It has been six months since Russia’s “special operation” began in Ukraine and the future looks even more uncertain than it did then on February 24. Russia’s invasion and the inevitable war that resulted did not start on that date, however, but had already begun in 2014 when Russia took the Crimean peninsula. Back then, and for the last eight whole years, nobody seemed to be watching or caring much. Yes, a few feathers ruffled at international fora, a few sanctions were introduced but mostly ignored, there was much appeasement and many good words, but nothing serious: no stopping of gas and oil imports, no hardline economic measures, no alternative energy plans, nothing of true substance. This winter, it will be particularly difficult for central and eastern European countries (including the all-powerful Germany) to explain these last eight years of passivity to their citizens.

In 2014, of course, the situation did not seem like it was going to escalate and many firmly believed that, after all, Crimea was quite pro-Russian. So the great idea that Europe came up with was to build yet another gas pipe and continue its energy dependency on Russia (one cannot help but wonder what those eight years could have done for alternative forms of energy). But this time, for the first time, the idea was to bypass Ukraine in case President Putin had further ideas in mind. When Ukraine became an independent state from the USSR on August 24, 1991, neighboring Russia resented, among others, two economic agreements it could not escape from: paying rent for having its Black Sea Fleet anchored in Sevastopol and other parts of Crimea and, second, that during Soviet times all pipelines for gas and oil (but one) were built through Ukraine, meaning that Russia had to pay to transport gas through the independent territory. Putin attempted to solve this latter issue, with European support, by building the Nord Stream I and then the Nord Stream II, the first line of which was inaugurated in 2011 by Chancellor Angela Merkel. Even despite international sanctions after the invasion of Crimea in 2014 (Putin’s attempt to resolve the Black Sea Fleet issue), works to build Nord Stream II continued uninterrupted. With hindsight, it is clear that the idea was not to isolate Russia but to isolate Ukraine in case Putin became picky – and to safeguard the West’s own supply, of course. This is, despite all the rhetoric on nation and freedom on either side, a post-colonial war for the oldest reason in history to go to war, as Rousseau argued in his Social Contract.

Major Russian Gas Pipelines to Europe

Attribution: Samuel Bailey via Wikimedia Commons

Attribution: Samuel Bailey via Wikimedia Commons

The Greeks had a particular type of sin, or crime, known as hubris, for when someone felt they could rise above the gods. Of course, the act of challenging the gods is all fine and good (especially if you are proud enough to do it, like Oedipus), but you should not expect to win. In what looks increasingly like a colossal miscalculation by European leaders (and let us not go into the last few presidents of the US, aside from the incumbent), the idea was that appeasing the leader – literally going around Ukraine with a pipe – could avoid further trouble, particularly for the West.

How long can we appease a man who has given ample proof that he has no respect for human life?

Some European leaders really thought that would do the trick. What goes through their minds now? But of course, what the point in asking? It’s almost like wondering what went through the minds of the infamous “guilty men” (Chamberlain, Baldwin, MacDonald) when Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939. Humans have always thought they know better, can do better, better even than the gods. We have a particularly intellectual blindness that allows us to shut out the signs of something we do not want to see or experience, and regardless of whether it is related to international politics or a partner’s loyalty, we just decide not to see.

Intellectual blindness is directly linked to hubris in that it either “helps” us to willfully persist in a course of action that leads towards destruction (oh, the oft-repeated “but I know s/he loves me”) or it contributes to our taking decisions that are based on miscalculated risks and losses (“s/he is only shy/confused”). In regards to the current war, how many lives and households of ordinary Ukrainians were worth one kW of Russian gas-produced energy used in Central Europe? How many were worth one liter of Russian imported oil? How long can we appease a man who has given ample proof that he has no respect for human life, divergent opinions, people’s dignity, or the rule of law – neither in Russia, nor in Georgia, Syria, Chechenia, or Ukraine? What exactly did European leaders expect when they made business, without a plan B, with such an individual and continued to do so after 2014? Did they actually expect a sudden conversion to liberal democracy, like Saul falling from his horse? Or, perhaps they were hoping for a nice game of chess against the world’s second most powerful army encamped a few kilometers away? There is a fine line between hubris and stupidity, and the coming cold winter nights will provide ample opportunity for those European leaders to give it some thought.

Once the full-fledged war was launched against Ukraine, many hoped that the Russian people would do for us what we did not during the last eight years – and that is bring down President Putin. The rebellion would come from within, with our help of course, and once President Putin was out, the war would be over and we in the West could once again say that we have contributed decisively to the advancement of democracy in Russia. This is where the fine line disappears.

Only a complete ignorance of Russian society and its history could permit such delusion. Does no one read War and Peace any longer? Has everyone forgotten how Kutuzov defeated Napoleon, the greatest military mind of his time? Are we to ignore how Russians have stood behind their leaders in times of war, as almost any citizen rallies in times of crisis around their own nation, regardless of their opinions during peacetime? And what about the many atrocities that were forgiven of Stalin after Stalingrad and Leningrad? When Putin took Crimea in 2014, his popularity rose to 72% in the first week. When he launched war in February 2022, demonstrations in some Russian cities were broadcast by western media – and as if the crowds were an indication of a coming democratic triumph, their numbers were repeated: 800, 1,000, 2,000 in Moscow! Moscow has a population of ten million people. Two thousand is not a significant number. There were ten times more people than that who served as extras in filming The Lord of the Rings. Yes, there are very brave people in Russia who disagree, and outwardly, with Putin’s politics both before and after the invasion of Ukraine, mainly in academia and in intellectual circles. And, of course there are many such people who have had to flee to Armenia, the US, or Poland. But we should not forget that Russia has a population of 143 million people, which means there are not enough who stand against Putin’s politics to make a difference.

So no, the Russian people are not going to solve our moral and energy crisis.

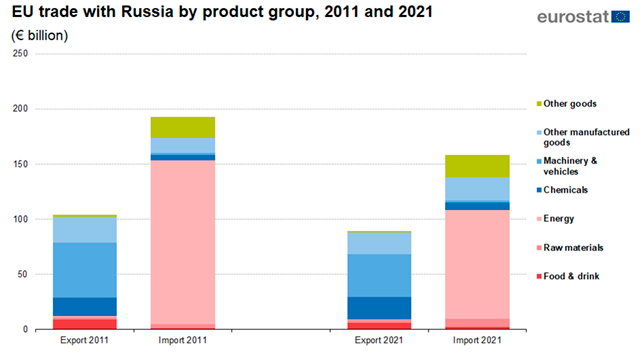

But, anyway, why should the Russian people overthrow Putin when it is we in the West who have an energy and (depending on whom you ask) moral crisis, not them? Many people in their mid-forties and older in Russia remember perfectly well how the situation was in 1999, when Putin first came to power. They were living in a crippled economy, there were mafia landlords doing as they pleased, there was increased insecurity in the streets, collapsed state pensions, a bombarded parliament thanks to Boris Yeltsin. (Ah, Yeltsin, that great friend of the West who destroyed, maybe forever, any power invested in the national parliament or Duma with a fabricated coup d’état that subsequently gave any president of Russia almost absolute powers.) Then there came Putin, who seemed able to eliminate or control the mafia, make the economy grow, and rule effectively if not democratically for the first time in a very long time, and certainly for the first time since the end of the Soviet Union. Finally, ordinary Russians could save enough to travel abroad, buy themselves nice clothes, and cultivate an image that countered how they were portrayed – as pariahs and terrorists – in American films. If there was a fundamental flaw in what Chris Miller has called Putinomics, it was the excessive dependence on exports of fossil fuels. In the years when the Russian economy was blooming, Putin should have but did not diversify his commercial balance. So should have the EU. The trade balance with Russia was always negative for the EU. Traditionally, the EU exported manufactured goods, machinery, vehicles, and chemicals to Russia, as well as food and drink – and the EU imported mainly, by a large difference, energy.

When Putin invaded Crimea, the first international trip he made was to India and China, with whom he signed trade agreements to buy from them what so far he had been buying from the West. He had done his homework. At the same time, he reactivated old national industries to manufacture, for the first time since the Soviet era, Russian washing machines. A new pride in a renewed self-sufficient economic autarchy invaded Russian households (a tone that can also be found, by the way, in the slogans of Brexiteers.) Russians could rally behind their President and be a proud nation again because they did not need the West.

What Putin is a particular master at, undeniably, is in giving back a sense of national pride to the majority of Russian citizens, and it is a pride that is traceable back into Russian history to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. A pride of being Russian that has always endowed the people with a messianic sense of history against the corrupt West and with dreams of an everlasting empire, a sense of history that is present in Dostoyevsky and Solzhenitsyn (apparently one of President Putin’s favorites). As is sung in the Russian national anthem: “You are the only one in the world! You are the only one – the native land so kept by God! So it was, so it is and it will always be so!”

Last July, popular support for Putin was above 80% according to the internationally acknowledged center of public opinion Levada. It was only 69% in January. So no, the Russian people are not going to solve our moral and energy crisis. Putin is their president. If we find it all morally repulsive, we should stop doing business with him. This is clearly what we should have done long ago.

Source: Eurostat

© IE Insights.