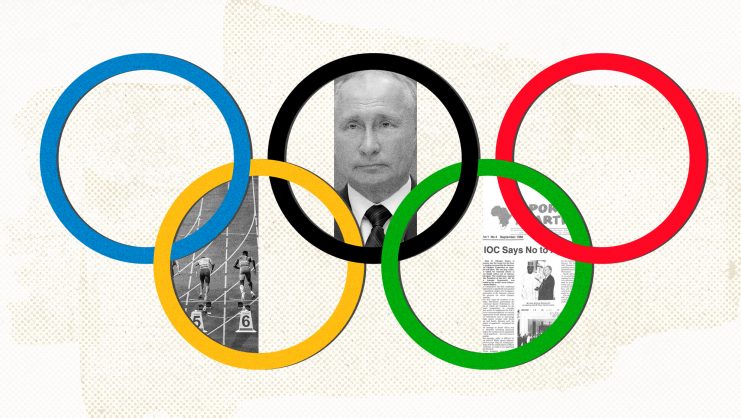

November 17, 2004. In an international friendly at Real Madrid’s hallowed Santiago Bernabeu stadium, England’s black footballers Sean Wright-Phillips and Ashely Cole are subjected to racist abuse from sections of the Spanish crowd. Even through the television coverage, the monkey chants can be heard whenever they touch the ball.

Fast forward 19 years and racist abuse is still making headlines in Spanish football, with Real Madrid’s Brazilian star Vinicius Jr. receiving the same monkey chants. The most recent vile abuse began before Vinicius even stepped on the pitch at Valencia’s Mestalla stadium. It is far from an isolated incident – Valencia’s own Mouctar Diakhaby is one of multiple black players who have complained about the racist abuse they have received while playing in Spain’s La Liga.

Rather than instantly investigating and banning the fans involved in the latest incident, La Liga President Javier Tebas went on the attack against Vinicius on social media, telling the Brazilian to “properly educate himself” on how the league is trying to fight racism. This startling response – and the ensuing backlash – could see Spanish football and the country as a whole, facing a watershed moment in how it deals with racism. While certainly not alone in European football for these problems, Spain’s premier footballing division hits the headlines much more frequently for outwardly racist incidents inside its stadium than its main competitor on the international stage: England’s Premier League. This begs the question: Is Spain as a country simply “more racist” than England, or is this a problem of Spanish football?

Determining how racist a country or society is is an impossible task, made even more difficult by a lack of data on the issue in Spain. The Spanish Interior Ministry ran reports on views of immigration until 2017 and, while not perfect, they give an idea of general views of foreigners in a country where 88% of the population is Spanish-born. Interestingly, while the 2017 survey suggested that 54% of the country has a “positive view on immigration”, intolerance is still prevalent, with 48% saying “they would accept it if there are protests against building a mosque in their neighborhood”. In terms of these intolerances turning into hate crimes, Spain’s numbers are remarkably low compared with the UK’s. In 2021, just 639 hate crimes motivated by race or xenophobia were reported in Spain, compared with 109,843 in the UK from March 2021 to March 2022. The stark difference in the numbers can be partly explained by high underreporting rates in Spain, with 38% of victims not filing complaints according to a 2022 report, and this situation is not helped by the undocumented situation of many migrants in Spain acting as a deterrent to reporting. However, the data suggests that acts of violent, racially-motivated hate crimes are no more prevalent in Spain than in other Western European countries.

More difficult to report through data are attitudes like that shown by Tebas, a tacit acceptance of racism, looking past the essence of someone being targeted because of the color of their skin and grouping it as part of the “cut and thrust” of football. This has been Spain’s issue for 20 years. While the UK has worked to modernize its football, trying to make stadiums more welcoming to all ages, genders, and ethnic backgrounds, Spain has been stuck with the same culture as in the 1990s. Ultras, groups of hardcore supporters – sometimes with strong far-right links – are woven into the culture of Spanish football and remain a feature in stadiums across the country. In contrast, English football has worked consistently to prevent hooligan groups from entering stadiums, and – while far from perfect – the atmosphere in Premier League stadiums is notably less violent for it.

Football is not simply a reflection of society at large but can be a forerunner in bringing about change.

Living in Spain, I have heard the abuse of Vinicius described in terms that seek to play down its racial aspect, along the lines of “he encourages it through provocation”, “all footballers receive abuse from the stands,” or “he’s Real Madrid’s best player, he will always be attacked”. These attitudes are reflected in the response to previous accusations of racism in the country: this is the 10th time La Liga has reported cases involving racist abuse aimed at Vinicius to prosecutors, and it is only after this latest incident that the legal system has acted decisively.

Not only were three arrests made in the Valencia case, a further four arrests were made in Madrid over the hanging of an effigy of the Brazilian star before a match between Real Madrid and local rivals Atletico Madrid in December 2022. Did prosecutors not believe the latter deserved investigation – despite its clear racial undertones – until the PR storm of the last few days? Atletico fans had previously been filmed calling Vinicius a “monkey” but prosecutors dropped the case as the chants lasted “only a few seconds.” As if the length of time racial abuse lasts determines its seriousness.

The Spanish system of relying on prosecutors to pursue cases is slow and ineffective. In the UK, stadium bans can be handed out after a complaint from a local police force, helping to stop racists from entering the stadiums swiftly. The system of stadium bans – of which 1,308 were in force in the UK in June 2022 – does not stop racists from holding their views, but it does prevent racist acts from being given visibility and credence in front of millions of viewers. Racism in British football now occurs for the most part online – seen by the abuse of a trio of England’s black players after their defeat in the Euro 2020 final – and legislation has followed it into the digital sphere. People found to have abused footballers online for their race, sexuality, or religion are now being banned from all stadiums in the country. La Liga must work in a similar way with its clubs, the police, and prosecutors to ensure racist abuse in stadiums is swiftly and severely dealt with.

Spain needs to understand that football is not simply a reflection of society at large but can be a forerunner in bringing about change. Inaction in football tells the country that racist views are acceptable in public discourse, and this message is not only domestic. La Liga is a leading product that showcases Spain to the world, and it cannot allow the scenes witnessed in its stadiums to give a portrayal of an overtly racist country. By taking strong action against racist abuse, Spain can strengthen the process of educating certain sections of society that all actions of racism – such as racist jokes and racist language – maintain a status quo that sees all ethnic minorities stopped more by police than ethnic Spaniards and non-Spaniards struggle to find landlords willing to have them as tenants. Phrases such as “work like a black man” (work hard) or “Chinese work” (monotonous tasks such as data input) are still used in Spanish offices. A reckoning which takes in all aspects of racism – from the abuse of one of the country’s most prominent athletes to outdated expressions – is long overdue.

The recent arrests and uproar surrounding racism in the league need to represent a new era of Spanish football, one where racism, misogyny, and homophobia are condemned to the past, and the skills of its players are left to shine.

© IE Insights.