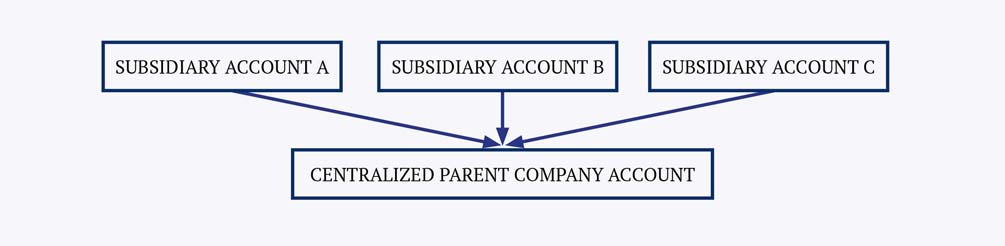

To make good decisions and become highly efficient, businesses need good cash-management tools. One option is cash pooling: the centralization of a group’s bank balances in a single account. In order to consider this option, the organization must have a well-developed IT system, since cash pooling concentrates a vast number of movements and balances into a single account—both in real life and for accounting purposes.

As you might expect, the companies that adopt cash-pooling systems tend to be relatively large. Below a certain size threshold, it makes little sense to adopt such a scheme. In theory, however, cash pooling can be used by all sorts of companies. The considerable advantages of this approach fall into two categories:

- Offsetting balances. Having a single account makes it possible to offset debit balances with credit balances or surplus money. The advantage is obvious: Offsetting one balance with another eliminates the need to pay the interest rate differential between the debit balance and the credit balance, since the debit balance will normally be higher.

- Simplicity and capacity. Centralized management has various advantages: greater organizational capacity, simplified administration, and—thanks to the existence of a single centralized account—a better position in negotiations with financial institutions.

Types of cash pooling

Cash-pooling schemes offer considerable flexibility and can be classified according to various criteria.

The first way to classify cash-pooling systems has to do with how intensely bank balances are transferred from subsidiaries to the parent company. Most systems fall into one of three categories:

- Zero-balance cash pooling. The balances of all subsidiary accounts are swept into the parent company’s main account at the end of each workday. This is the purest form of centralized cash pooling: debit and credit balances offset one another and the group’s cash management is centralized.

- Cash pooling with one-day loans. This approach also involves sweeping the balances of subsidiary accounts into the parent company’s account at the end of the day. A reverse sweep then takes place the following day, reinstating the balances in the subsidiary accounts first thing in the morning. Under this system, the credit and debit balances offset one another but cash management is not centralized, so the subsidiaries have greater autonomy.

- Target-balance cash pooling. This approach starts with either of the two aforementioned schemes but adds a twist: The daily sweep of funds from the subsidiaries to the parent company does not leave the balance of the subsidiary accounts at zero. The target-balance approach is often used in systems without a reverse sweep, since it ensures that subsidiaries do not start the day with empty accounts.

Centralized management has various advantages: greater organizational capacity, simplified administration, and—thanks to the existence of a single centralized account—a better position in negotiations.

The second way to classify cash-pooling systems has to do with how funds are transferred. Three types of schemes can be identified:

- Cash pooling with individual transfers for each movement. A separate transfer takes place for each movement generated by the subsidiary. This approach results in an excessive number of transactions and is overwhelming for the organization and accounting department.

- Cash pooling with bulk transfer of movements with the same value date. This is the most common system, as it is both simple and highly efficient. Movements generated by a subsidiary on the same value date can be grouped together and swept into the parent company’s account. In other words, there are as many transfers are there are groups of movements.

- Single-transfer cash pooling. All movements generated by a subsidiary are transferred at once. The value date for the sum of the movements is the same as that of the transfer. This system normally leads to information loss, since not all of the subsidiary’s movements or transactions will match the value date of the transfer.

Whichever cash-pooling system you choose, it is important to set it up for all of the banks that the group works with.

Cash-pooling can also be classified according to whether or not money actually changes hands:

- Real cash pooling. Money is actually transferred between the subsidiaries and the parent company.

- Notional cash pooling. No money is actually transferred. However, for the purposes of interest charges, the bank adds up the various balances and considers the company’s overall position, rather than looking at each account individually. In some cases, separate interest payments are made to each subsidiary, although the debit interest and credit interest tend to be the same. The bank subsequently makes a combined payment with additional interest in the event that the combined balance is a debit balance.

Whichever cash-pooling system you choose, it is important to set it up for all of the banks that the group works with. Otherwise, things can become very confusing.

Cash pooling is a tool that allows organizations to operate more efficiently. It is important to remember just how vitally important and influential cash management is for many business decisions, particularly in relation to investments and expansion. Nowadays, the funds-flow statement, the statement of source and application of funds, and the cash-flow statement are vitally important for any business. Cash management is a key tool that large companies should leverage and optimize—and cash pooling is a good place to start.

© IE Insights.