In the years to come, we are likely to face two societal challenges in which education will play a leading role. First, the increased importance of automation in labor markets will mean more people compete for employment in a shrinking pool of jobs that are highly productive because they demand fewer people to perform them. Secondly, there will be a need to innovate in order to fill the new and ever-evolving needs of citizens that arise in this global skills oriented labor market.

While the likes of taxation, fiscal profligacy, and trade agreements can positively affect the economic standing of countries, skills development is the only true enabler of long-term success. The primary method for any country to develop and nurture the skills of its citizens is through the education system, from pre-school to university, and then to build on that foundation via on-the-job training and skills transfers between firms.

As we begin to consider the presence of some light at the end of this long COVID tunnel, we must think about the unresolved issues that the world put aside at the beginning of 2020. We must start by re-evaluating the education system.

Primary and Secondary Education

As Nobel Laureate James Heckman has argued, all investment in skills builds on the foundational early years, and thus improving the quality of primary and secondary education is key. Luckily, in regards to primary and secondary education, we can say, with some degree of certainty, that we know the types of broad government interventions that work. For example, developing high quality and affordable pre-school education is essential for improving equity and it is therefore necessary to enable government interventions that ensure that the very best teachers are in the classroom.

But as the world – at large and within our communities – becomes more complex and diverse, so does the learning environment. Education can no longer pretend to be a one-size-fits-all institution. So, how can governments orchestrate widespread reform in this context? The first step lies in greater bottom-up participation, which (like in many areas of policy) is necessary in order to obtain information about the needs of students within a particular community. In the United States, my own research with Paul E. Peterson has highlighted the importance of local (municipal) democratic and financial control in improving outcomes. We found that for every 10 percentage point increase in the local share of a school district’s revenue, student achievement also increases, by up to a third of a year of learning. This suggests that local control of finances, and the involvement of parents and authorities that goes with it, positively impacts student learning.

Although there are always new challenges – and constant technological change will only bring more – the basic playbook is clear: the goal is to educate as many people as possible in a way that prepares them for a productive and promising future, whatever that future might be. Doing so becomes a question of gathering enough sustained political focus and overcoming parochial interests for the greater good.

Higher Education

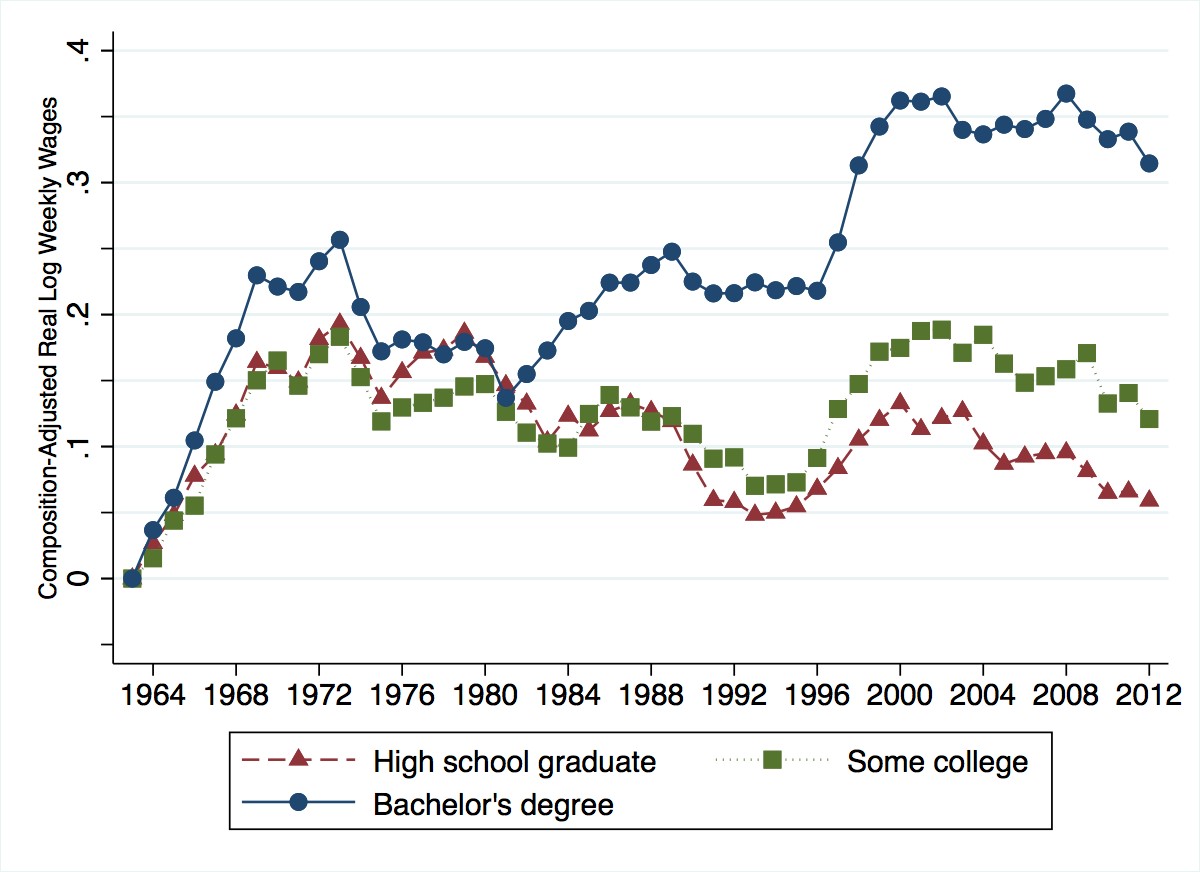

Everywhere, people who graduate from universities earn more. This is known as the college premium and it has increased since the 1950s.

Source: Author’s calculation based on US Current Population Survey (March)

This responds to the logic of skill-biased technological change: technical advances have enhanced the productivity of college graduates, but eliminated the jobs of mid-skilled workers. An estimated 47% of jobs have the potential of being automated, but according to the US White House Council of Economic Advisors, there are big differences between types of jobs: 83% of those earning less than $20 an hour can be automated versus only 4% of those that earn more than $40 an hour.

Higher education can help deflect these shocks. My own research found that during the automation of the 1990s in the United States, those US counties that strongly counterbalanced automation by investing in higher education were able to mitigate job destruction and income losses. It’s interesting to note that this also seems to have enabled them to withstand recent populist trends.

Young people and their families know the importance of college. Around the world, roughly 40% of people under 45 years of age have a college degree, but it is becoming an increasingly expensive endeavor, compounded by a narrowing job market. This will only be exasperated by the pandemic. Take Spain, for example, where roughly 45% of people under 45 years have a college degree. However, in 2018 – well before COVID-19 struck – more than 35% of Spanish graduates were working jobs that didn’t actually require a college degree, and 27% didn’t have a job four years after graduation.

The connection between skills and greater opportunity for people is now well accepted. In Europe, a large part of spending in regards to broadening access to higher education has been shouldered by governments as a subsidy for skills development. These governments have created and expanded new universities and programs while reducing student-staff ratios, aided by demographic trends. But even with these steps taken, the concept still falls short in practice. What can be done?

It is necessary to have a more dynamic relation between the needs of the labor market and what universities are preparing students to meet. In a world where, rightly, education institutions have a high level of autonomy from governments, an easy option might be to enable greater transparency for students and their families about what students will learn during the degree program and for what end purpose. Deciding what college to attend or master’s program to pursue is an important and often difficult decision to make, thanks in part to an abundance of confusing advertising materials and listings of glitzy amenities (such as buildings or dorms) that don’t necessarily differentiate the offerings available for potential students.

Every country should have a sophisticated and government-powered data system that enables students to make better choices at the moment when they are actually making them. To that point, more should be done, again aided by technology, to better advise students on their learning paths.

The US federal government has created the College Scorecard, which allows students to view, for example, the employment and average earnings of recent graduates from their field and institutions of interest, based on reliable, systematic data. No European country has such detailed data available, which is surprising since we have data at our fingertips on everything from stock markets to trending topics. Such tools for academic purposes have no reason to be so elusive in Europe. In fact, the availability of such data would also enable stricter regulation and encourage even more targeted government funding based on outcomes universities achieve and how they create and transfer knowledge.

To paraphrase an old saying, education is hard, but let’s not try ignorance.

A healthy economy and society is one that is able to have a wealth of productive jobs, and is able to fill them with a productive labor force. Some experts have proposed that we abandon the quest for new jobs and, for example, introduce a universal basic income that provides modest salaries for the permanently unemployed who can then dedicate themselves to contemplation or charity work. Yet, this ignores the importance of work to individuals. On average, people derive meaning from their work and tend to identify their place in the world through the lens of their occupation. It is no coincidence that we talk about jobs as “vocations,” Latin for “callings.” In their book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Anne Case and Angus Deaton write about the prevalence of “deaths of despair” afflicting people (particularly men) who have become unemployed or underemployed and see little opportunity due to the automation of their roles or disappearance of the industries that had employed them.

Education remains the key factor for individuals who strive for a better life and for the governments who want to provide that opportunity through inclusive economic and social policies. Improving and revamping education systems with the explicit aim of serving more people to greater effect will be laborious and it will take time. In fact, any changes to the education system made today will take decades to yield tangible results, so there is no time to lose. We must step up to the front of the classroom and get to work.

© IE Insights.