Some of the reasons why feedback fails are well understood: weak structure, few supporting examples, non-empathic messaging, poor timing, etc. Two other factors are equally important but less widely recognized: a failure to match the feedback to the circumstances and an overly serious delivery that shuts down the recipient’s ability to learn.

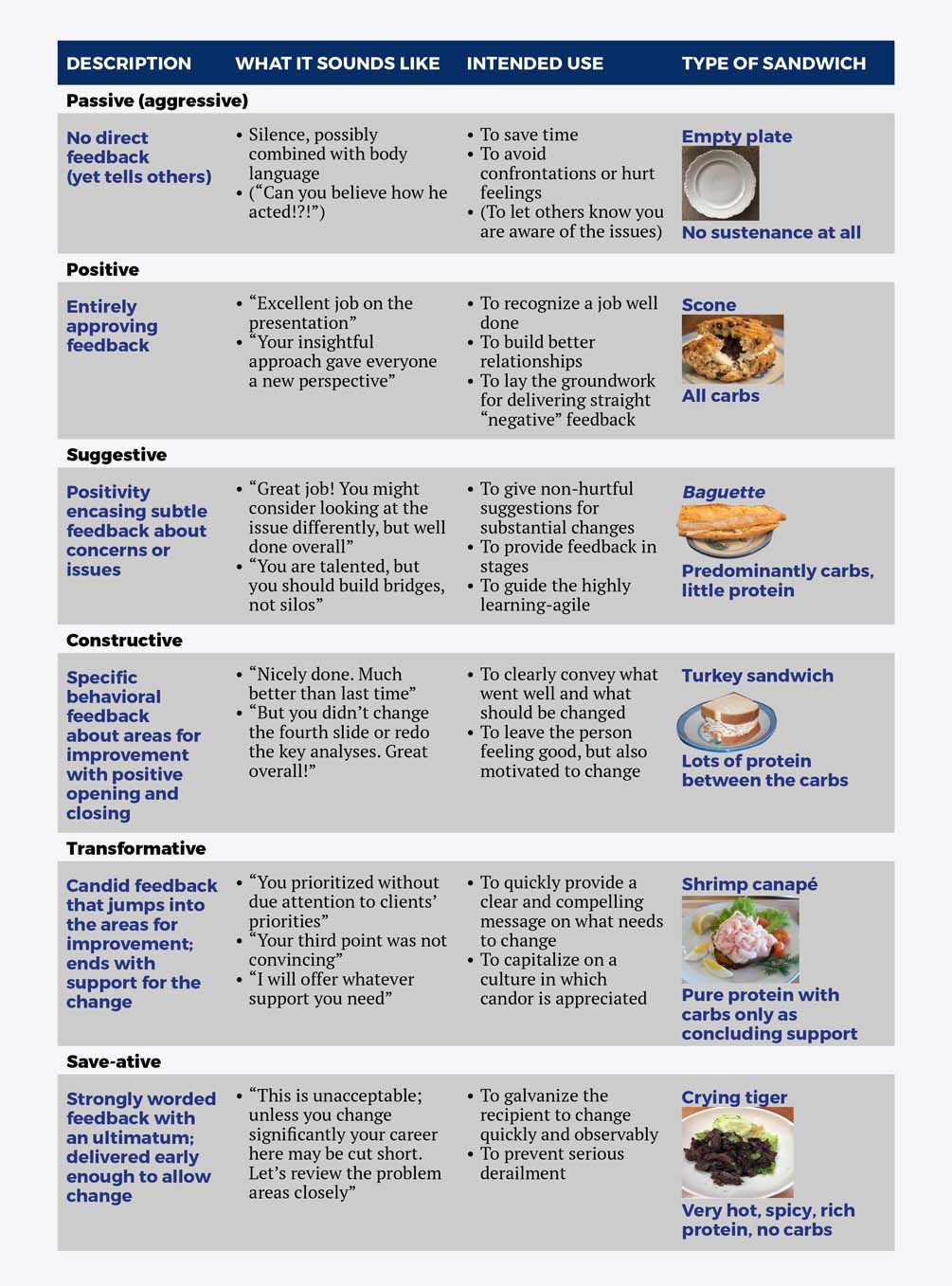

To address these challenges, we have developed a model that helps managers adjust the context and tone of their feedback. Think of it as a buffet offering six types of feedback, each represented by a type of sandwich. On this menu, the protein filling is the constructive feedback and the carbohydrates are the positive messaging.

The perils of serving up the wrong sandwich

If you provide largely passive feedback—which isn’t really feedback at all—your people are unlikely to grow. Thus, you do them a disservice as a manager. Our research shows that recipients want almost 20 times as much feedback as they get.

If you do not give positive feedback, you are less likely to encourage good behavior and strengthen the recipient’s self-confidence. You also decrease your chances of building a relationship or establishing the necessary trust for your negative feedback to be well received.

Suggestive feedback is particularly dangerous. Managers may think they have conveyed the message, but the recipients often barely hear it—or even hear the opposite. Thus, they continue their frustrating behavior, while others become more irate. This type of feedback is not specific enough for people to understand what they should actually change, nor is it arousing enough to propel someone into doing the necessary hard work.

The trouble with constructive feedback is that people think the associated positive feedback is window dressing included only to soften the blow. So, they disregard it even though it actually is bona-fide feedback.

Transformative feedback frequently does not hit the mark due to wording and tone. It is often delivered when the provider is emotional, if not exasperated. The message therefore comes across more negatively, and less supportively, than intended.

The typical hazard with save-ative (“or else!”) feedback is not giving it early enough to prevent derailment.

If you do not give positive feedback, you are less likely to encourage good behavior and strengthen the recipient’s self-confidence.

Recommendations

These dangers can be avoided by selecting feedback type circumstantially. A situational feedback model enables you to make choices about what sort of feedback to provide in different situations depending on the goal, severity, learner openness to personal change, and unit culture.

1. Heighten your awareness

- Become more self-aware. One way of doing this is to distribute 100 points among the six categories, according to the relative proportion of types of feedback you generally provide. Reflect on the changes you might make to deploy a more situational approach. Then ask your typical feedback recipients to do the same exercise for you. Notice the ways in which their perception differs from yours.

- Adapt to each individual. To improve your results, ask your feedback recipients to repeat the aforementioned distribution in terms of what they would find most helpful. Look for ways to make the changes each person wants.

- Consider the context. Reflect on all the comments you have received to determine whether your personal distribution is culturally aligned. If there is significant misalignment, make whatever changes are appropriate.

2. Optimize

- Catch them doing it right. Unless you already give a lot of positive feedback, you should give much more on a regular basis. (The ideal ratio is 6:1.) Also, serve only scones in group situations, reserving the other sandwiches for private conversations.

- Don’t beat around the bush. Ensure that all of your feedback is direct, specific, and behavioral. Then check that the message has been heard as intended and accepted.

- Give options. When providing constructive feedback, ask whether the recipient would prefer to hear the positive or constructive observations first—mentioning that both are genuine and valuable.

- Watch your words and tone. Even high performers, who generally welcome improvement feedback, are sensitive to how it is delivered.

- Don’t wait until the 11th hour. Be sure to provide SOS feedback well before it’s too late.

3. Decrease anxiety

- Avoid trauma. To reduce the stigma of feedback and make the exchange more natural, integrate the sandwich language. Tell stories, use analogies, lighten up. Instead of asking “Would you like some feedback?”—a question that inspires terror in the souls of most people—ask if they are in the mood for some turkey or shrimp.

- Spread the model. When everyone feels comfortable using this terminology, the quality of feedback will improve and the associated angst will abate considerably.

A situational feedback model enables you to make choices about what sort of feedback to provide in different situations.

Some parting thoughts

- Adjust to the situation. Decide what sort of feedback to provide in each situation according to your goal, the severity of the problem, learner openness to personal change, and the unit culture.

- Continuously improve. After each feedback interaction, review what you did and decide whether you used the right approach. Use what you learned to become more effective in future situations.

- Make no excuses. Most people want—and need—feedback. Deliver on your leadership accountability! Follow the advice of the New York City subway system: “If you see something, say something.”

Be intentionally versatile and remember that feedback is the lunch of learners. Don’t let them go hungry.

This article represents the authors’ personal opinions and not those of their employers or affiliated organizations.

© IE Insights.