Climate change, the product of rapid development since the Industrial Revolution, has triggered a global shift from unbridled growth to more sustainable and conscious development. This shift has challenged the traditional mindset that prioritized profit without considering long-term consequences or implications. Today, climate change has evolved into a multifaceted global crisis – political, social, and economic – impacting every region and continuing to drive disparities. It is one of the very few phenomena that have galvanized global consensus and action.

The concept of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) emerged during the 1972 Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, steered by the UN General Assembly. This has thus set a certain tone for the climate change regime: the economies that benefited most from the Industrial Revolution are also those that have inflicted the most harm to the environment.

This carries a weighty responsibility for developed countries because they would account for 79% of historical carbon emissions while representing only 17% (1.3 billion) of the world’s population. The technological advancements, food security, and economic growth that developed countries enjoyed over the past century occurred while developing countries were struggling for independence. As developed countries expanded their markets and refined their economic mechanisms, developing countries were left behind. It is this disparity that forms the basis for the principle of historical responsibility springs forth, justifying the attribution of different duties and obligations to various groups of countries.

The 1992 Earth Summit in Rio produced the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), acknowledging the importance of stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations, established a global and cooperative framework by dividing the 193 UN member countries into three categories:

- Annex 1 countries: Primarily OECD members and economies in transition. These nations have obligations to mitigate and reduce emissions, as they are primarily responsible for the greenhouse gasses already emitted at the time of the treaty’s creation.

- Annex 2 countries: A subset of Annex 1 countries, these “richest of the rich” countries have additional responsibilities. They are required to transfer funds and technology to underdeveloped countries, which are the most vulnerable within this regime. Their greater capabilities and resources position them to foster meaningful change.

- Non-Annex 1 countries: Developing nations without obligations to cut emissions or transfer funds, these countries are given exemptions to prevent the hindering of their ability to develop and catch up economically. The reassigning acknowledges that imposing such obligations would impede their growth and ability to compete with economies that have historically fuelled the climate crisis.

Notably, developing countries are often the ones to suffer the most from the effects of climate change, which threatens to further stagnate their economies. This dynamic underscores the importance of balancing historical responsibility, current capability, and future development needs when addressing the global climate crisis.

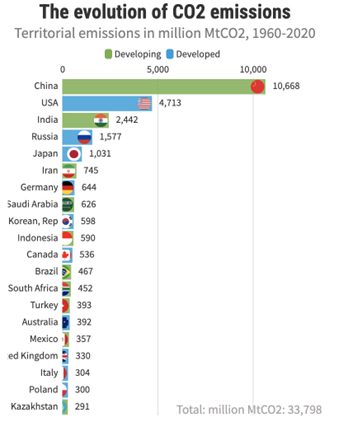

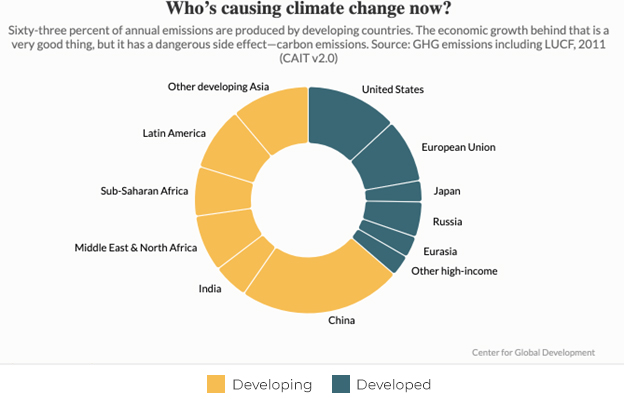

Overall, the political climate regime has been lenient towards struggling economies, ensuring their needs and concerns are adequately expressed. However, the world’s economic situation has changed since the adoption of the annexes in 1992, particularly in terms of CO2 emissions. The difference between greenhouse gas emissions from developing and developed countries has been narrowing. Developing countries now account for 63% of current carbon emissions. This shift is primarily powered by high industrialization and economic growth, particularly in regions such as Asia and Latin America.

Rapid industrial development accelerates the process, as countries experiencing fast growth develop substantial energy demands. In such countries, industrial operations rely heavily on fossil fuels not only for electricity production but also for transport and other industrial-related activities. Urbanization and the growing middle class further amplify emission levels due to increased consumption of goods and services. This transformation is reflected in the global economic indicators: global GDP per capita has nearly tripled since 1960, and CO2 emissions have quadrupled during the same period.

Date: 2015

Date: 2015

Source: Center for Global Development

The colossal environmental cost that has come with development is especially relevant when analyzing the case of China, which is now among the three top global emitters alongside the US and India. These three countries alone comprise 50% of global emissions today.

Date: 2020

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

This is particularly alarming for Annex 1 countries, since two of the three top emitters are classified as Non-Annex 1 countries bearing few obligations under the current climate regime. Among the top emitters, Brazil, South Africa, and Iran can also be observed – all members of BRICS – have emerged as leading players in today’s global economic environment.

This evolution has inevitably triggered a contentious debate: Is it time for developing countries to shoulder more responsibility? Has the CBDR concept yet become outdated for today’s social and economic climate? These questions were strongly discussed during the 2009 Copenhagen Summit (COP15). In negotiations, developed countries pushed for developing countries to take on more significant commitments, even threatening to reduce their own efforts if their demands were not met. Developing countries, in turn, claimed that their developed counterparts were attempting to stifle their growth, labeling it a form of ‘neo-colonialism’. The debate prevails to this day as developed countries’ emissions lower gradually from year to year, while those from developing countries continue to rise – leading to growing impatience and a sense of exploitation among developed nations.

A per capita perspective is imperative to further analyze the complexity of the matter. Despite being responsible for the majority of total emissions, developing countries’ per capita emissions remain well below those of developed countries. Developed nations, along with some high-income oil-producing developing countries, have the highest emissions per capita, with almost all exceeding the global average. For instance, the average person in the US emits more than twice as much as someone living in China, five times more than one in Mexico, and eight times more than one in India.

This disparity underscores the need for a two-pronged approach. Developed nations must speed up the per capita emission cuts while providing indispensable technological and financial help to developing nations to move to sustainable low-carbon growth paths.

Developing countries are, in fact, facing an energy dilemma: their development does require some level of reliance on fossil fuels. Prematurely pressuring these countries to achieve zero carbon emissions dolefully risks stopping new investments in fossil fuels. Such a limitation would paradoxically hamper the scaling of renewables mainly because fossil fuels are often needed to address intermittency issues and meet peak electricity demands, particularly during evenings. Sensitivity, therefore, needs to be accorded to this transition into cleaner energy sources alongside the legitimate energy needs of developing countries. In the meantime, a global approach to reducing emissions must consider the specific conditions of individual countries and their distinct levels of development.

The changing landscape of global emissions calls for a more adaptive framework of international partnership and responsibility. This shift poses a fundamental contested debate: Should developing countries begin to take on more of the burden in our global response to climate change? It is an acknowledgment, therefore, of CBDR recognized in historical emissions, rapid development, and increasing emissions from emerging economies, calling for a reappraisal of responsibilities.

Developed countries, given their historical responsibilities, must lead by example and implement substantial emissions cuts. Simultaneously, they must assist developing countries in managing their own emissions. This support is vital for enabling sustainable growth paths that avoid the pitfalls of fossil fuel dependency. The focus should be on crafting an equitable, balanced, and effective approach that considers both the capabilities and the historical contexts of nations, fostering a shared commitment to a sustainable future.

The conversation must continue, with flexibility, innovation, and shared responsibility at its core. This approach will allow all countries to put forward their fair contribution to the global effort against climate change. By maintaining an open dialogue in this process, it is possible to work together toward a more inclusive climate regime that addresses both historical inequities and present-day realities.

© IE Insights.