studies that choose to label us only as individuals who lack a sense of identity and belonging fail to recognize the beauty and benefit of our upbringings. While, yes, there is truth in the physiological analysis of TCKs, very few detail how these results are compared to a non-TCK population. Could TCKs simply be better at expressing their emotions of loneliness and confusion? Are these studies simply aiming to show the supposed physiological effects of globalization? And what is so wrong about not knowing where you belong at age 13?

Many of these studies tend to focus on the question “What is Home?”, which is arguably a confusing concept for any individual, as many have formulated a definition that does not match the one found in the pages of an Oxford dictionary.

Our refusal to conform to the traditional definition of home has led us TCKs to be labeled as “culturally homeless” by some who do not consider the term home to be multifaceted. Instead of home being a physical place, we take pieces of our various cultures and use them to build a home within ourselves, therefore building it metaphysically. Furthermore, home is not something that is bound by time, it does not need to be permanent to be a home, as sometimes the places that we lived for the shortest period of time, were still able to be called home.

The biggest shortcoming of the traditional definition and understanding of home is that many do not acknowledge “home” as a feeling. The Afrikaans word “tuis” may be one of the best descriptors of this sentiment as it encompasses the feeling of safety, security. And, most importantly, love. I hope that TCKs will therefore be forgiven if we stutter or stumble when someone asks us the question “Where is home?” Because how is someone supposed to encompass all that into a single set of coordinates? No wonder TCKs are supposedly so confused.

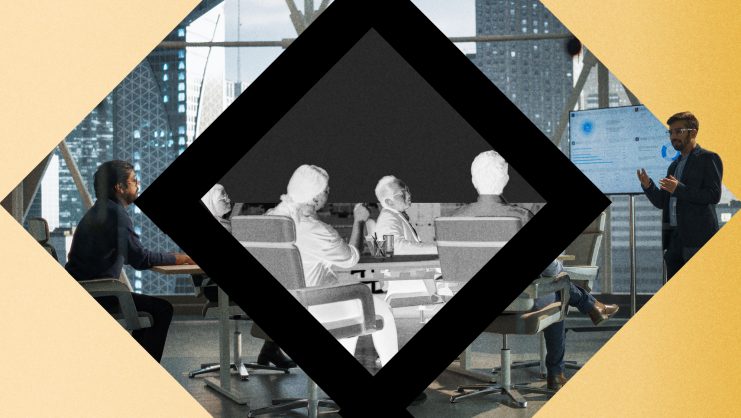

But let’s go past the studies that simply pick at our sense of belonging. TCKs offer a high level of autonomy, problem-solving skills, and willingness to help others in today’s increasingly globalized world. The vast majority of TCKs are multilingual and open to diversity in all senses of the word. Additionally, TCKs are four times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree, further increasing our pull in today’s market. This background not only makes for a competitive candidate in today’s business environment, but a company made up of employees with this profile will be able to compete in the increasingly diverse and global environment. Our preparedness for the constantly changing cultural and social spheres gives us a unique positioning in the workforce, where we often excel as leaders – just look at former US President Barack Obama who lived much of his childhood between the United States and Indonesia.

How can the research on TCKs paint such vastly different images of what these cosmopolitan children offer the world? The truth of the matter is that TCKs are still an “unknown variable” to many. Although it is thought that TCKs have existed since the beginning of civilization as humans explored, or conquered, the globe, TCKs are not the norm in society and can represent, to some, the unfortunate product of globalization, since these so-called troubled individuals are stuck in a limbo without an address. To others, however, this group offers a unique glimpse into a borderless future where the exchange of culture and ideals fosters the creation of mixed identities.

With researchers divided, and even the founding academic Ruth Van Reken criticized for her possible personal bias (being a TCK herself), it becomes clear that there is not a complete understanding what a TCK is yet. Are they – are we – the unfortunate product of globalization or representative of the leaders of the future? This answer will have much to do with what shape we want our world to take in the future. What is clear, regardless, is the world’s ever-growing international migrant and therefore TCK population.

© IE Insights.