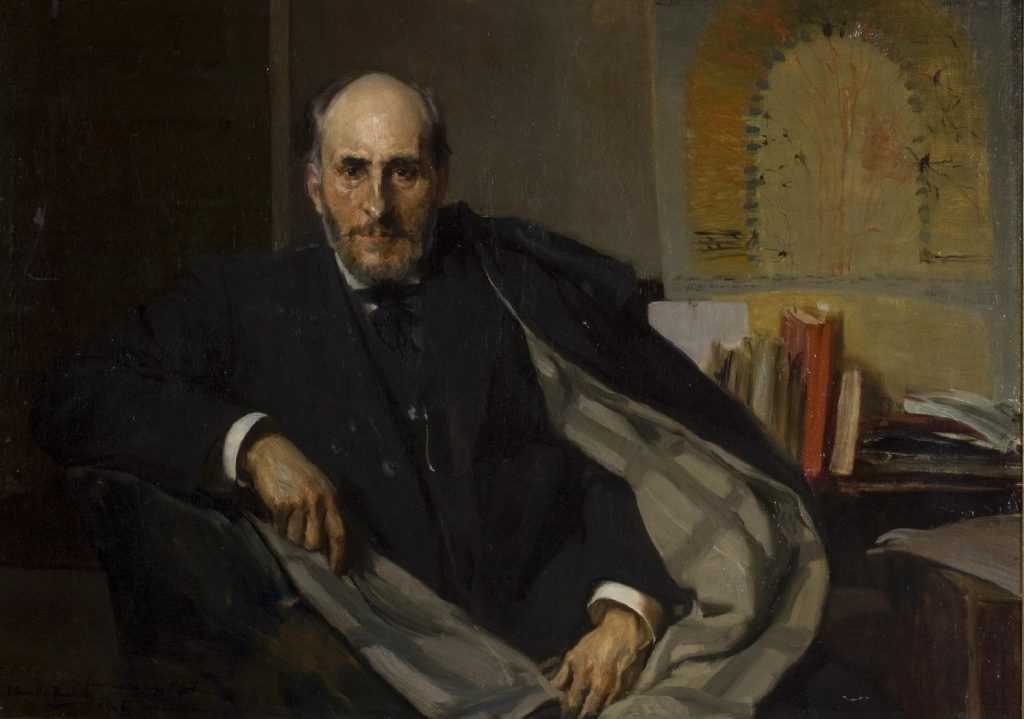

In 1906, the Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla finished a half-length portrait of the newly crowned Nobel laureate: Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Most modern-day museumgoers who are familiar with the Valencian artist know him for his adept ability to capture the Iberian peninsula’s legendary luminosity. However, Sorolla had also earned fame as a portraitist – attracting patronage from a wide range of Restoration Era elites, including King Alfonso XIII and novelist Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. Thus, the “father of neuroscience” could not have asked for a better artist to paint his likeness.

Cajal was Spain’s first Nobel Prize recipient. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in neurohistology – the study of the nervous system through microscopic tissue analysis – alongside Italian scientist Camillo Golgi. Sorolla painted Cajal’s likeness in oil on canvas and in the portrait, Cajal is seated frontally at his desk, positioned close to the picture plane with a slightly turned posture, creating a sense of intimacy with the viewer. His right arm rests on the side of a chair, while his left arm crosses his body, clutching a shawl with a two-tone design – one side solid black and the other in soft grey with crisscrossing stripes – draped around his shoulders to presumably keep warm. He is portrayed outside his laboratory, without his students or scientific equipment. Yet, Sorolla’s painting still reveals the symbiotic, if not outright generative, relationship between the visual arts and brain sciences. Furthermore, it anticipates the enduring value of artistic interpretation in the field of neuroscience, and how these methods are now being used to study an even more enigmatic subject than the brain’s mechanics: aesthetic experience itself.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Joaquin Sorolla (1906)

Sorolla’s decision to portray Cajal without scientific instruments was unconventional. Traditionally, Western portraits employ objects, settings, and costumes as symbols of the sitter’s social identity. In the late nineteenth through the early twentieth century, continental painters often depicted scientific leaders with the tools of their trade, including microscopes, staining jars and slides, scales, Bunsen burners, and chemical glassware (beakers and flasks).

Sorolla had previously painted a portrait of one of Spain’s other leading scientists. Nine years earlier, he executed two works of the psychiatrist Luis Simarro Lacabra, a friend of Cajal. In Dr. Simarro at the Microscope, Simarro operates a microscope with his left hand and takes notes with a pencil with his right. In Research, Simarro sits at a workstation littered with delicate, glass vials containing chemical compounds and behind him stands a group of observing scientists. Both paintings use laboratory equipment to represent Simarro’s scholarly innovations.

Instead of including Cajal’s research tools (which have since been preserved by the Instituto Cajal) in the portrait, Sorolla chooses to prominently feature a semi-schematic drawing of the cerebellum above Cajal’s desk. This neuroanatomical diagram – offset by its warm tones – serves a dual function: it balances the composition opposite Cajal’s head and hints at Sorolla’s own anatomical training. By including this reference to Cajal’s visual practice, Sorolla fulfills his portraitist duty of communicating information about his subject, and by directly referencing a surviving image from Cajal’s lab, he illuminates (quite literally) Cajal’s professional success as a scientific illustrator.

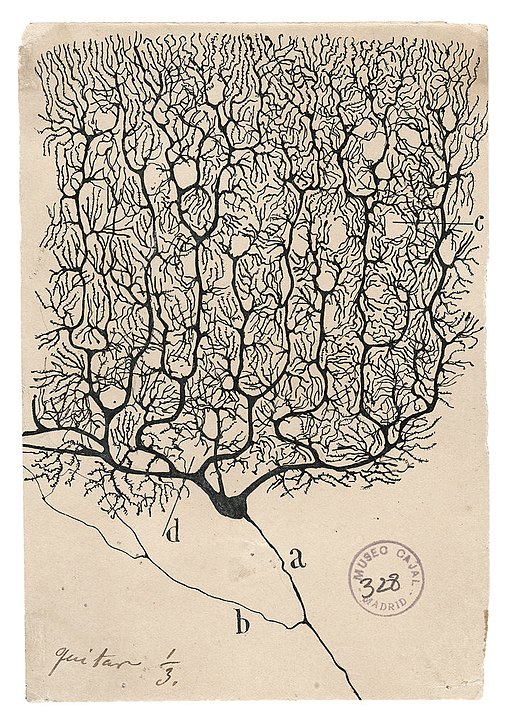

In fact, Cajal’s career is emblematic of the fruitful relationship between the visual arts and neuroscience. His groundbreaking work centered on a painstaking process: observing tissue samples through a microscope and meticulously documenting what he saw with pencil, ink, and paper. These weren’t mere sketches but empirically-derived drawings of the cytoskeleton of neurons and their complex neural networks – works so significant they are now preserved in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. One striking example shows, at the bottom of a beige sheet, a Purkinje neuron, its complicated, branching pathways comprised of axons and dendrites that transmit information.

A Purkinje neuron from the human cerebellum, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, courtesy of the Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid

A Purkinje neuron from the human cerebellum, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, courtesy of the Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid

To create these detailed observations, Cajal used a silver nitrate staining technique pioneered by his fellow Nobel winner Golgi that allowed Cajal to perceive and then visualize neural pathways with unprecedented clarity. His ability to map the structure of the nervous system and to detail microanatomical configurations were innovations that depended as much on the cutting-edge technologies of his era as his ability to employ the most rudimentary tools to effectively visualize information. These drawings remain scientifically relevant today. In addition, their artistic merit has earned them a place in major museum retrospectives, such as the traveling exhibit, The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

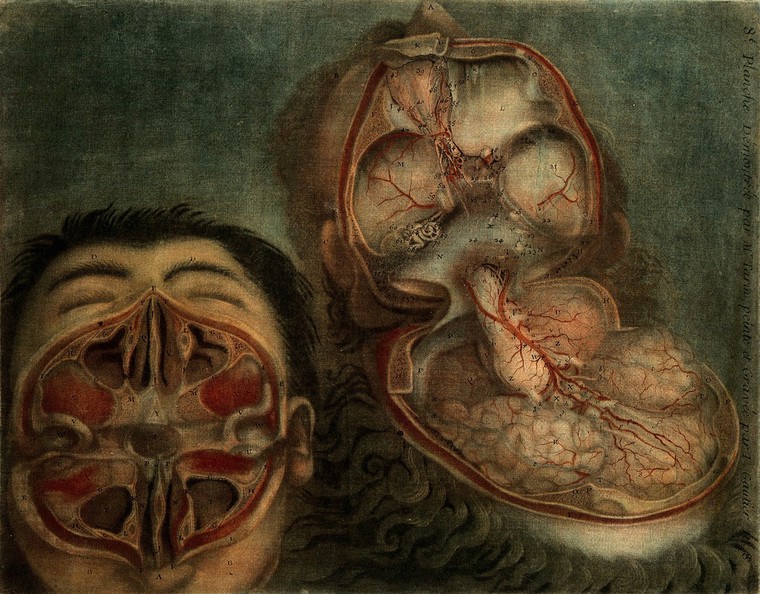

In illustrating his microscopic data, Cajal joined a long line of artist-scientists who likewise advanced our understanding of the brain through visualization. Four centuries earlier, Leonardo da Vinci had applied the growing interest in empiricism to anatomical study, famously recording his observations from dissections with an unrivaled degree of accuracy for the time. A century before Cajal’s intricate neural networks, J.F. Gautier d’Agoty took a different approach with his eighteenth-century mezzotints. These prints presented a sanitized version of anatomy, with one image showing a skull pried open like an oyster shell to reveal the brain like a pearl.

Face and brain: dissections, J.F. Gautier d’Agoty, 1748.

Then, the invention of photography in 1839 ushered in a new era of scientific visualization. During Cajal’s lifetime, the French neurologist Jules Luys exemplified this shift by producing comprehensive medical atlases of the nervous system, using various media to highlight the brain’s anatomical features and pathology. Even a small slide of “coronal segments” showcases how brain visualization has evolved – reflecting changes not just in scientific theories, but also in cultural attitudes and visual communication standards.

By Cajal’s time, brain imaging anatomical structures and biological processes had become standard practice in medical education and diagnosis. His choice to illustrate his findings by hand might seem surprising, given that he worked six decades after the invention of photography and was known to practice photography himself. Furthermore, as historians Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison explain in their book Objectivity, nineteenth-century researchers often preferred the camera over “hand-made” illustrations because of its perceived resistance to human subjectivity. However, Cajal’s hand-drawn illustrations addressed a challenge photography couldn’t solve: capturing the brain’s cellular structure. Early microphotography simply could not register the structural components of neurons – their dendrites and axons – with enough resolution to be useful.

Sorolla’s portrait of Cajal not only alludes to the historical partnership between art and science. It also anticipates the intellectual and technological advancements that were to come. Today’s neuroscientists continue to rely on two-dimensional images, but thanks to advances like fMRI technology, they no longer depend solely on the dissection of tissue to visualize microscopic data. Contrast agents and stains similar to those used by Cajal enable researchers to observe the living brain in action, watching neural activity unfold in real time.

When Cajal investigated neurons, his illustrations became a major interpretative touchstone for neuroscientific theories. A century later, researchers have flipped the script. The very advances that are indebted to Cajal’s findings are now being used to understand something even more elusive than the brain: the creation and consumption of art. For 25 years, interdisciplinary scholars have explored cognitive responses to aesthetic experience under the banner of neuroesthetics, a term coined by Semir Zeki. These researchers seek to connect our appreciation of art to biological mechanisms, studying how external stimuli, from color to sound, trigger neural activity and chemical responses in the brain. Their investigations span from basic visual processing of color and symmetry to the complex emotional responses that art evokes, mapping how neurons fire and pathways form as we engage with artistic works.

Yet, even with our ability to schematize the brain’s operations, how humans relate to art remains remarkably nebulous. Critics of neuroesthetics point out that reducing such complex experiences to biological function fails to account for the diversity of attitudes and tastes and how they evolve over time – not to mention the fundamental question of what counts as “art.” Sorolla’s portrait of Cajal itself illustrates this opacity. In it, he transforms Cajal’s precise neural diagram into an abstraction: a beige semi-ellipse with faint red lines, framed by green daubs of thick, visible brushstrokes and a golden-orange halo.

Although it is unlikely that neither Sorolla nor Cajal considered such scientific illustrations as fine art, Sorolla’s decision to present the diagram in Cajal’s portrait as a painting hung on the wall creates a powerful metaphor. By rendering Cajal’s precise scientific work as deliberately ambiguous, Sorolla reminds us that art, like the mind itself, retains its mystery even as we strive to understand it.

© IE Insights.