The fight against inflation has been a priority for generations, but today we find ourselves in an atypical situation, with very low or even negative inflation in many countries. The consequences of this are not uniform, but rather depend on the circumstances and role of each economic agent. Accordingly, some experts believe that the eurozone, like Japan in the 1990s, is at risk of deflation and years of sluggish growth. The two contexts share clear similarities. The main difference lies in monetary policy: although Japan has lowered interest rates and adopted expansive monetary policies, the European Central Bank (ECB) is generally considered more dynamic.

Despite the financial markets’ concerns regarding the “Japanization” of the eurozone, they generally take the view that the ECB will avert a situation of zero growth and inflation. This is clear in the appreciation (of both fixed-income and equity securities) that occurs whenever the ECB announces possible measures, such as the purchase of sovereign bonds. Logically, in some countries the ECB’s actions should be accompanied by structural reforms. However, these changes tend to be implemented only by stable governments with the necessary political support, a situation that is not always the case in those eurozone countries most in need of such deep reforms.

Consequences

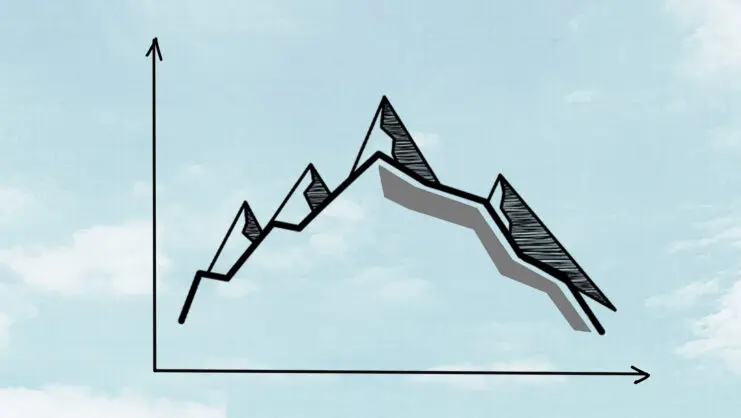

Economic theory holds that negative inflation leads to low nominal interest rates, which can be negative in real terms. For indebted economic agents, whose loans tend to be variable-rate, a drop in interest rates is generally good news. In contrast, when the rates are negative in real terms, the yield is too low for those who save, leading them to change their investment mix, switching from deposits to funds, or to seek out new countries with more profitable currencies. The reduction in savings in the less profitable currency leads to a fall in productive investment. At the same time, the assumption that goods and services will be cheaper in real terms down the line discourages consumption, which can trigger a downward spiral affecting wages or, more often, employment.

To prevent this situation, there is an inflation rate that results in an equilibrium real rate of return or interest rate, which generates enough demand to bring about balance between saving and investment. Zero or negative inflation is not conducive to achieving an equilibrium real interest rate, since nominal interest rates usually have a minimum floor of zero. The imbalance between demand and production, which cannot be prevented through a negative equilibrium real interest rate, leads to a drop in employment and wages, which further weakens demand and causes deflation.

The assumption that goods and services will be cheaper in real terms down the line discourages consumption, which can trigger a downward spiral affecting wages or, more often, employment.

When an economic recession coincides with a high level of financial leverage, deflation can be even more challenging, resulting in a downward spiral. The decline in prices, wages, and income increases the real value of debt, forcing borrowers to reduce spending and consumption in order to repay their loans, which exacerbates the recession.

To break this vicious circle, measures should be taken to promote the recovery of demand, such as those designed to facilitate increased production of goods and services at lower cost, which would boost consumers’ real income and, thus, stimulate demand. It would also be beneficial to implement looser fiscal policies in order to increase cash flow after taxes, although this does not seem very viable in economic environments such as those of the eurozone countries.

Expectations are key to emerging from the crisis. It is thus understandable that the economic authorities prefer to talk not about deflation, but rather the low inflation caused by temporary factors, such as the dramatic decline in oil prices. However, the only way to build confidence is to fulfill promises, which must thus be aligned with realistic growth targets.

For private debtors, deflation or low inflation has the positive consequence of reducing real interest rates and increasing disposable income. On the opposite side of the scale, it pushes down wages, worsens the debt ratio, and reduces gross worth. Without inflation, household assets, especially homes, are unlikely to increase in value. Therefore, households’ net worth (what they own less what they owe) does not usually increase as a result of inflation, unlike in situations of rising prices. In a context of falling property values, such as Spain in recent years, many families can end up owing more than the market value of their gross estate, resulting in what is technically known as negative equity.

Meanwhile, families that are not indebted and have investments in financial assets benefit from the potential rise in rates in real terms and a reduction in their tax burden, although they are hit by the reduction in nominal rates.

Expectations are key to emerging from the crisis. It is thus understandable that the economic authorities prefer to talk not about deflation, but rather the low inflation caused by temporary factors.

Opening of foreign markets

For non-financial companies, the benefits lie in the opening of foreign markets through increased exports, especially when domestic demand is in recession. However, turning to exports to maintain cash flows can have mixed effects, as it gives rise to new risks, associated with exchange rates and the countries in which the investments are made. In this context, it becomes more important for such companies to have an appropriate capital structure. Negative effects would include the need for operational and financial restructuring.

Deflation allows banks to restore their financial margin by providing services and requires them to become more efficient. The negative effects mainly consist of the reduction in net interest income and the increase in delinquency. In this context, most banks follow a strategy of increasing fees, i.e., of charging for banking services and promoting business such as cards or investment funds. In the current environment of declining rates, some financial institutions have chosen to purchase public debt portfolios primarily financed with money from the central bank. Technically, this activity, referred to as the ALCO portfolio, is a kind of carry trade, since the interest earned on the public debt is higher than that paid to the central bank for the provided funds.

Very low-rate environments can also deeply affect insurance companies, especially the life insurance segment, where commitments are met through fixed-income portfolios. Sometimes these commitments are not fully covered by future cash flows from the bonds in the portfolio, and reductions in interest rates can significantly reduce both financial income and profit.

Deflation can likewise pose a significant problem for investment funds that invest in monetary assets, as management fees can outstrip the interest on the portfolio, requiring the manager to reduce them, sometimes to almost zero percent. With high-risk products, anything else would expose the client to negative returns.

In the current environment of declining rates, some financial institutions have chosen to purchase public debt portfolios primarily financed with money from the central bank.

Bond yields

Guaranteed funds are a curious case. They are typically built by buying a zero coupon bond and a call option. Basically, the bond yield ensures the capital protection, and the “extra” return the bond offers on the invested capital is used to pay the option premium. In a context of very low interest rates, bond yields can be so small that it becomes impossible to launch products that guarantee 100% of the principal, leading many institutions to turn instead to products offering partial guarantees (e.g., 80%).

Generally speaking, the governments of OECD countries tend to be highly leveraged. Therefore, lower nominal interest rates mean they pay less for new public debt issues, reducing the financial burdens. This situation brings relief, but only apparently. Debt sustainability is conventionally measured as the ratio of public debt to nominal GDP, i.e., the market value of the goods and services produced. This ratio is considered suitable for measuring the sustainability of public debt (i.e., the ability to pay it), as it compares public debt to the current market value of the goods and services a country produces, and ultimately a country’s income (basically, through taxes) is entirely conditioned by its nominal GDP. In a deflationary environment, nominal rates are low, which helps to control the public deficit and, therefore, public debt. However, the decline in prices also prevents nominal GDP growth. Thus, a context of low inflation (or, worse yet, deflation) coupled with an economic crisis renders the public debt unsustainable, even if the public deficit is under control. In short, repaying long-term public debt requires two almost essential components: economic growth and a little inflation. In their absence, debt becomes very difficult to repay.

© IE Insights.