Hurricane Harvey made landfall on the coast of Houston, Texas in August 2017 and Hurricane Irma followed in September, hitting southern Florida. These two hurricanes, which rank in the top five of the costliest storms on record in the United States, destroyed thousands of homes by flooding and/or strong winds. While major hurricanes with the potential to cause severe economic damage and a wave of mortgage defaults is not a new phenomenon, climate change is expected to bring about such catastrophes more frequently in the near future.

Yet, even as climate change continues to take its toll on the planet, people continue to buy homes in the United States in areas that are in direct line of flooding, fires, and extreme weather patterns. Destructive hurricanes, for example, endanger the many homes and businesses that dot numerous coastal areas in the U.S.

The U.S. has a new financial market that trades specifically on the risk of mortgage default (called Credit Risk Transfers) and the emergence of this new market demands further investigation into the effect of climate risk on mortgage pricing. How much is a home worth when it is subject to climate risk, and how much are Americans willing to pay for that home? What responsibility should the banks take in the lending of money for this purchase?

My colleagues Athena Tsouderou and Susan M. Wachter and I studied the Credit Risk Transfer market during a period of stress caused by these two hurricanes, Harvey and Irma, measuring how the investors who buy these securities price the credit risk in U.S. mortgages absent of government intervention. That is, we looked at how much compensation the investors demanded for taking on the risk of mortgage defaults exposed to climate change risk.

The current mortgage system encourages household exposure to climate because it prevents homebuyers from actively considering the hurricane risk of the homes they purchase. But, on a positive note, the U.S. housing system achieves a powerful macroeconomic policy that lowers costs of mortgage credit in a crisis. For example, in the first quarter of the COVID-19 crisis, the cost of mortgage credit would have been 21% higher if the private market – and not the U.S. government – was taking on the credit risk. Thus, our paper contributes to two active debates: financial consequences of climate risk, and how to reform the U.S. housing finance system.

The housing system in the U.S. is unique in design in that the majority of the mortgage credit risk is borne, either directly or indirectly, by the government. That is, private lenders originate mortgages but if these mortgages default the credit losses are covered by the U.S. taxpayers. This system started after World War II in order to promote affordable long-term mortgages and it is now based on three institutions: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae (the latter being a government agency since its inception.)

Fannie and Freddie, usually called the Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), began as private corporations that enjoyed a government assurance on liabilities, specifically the government guaranteed that the GSEs would honor their debts. Their primary business is to buy the mortgages that lenders originally offer to U.S. households, pack them into bonds called Mortgage Backed Securities, and sell these bonds to investors in financial markets under the condition that, if the mortgages default, the GSEs would cover the losses. To make such an activity profitable, the GSEs ask the mortgage lenders to charge homebuyers with an upfront insurance premium (called the guarantee-fee, or simply g-fee.) It is not mandatory for the lenders to add this fee to the mortgage but it is if they want the GSEs to buy and insure the credit risk of the mortgages, and thus the majority of lenders – if not all – tack on the extra g-fee.

The GSEs were profitable in normal times with low rates of mortgage default. However, they could not survive the wave of defaults that came with the global financial crisis that started in 2007 – the g-fees were simply not enough to cover the credit losses. Thus, in 2008 the U.S. government basically nationalized the GSEs by putting them into “conservatorship” and the GSEs became, in practice, two more government entities. Thus, all mortgage credit risk nowadays is borne by the U.S. government. Many people did not consider this is an optimal situation since it exposes taxpayers to possible large losses in the event of another default wave, so the U.S. government created a new market (the Credit Risk Transfers or CRT) in 2013 to experiment with transitioning towards a new model in which private capital assumes the credit risk.

In this CRT market, the GSEs (now essentially the U.S. government, since the GSEs are in conservatorship) sell securities with payments that depend on whether a set of underlying mortgages default or not. By selling the CRTs, the GSEs collect revenue. If there is no default in the underlying mortgages, the GSEs make payments to the investors who now own the CRTs. If the mortgages default, it is the investors who suffer the losses. Thus, the GSEs have successfully transferred the credit risk of the CRTs to private investors.

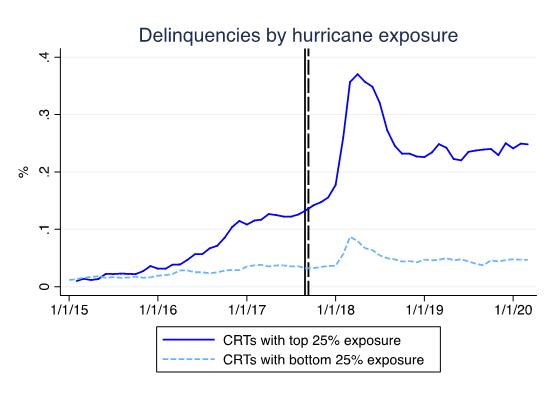

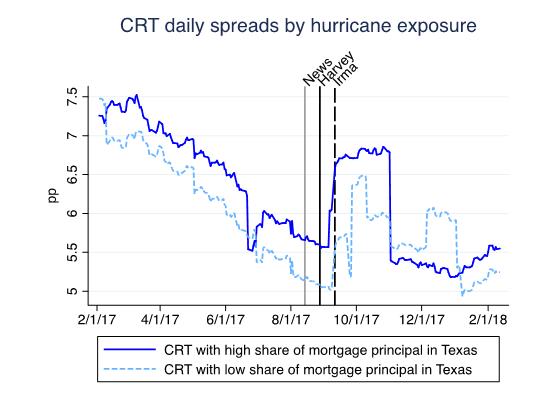

In our research, we developed simulations that enable the study of the impact of destructive hurricanes on the CRT market. We chose Harvey and Irma because they were both unexpected and severe. These two hurricanes were the first major shocks that increased the risk of mortgage defaults for the CRT market and, moreover, they were shocks to the local market. This second point is important because it shows that not all CRTs are affected by hurricanes (or other instances of extreme weather) to the same degree. Severity is based, to some degree, on locality. The more the homes were exposed to the brunt of Harvey or Irma, the more affected were the CRTs, thus making possible the study of how the arrival of the hurricanes impacted CRT securities pricing.

Investors ask for roughly 10% additional compensation when buying those CRTs with more exposure to hurricanes, which makes sense because the securities with these mortgages are more likely to suffer defaults and thus investors will more likely lose money. This is the first time we have been able to measure how much climate risk can stress markets and moreover, we are now able to quantify just how much mortgage rates would change if the government stopped absorbing credit risk and was replaced by private markets.

By detailing precise estimates on how market-determined mortgage rates will react when exposed to risk of default our research provides several insights important for policymakers:

First, under the current system that has the U.S. government absorbing all credit risk, geographical differences in mortgage cost are muted. Thus, there is no incentive against settling down in hurricane-exposed locations. In fact, the current system encourages climate risk taking because people pay the same mortgage costs for a home that has all the lifestyle benefits of living near the coast (it just might get destroyed by a hurricane) as they would for a home in a safer region. Mortgage prices do not help homebuyers understand hurricane risk.

Second, the government absorbing credit risk is a powerful macroeconomic policy to help with recessions, just like fiscal or monetary policy. We determined this by calibrating our model to match the empirical estimates from the hurricanes and measure the stimulus provided by those government guarantees that absorb other credit risks. For example, the COVID-19 crisis has, so far, increased mortgage defaults by 114% – but without the government guarantees, the cost of mortgage credit would have been an additional 21% higher. Higher cost of credit turns into lower home prices, less construction, less wealth, and higher unemployment.

In the optimal mortgage system, government guarantees to mortgage credit risk would not be removed completely – though the optimal level of intervention warrants further investigation. It is also important to note that, in the absence of government intervention, inequalities in access to credit will increase because the guarantees help the riskier households, those that are usually low-income (Gete and Zecchetto 2018).

Ideally, a U.S. mortgage system can be established that does not overexpose households and taxpayers to climate risk while helping the economy to navigate crisis times and promote affordability. This is the only way forward in a world that will, in all likelihood, be battling the effects of climate change for the foreseeable future.

Figure 1 – Delinquencies (delayed payments for more than 120 days) for CRT mortgage pools that had the highest and lowest geographical exposures to the hurricane-hit areas. The solid vertical line indicates August 28, 2017, which is the first trading day after Hurricane Harvey’s landfall in Texas. The dashed vertical line is September 11, 2017, which is the first trading day after Hurricane Irma’s first landfall in Florida.

Figure 2 – Daily spread (yield to maturity minus one month U.S. Dollar Libor) in the secondary market of two CRTs that only differ in their geographical concentration to Texas. The first CRT’s original principal balance was located 7.03% in Texas, and 5.48% in Florida, whereas the other CRT’s was 3.62% in Texas, and 2.78% in Florida. These CRTs from Freddie Mac were issued in the second quarter of 2015, they have the same original term to maturity, they are linked to the most junior tranche, and they have LTV average ratios of 76% and 74% respectively. The first solid vertical line indicates August 15, 2017, when the first warnings about Harvey came out. The second solid vertical line indicates August 28, 2017, which is the trading day after Harvey’s landfall, and the dashed vertical line is September 11, 2017, which is the first trading day after Irma’s landfall.

© IE Insights.