In both personal and corporate spheres, lifeblood is not enough, even when it is infused with wisdom. Countless grand projects and promising leaders—both contemporary and historic—have been thwarted or undermined by inept communication. Companies are like people: they think, they feel, they dream, they grow, they get sick, and if they don’t get better, they die. Having problems isn’t bad in itself, but not solving them is.

To communicate, first and foremost, you must listen to understand, not to reply. Another important point is that lying—in the strictest sense of the term—cheapens communication. And finally, the more connected you are with the outside world, the less connected you are with your inner world. Here’s a concept that applies to all organizations: even the best communication cannot make up for bad management, and the worst communication discredits the people in charge. Bad communication exacerbates bad governance, but the best communication can strengthen it.

Through internal communication, organizations either energize or infect their environment, their corporate soul. Neglecting the people on the inside—being careless with internal communication—can cause an infection that leads to new diseases and aggravates existing conditions. Early detection increases the effectiveness of the treatment.

In both personal and corporate spheres, to communicate you must start by listening to understand, not to reply.

Listen, be, and convey

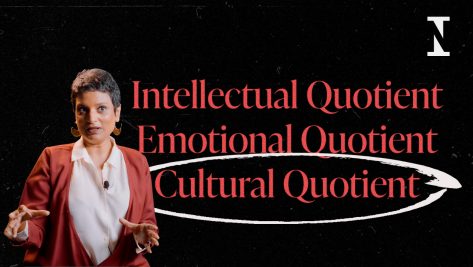

Communicating with executive verbs like listen, be and convey is inseparable from today’s notions of management. Listen is the mother of all communication verbs. Although now somewhat diminished by widespread rhetorical use and diffuse practical implementation, it is striking to see the broad application of the verb listen in digital environments despite the dwindling use of this particular action in the personal realm, where conversations are postponed, shortened, hurried, interrupted, and noisy.

The verb listen goes hand in hand with a noun: humility. A humble person has his feet on the ground, is in touch with reality, and—for this very reason—is committed to changing it for the better. Humility allows you to learn—which can only be done by listening, not speaking—and makes your mind more agile, open to positive developments (progress), and able to identify negative practices (regression).

The only effective verb-noun combination is listen with humility. Practitioners of this executive communication style strengthen their position of leadership because they develop skills such as learning, demanding, motivating, apologizing, correcting oneself, and even growing. This management style gives rise to a key capability: managing perceptions. Through the mere act of listening with humility, you are able to see that a single reality (data) can be perceived differently by different people, depending on the context and their emotions. If you manage a company or institution without listening with humility, you are guaranteed to encounter avoidable conflicts and face significant losses of time, energy, engagement, and therefore money.

The second executive verb is be. Although it is an unsophisticated verb, it has a great deal of value compared to its debased imitator: seem. In both personal and corporate communication, it’s easy to mistake one for the other, especially when you don’t start by listening with humility. The adjective that goes with be is true. Truth forms the basis of genuine communication and often falls victim to environments tainted by appearances that conceal wretchedness. We are all wretched in one way or another, so we mustn’t deny it, but we also shouldn’t magnify it recklessly.

Transparency doesn’t mean baring your soul; it means showing the right things to those who deserve it. The aforementioned ability to manage perceptions provides some interesting guidelines with regard to transparency. In communication, the decisive factor is not what the management says, but what others perceive and interpret.

The last of the three executive verbs is convey. Many people see this as the essence of communication and decisive action. I don’t deny the importance of speaking, but I insist that it is most effective when it comes after—not before—listening with humility and being true. I think this sequence is conceptually logical and also effective from a business perspective.

The noun that goes with convey is consistency. Once the first two verbs have been properly applied, consistency is perceived as such by those who feel that they have been heard and have seen for themselves that the message is true.

Leaders of the past knew how to talk; leaders of the future base their eloquence on empathetic listening, which requires high doses of passion for people and a commitment to reality.

Credibility is based on deeds

With the listen-be-convey process, credible messages can be delivered with little effort because they merely serve to confirm what people already perceive. Credibility is derived not from words but from deeds, so you needn’t—and shouldn’t—convey a large number of messages. Among other reasons, too many messages make for dispersed content.

Some organizations sacrifice the truth to preserve the good. They disguise or conceal official facts and data, with the admirable goal of preventing employees from becoming discouraged. By doing this, however, executives reveal their incompetence and immaturity, as well as the myopia of their sensitivity. In this communicative pathology, your deeds show—although you may deny it—that you believe the ends justify the means. In the best-case scenario, silence and denials work only in the very short term.

Some executives wonder what they should do to stop people from thinking that they are inconsistent, unfair, and incompetent. Well, they should start by not being those things. Even the best communication cannot make up for the worst reality, although it can modify our perception of it. Manipulation—a tactic as old as humanity itself—is a tempting option that can be very effective in mediocre, inbred, self-satisfied environments. The only way to improve is to change, but not all changes are for the better, nor are they automatically noticed, especially if the transformation sought is profound. Changing for the better requires thought, and thinking is incompatible with increasing speed and mental dispersion.

New things aren’t good just because they are new, but because they are good. Likewise, old things aren’t bad just because they are old, but because they are bad. The key is to look not at the clock but at the compass. Communication is not about knowing many languages but about contributing or learning something.

Leaders of the past knew how to talk; leaders of the future base their eloquence on empathetic listening, which requires high doses of passion for people and a commitment to reality. This attitude has an immediate healing effect on team members (who are motivated by knowing and feeling that they have been heard and probably understood), on the organization (problems are detected that would otherwise be disregarded and left unresolved), and on the leader (whose internal prestige grows and spreads).

Communication has something in common with the exercise of power: its effectiveness is based more on authority (leading) than on clout (giving orders). If you are what you say you are, you have nothing to worry about. But if you’re inconsistent, no words can sustainably convey something that you are not. Credibility is like prestige—you can’t confer it on yourself; others must decide that you deserve it.

Here, it is useful to recall Franz Kafka’s words to his father: “You, so tremendously the authoritative man, did not keep the commandments you imposed on me.” It seems that Kafka’s father began his intended communication with the verb convey, but did so inconsistently.

The fact that convey occupies third place on the podium of executive verbs does not mean that it is any less important. Conveying a message well can be the final flourish in an exemplary communication process, but it can also be the opposite. If, after listening and being what you say you are, you don’t convey the message well, your previous achievements will have been in vain.

Credibility is like prestige—you can’t confer it on yourself; others must decide that you deserve it.

Crisis situations

Foreseeing the foreseeable and sharing whatever you can will keep you on the right path of executive communication and help you go from KO to OK in crisis situations. If you failed to engage in preventive communication before a round of layoffs, for example, here’s what you need to do now: call your people together, look them in the eye, apologize, and do something positive: help them find another job, provide fair severance packages, etc. This sort of genuine communicative action can’t change the past, but it can change the future.

Just as the mere company of people doesn’t necessarily alleviate loneliness, information overload can leave us feeling isolated. Sending messages, publishing newsletters, providing suggestion boxes, calling meetings, canvassing the social networks… All this is for naught if people don’t hear what they want to know, what they need to know, and what they should know. It’s like having a pharmacy stocked with every drug for every possible disease, but not having the advice of an expert who knows which one to prescribe.

Just as ethics shouldn’t be considered a bonus in business management, it should come as no surprise that lifeblood imparts wisdom, or that top executives in any field need to have basic communication skills. From the fertile fusion of communication and management, in the early 21st century I developed the concept of communicagement, which translates, roughly, to “manage by communicating.”

© IE Insights.