Most organizations now find themselves in a multiproject scenario, even though they were created to handle only a single-project scenario. The critical-chain project-management methodology, developed by Israeli physicist Eliyahu M. Goldratt, proposes a solution for operations management in multiproject scenarios. This solution acknowledges that in order to manage uncertainty it is necessary to share—not distribute—resources. Goldratt therefore introduced buffers and time sharing, concepts derived from his theory of constraints.

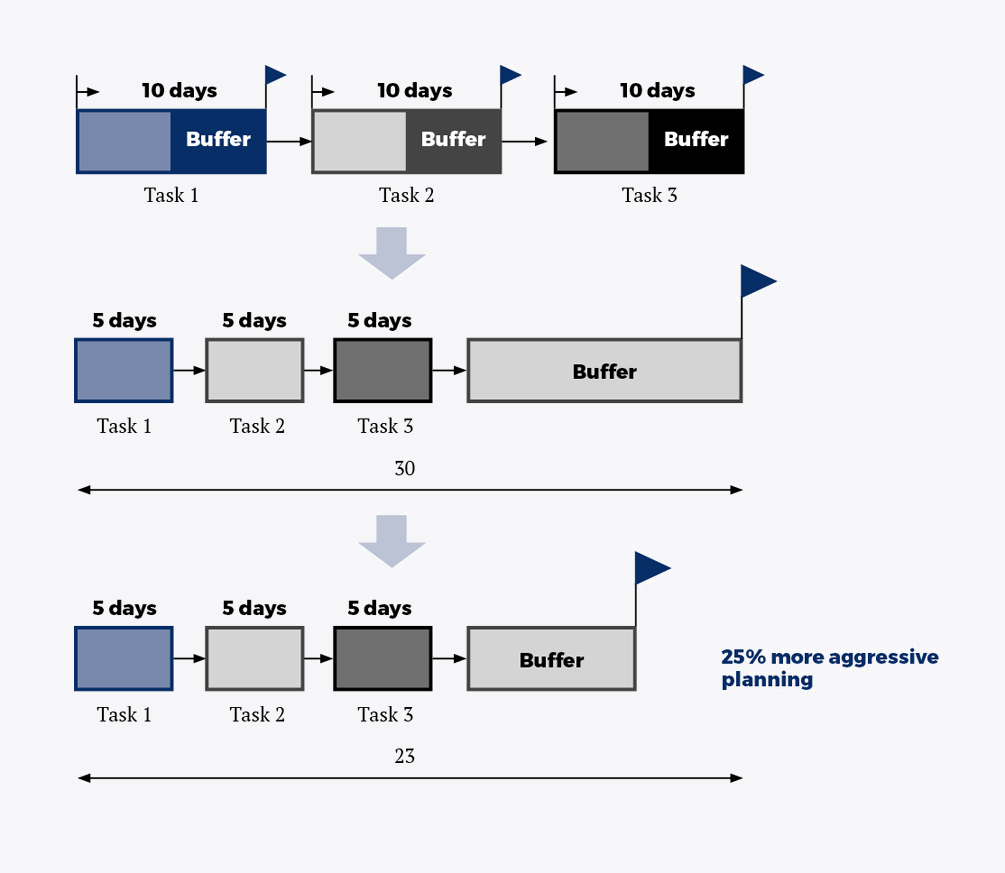

With critical-chain project management, Goldratt proposed an approach that downplays planning in favor of execution. This approach abandons the classical static planning model that manages and justifies deviations in favor of a new model in which plans are revisited every day in light of the remaining task duration, i.e. the time needed to finish the project. With this methodology, you start later in order to finish earlier. This disruptive concept contradicts all the classical theories that have always been applied.

The only thing that matters is the remaining duration, not the progress made so far.

Upgrading from map to GPS

What determines how long it takes you to drive somewhere? Neither your skills behind the wheel nor your car, but the traffic on the road. In a project, the traffic is all the tasks that are currently open, and for a given journey you might take ten minutes or an hour depending on the amount of traffic. The difference in travel time is due to the number of waits you encounter, which has to do with the number of open tasks. This is the opposite of what most companies do, because they prefer to have lots of traffic in order to keep people active. But the more projects you have open, the worse things get.

Buffers and critical-chain project management are like a GPS that can recalculate your route and priorities every day. When it comes time to make a decision, it classifies tasks by importance. As a result, the planning is based not on intermediate milestones but on buffers, allowing the organization to recalculate its plans on a daily basis as a function of the actual remaining duration of the tasks in progress.

Planning with intermediate milestones is like a printed map that becomes useless once you make a wrong turn, whereas a buffer is a mechanism for managing an entire project that shows the impact of any deviation on the project as a whole.

The solution, therefore, is to implement ideas or mechanisms for managing the execution, not planning and control. Planning accounts for 10% of the impact; the other 90% consists of ideas and rules for execution management, rather than detailed plans.

The only thing that matters is the remaining duration, not the progress made so far. The amount of unfinished work will be different tomorrow from what it is today, and this is the only real fact: at the end of each day, the people working on each task must declare how much is left to do. This information is more real than any plan. The recommended buffer length is one third of the turnaround time.

The weakest link

According to Goldratt’s theory of constraints, a project or organization is like a chain made up of various links. If you subject it to a tensile test, it will always break at the weakest link. Therefore, it is completely useless to strengthen any other link besides the weakest one.

Translated into multiproject terms, the weakest link is a department and, in general, when the work is intellectual in nature, the weakest link is not a resource but problem-solving capacity. In a chain, the important thing is the relationships and synchronization between the links, not the links themselves—except the weakest one.

Costs are like the weight of the chain. If you reduce the cost of several departments, you reduce the organization’s overall costs. However, when it comes to speed and synchronization, the sum rule doesn’t apply because there’s only one link you need to improve: the weakest one.

The problem is synchronization, since a project takes at least a month and multiple departments must be aligned. The critical-chain method applies to each individual project. When you have multiple projects, you have to identify the synchronizing resource: the drum.

When it comes to speed and synchronization, the sum rule doesn’t apply because there’s only one link you need to improve: the weakest one.

Changes and conflicts of interest

Even if a project is well defined, some change in scope always comes about at the behest of either an internal department or a customer. At the same time, interactions are continuous and unexpected new tasks can crop up, or there may be changes in sequence or duration, delays, changes in resource requirements, and so on.

Resource leveling is more complicated in a multiproject scenario because many projects are underway at the same time. Some people argue that you need to have a clear idea of the demand, balance it with the load, and make decisions on that basis, but demand is uncertain and changes constantly. Other companies focus on trying to forecast sales with great precision so that they can get the right product to the right place, but this is difficult or impossible to do. What’s more, there is a cascading effect among projects because a single expert may be working on several projects. If one of these projects is delayed, it will affect the others. Similarly, replanning is constant: you try to stick to the plan, but the plan ends up changing as you go along.

Even with well-leveled multiproject planning, any deviation causes load spikes and conflicts. Similarly, there can be multitasking—individual or organizational—which means starting one activity and then another, before finishing the first. The task that has been started continues to consume resources even if no one is working on it, and meanwhile its turnaround time—or that of the project as a whole—increases. The tendency is to start projects as soon as possible, causing everything to slow down and harming the organization.

Many companies choose to hire more people, give them more work hours, and use a sophisticated system to micromanage everyone’s efforts. It is assumed that greater detail decreases uncertainty, but this is false: the uncertainty remains the same.

Other companies decide to put all their effort into planning and invest in the most innovative planning methodologies, but everything can still change in a matter of days.

You try to stick to the plan, but the plan ends up changing as you go along.

Waits

Goldratt understood that project synchronization involves two types of waits: either the resource waits for the task or the task waits for the resource. Waits and interruptions account for nearly half the duration of a project.

Projects can be sped up by reducing wait times. Because of uncertainty and dependencies, some waits are natural and cannot be reduced. Others can be prevented through better synchronization. In these cases, Goldratt’s parameters can be applied to improve synchronization. It is important to realize, however, that uncertainty exists and that what we know about detailed planning doesn’t work for synchronization.

Waits can also occur when projects or tasks start without adequate preparation, which is what usually happens 100% of the time. Measurements are another reason, with estimations of measurements and intermediate milestones as objectives. In general, projects are always behind schedule, never ahead, even though—statistically speaking—50% of projects should finish early and 50% late.

A good multiproject management methodology has to take Murphy’s Law into account.

Multiproject scenarios

A new product launch is a multiproject scenario. One example could be the introduction of new products at a brewing company that launches approximately three hundred projects each year. If the container, the type of packaging, or any other aspect is different, it counts as a new project, even if the beer is the same. The average turnaround time is three months and several departments are involved, so they must be synchronized.

Engineering is another example. A large amount of variability is present from the moment an engineer working on a plan is asked how long he needs to finish the job. He doesn’t know; the best he can do is give an estimate. Curiously, as soon as that estimate is added to someone’s spreadsheet or plan, it becomes the evil number that gives the engineer recurring nightmares about what will happen if he doesn’t meet the deadline.

Another example is good equipment maintenance and repair. Iberia uses this methodology for aircraft maintenance, a task that entails a lot of variability. When an aircraft is inspected, the uncertainty about what sort of problem it has is absolute. Then you have to repair it and test that everything works properly. This entire process must be completed in 20 days, because any plane that is in the hangar is not flying and therefore not generating revenue.

Clearly, a good multiproject management methodology has to take Murphy’s Law into account, so planning is not the solution. The more detail you put into your plans, the more resources they consume. Forget about planning; use buffers instead.

If you implement the ideas of the theory of constraints and critical-chain project management, results are practically guaranteed. The challenge is to keep it up and improve year after year.

© IE Insights.