We analyzed the last few annual financial reports from companies in various geographical areas. Some of these companies—like Carrefour and Dia—were more international, while others—like El Corte Inglés, Mercadona, and Eroski—were more local, and each had a different retail value proposition. We then compared the results of this analysis with data from Amazon, which offers a very different range of products and is making forays into the grocery sector. Our conclusion: no matter which country Amazon was competing in and which companies we compared it to, the key factor was not geography but business vision. The future of food retail will be Amaz-ona: a hybrid of Amazon and Mercadona. Why? Because the key is to develop clear proposals and offer more—not fewer—channels.

A battle of channels and offerings

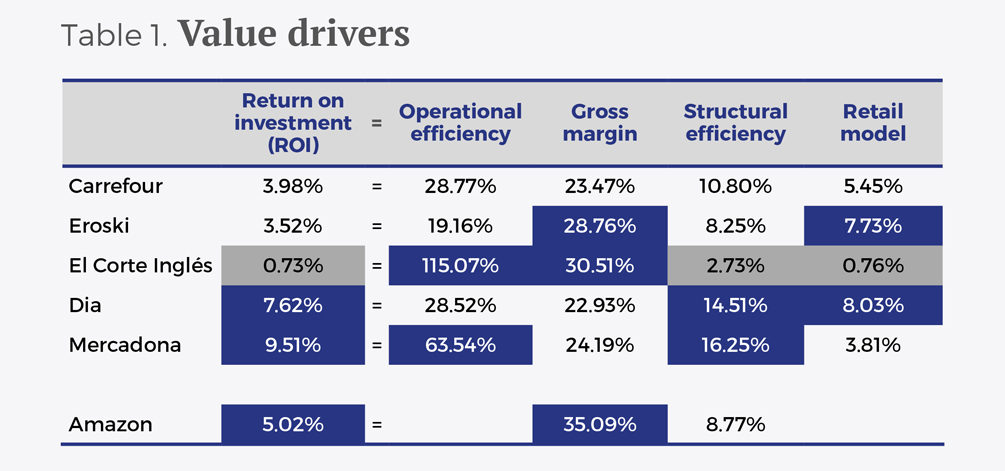

The firms we analyzed differed in terms of product range, geographical presence, size, etc. Nevertheless, if we look at the numbers in relative terms, this analysis can help us make decisions about how we want to compete (see Table 1 for an overview of the value drivers).

We decided to structure our analysis around four variables that represent the key drivers of value in the retail business (naturally, the combination of these four variables determines a company’s health):

- Gross margin: the difference between revenue and cost of goods sold, in relation to sale price.

- Operational efficiency: an indicator that combines the cost per employee and the sales generated by each employee. Operational efficiency increases when average wages are low, but also when there is a relationship between sales and number of employees.

- Structural efficiency: the relationship between a company’s operating profit and gross margin. The higher the value of this indicator, the better the management of the company’s structural costs, especially those associated with personnel, retail premises, maintenance, rent, and management in general.

- Retail model: the relationship between the cost of a company’s points of sale and its total assets. The higher the value of this indicator, the greater the importance of the company’s retail premises in relation to its other assets (for example, stock, investment in logistical infrastructure, etc.).

The most interesting conclusion of our study is that brick-and-mortar supermarkets have a bright future ahead, although the supermarket of tomorrow will be quite different from today’s. You could call it Amaz-ona or Merca-zon, because it will combine the online and offline models. Among traditional firms, those which have a clear model—for example, a strong store brand—will be better positioned to compete in the future. Such is the case of Mercadona, a chain recognized worldwide for its extraordinary store brand. The company’s (very good) profitability is based on its operational efficiency—particularly its high sales per employee—as well as the optimal sizing of its stores in relation to the number of employees assigned to each location.

What happens when we bring Amazon into this analysis? First, a couple facts about the American retail giant: In 2016, Amazon had an overall gross margin of 35%, whereas the average figure for the other chains we analyzed was 26%. As for the efficiency of the companies’ workers and retail establishments, revenue per employee was more than €450,000 at Amazon, compared with an average of €203,000 for the offline businesses. So is everything stacked in Amazon’s favor? Will it win the battle? No, it also has disadvantages:

- It has no salespeople.

- You can’t see its products.

- You can’t take products home with you right away.

Bezos has a clear vision of these problems. He fought to increase Amazon’s revenue from $6.5 billion in 2004 to $107 billion in 2015 by using three commercial antidotes:

- Ratings and reviews.

- Up-to-date photos and information.

- Multiple types of delivery and the development of new stores, plus the acquisition of 460 physical retail outlets (mainly in the United States) through the purchase of Whole Foods.

Rather than forcing customers to use their channels, the companies of the future must force themselves to use the channels that customers prefer.

The Whole Foods deal shows that Amazon—a titan of e-commerce—understands a key idea: if you have more channels, you sell more products. With Whole Foods, Amazon is less than 30 minutes away from practically the entire US population. In other words, rather than forcing customers to use its channels, Amazon has forced itself to use the channels that customers prefer. Amazon’s vision is probably not to become a new Carrefour—a company with numerous “traditional” supermarkets—but rather to combine the best of both worlds.

And this brings us to a final idea: It costs a lot more for Amazon to go offline than for Carrefour to go online. If the Seattle-based retail giant has one thing, it’s cash—and it shows. Amazon shelled out €13 billion to buy Whole Foods (just over 10 times the acquired firm’s EBITDA). Meanwhile, Carrefour recently announced that it would invest €2.8 billion over five years to boost its online activity. In other words, the effort required for Amazon to go offline is much greater than the effort required for a company like Carrefour to expand its online activities.

The key, without a doubt, is to offer more channels, not fewer. Nowadays, stores receive powerful support from the online world, but in a not-too-distant future it might be the other way around. Until then, the model will be Merca-zon, a hybrid that combines the best of Mercadona (well-defined model, very strong store brand, high capillarity, and efficient operations) and Amazon (incontrovertible online capacity, thanks to its antidotes). Who knows? Amazon might decide to buy an affordably priced operator with a strong presence in Europe. One option could be Carrefour, a company whose market value plateaued years ago, but which has a plan for growth based on its store brand. Is there an Ama-four in our future?

© IE Insights.