Developing a strong personal brand is essential for every professional who wants to stay relevant — whether she or he is looking for work or new projects, aiming for a promotion, or leading a team towards a goal. When a professional’s intentions and values are consistent, and what they can bring to the table is clear, their influence amongst peers and colleagues grows, projects are accomplished, and leadership takes shape. The ever evolving process of building one’s personal brand is particularly important for those working in the gig economy (a direction in which we are all more or less headed) and during times of instability (for example, the current environment.)

However, a personal brand is not one size fits all and the process of developing one can pose specific challenges for women. It is unnecessary to detail the ways in which women with strong personal brands – like Hillary Clinton and Oprah Winfrey and Margaret Thatcher – have been labeled as aggressive, opportunistic, and bossy. Being clear, strong minded, and decisive is imperative to success for a leader, but for those who also happen to be female, there is another success factor, which can be somewhat counterproductive, and that is likeability (aka the L-Factor.)

As Sheryl Sandberg described in her widely read, if not widely accepted book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, the higher a woman climbs the ladder – whether it be professional or political – the more difficulty she tends to have with the L-Factor. Basically, she begins to start leaking popularity. It is the opposite for men. Sandberg writes, “Success and likeability are positively correlated for men and negatively for women. When a man is successful, he is liked by both men and women. When a woman is successful, people of both genders like her less.”

Unconscious gender bias has been around for a while. In “Howard vs Heidi,” MBA students were given a case study of an actual entrepreneur who happened to be both successful and a woman. Half of the students were told the entrepreneur’s name was Heidi Roizen (the entrepreneur’s actual name), and the other half were provided with the fictional name Howard. When asked to rate the protagonist of the case study, the students rated Heidi and Howard equally competent, but found Heidi selfish and not the type of person you’d want to work for or hire.

Gender expectations indicate that women should be warm, protective, and agreeable – and self-promotion does not align with these gender expectations. When a man self-promotes, he is usually considered confident, strong, or reliable.

To get around this dilemma of bias and gender expectation, women leaders must endeavor to let go of the need to be liked when leading people. This is not easy for a variety of reasons and the desire to be liked is obviously complicated, but regardless of where the need comes from, a strong personal brand can help women stay focused on their long term goals. This is because, in order to create a strong personal brand, one must do the hard work of clearly defining one’s personal goals and values, and align them. This authenticity of self enables leaders – both women and men – to keep their objective front and center and makes decisions that might sometimes be unpopular. The armor of a personal brand is particularly helpful to women because female leaders tend to spend more time fighting that short-term focused and whimsical L-Factor.

More than a decade ago, Paul Arden wrote in his book Whatever You Think, Think the Opposite the story of “Steady Eddie” and “Reckless Erica.” “Steady Eddie” represented the risk-averse corporate employee who rises quickly in his youth because he is nice and obedient. But when the time comes to hire a Managing Director, Eddie is discarded because, while he is a good employee, he does not innovate and does not have a public profile. At fifty years of age, he is fired. He didn’t make it to the top of his career ladder even though, technically, he didn’t do anything wrong. Of course, that’s exactly the problem, he didn’t really do anything. Steady Eddie did not take enough risks.

On the other side of the character spectrum, “Reckless Erica” is a creative professional who recently started working in an agency. She’s sometimes irritating but is also enthusiastic and good at generating ideas – many ideas that are indeed impossible to implement, but there are some that do work and get the justified attention of her colleagues. Erica is eventually fired, but has no trouble finding a new job because many people remember the good idea (amongst all the others) that she generated during her tenure at her previous employer. The cycle repeats several times and by 40 she is a well-known and respected professional in her industry. Why? Because she had the guts to be different and she took enough risks that some good ideas stuck.

This story illustrates the difference between “respect” and “love.” Everyone loved Eddie, but it didn’t help him create a sustainable position. Not everyone loved Erica, but everyone respected her. While respect is more difficult to earn and involves taking more risks, it is a stable and stronger platform on which to build a personal brand.

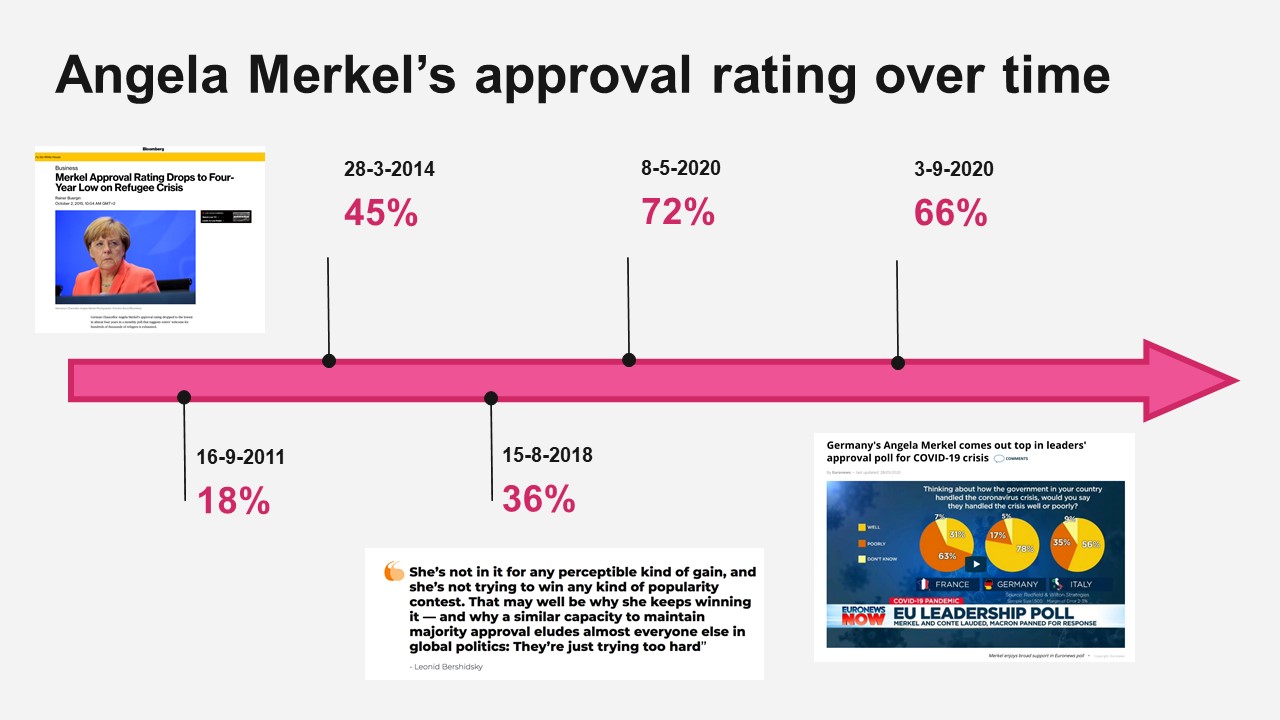

Another example of a leader (who is also a woman) with a personal brand built on respect is that of Chancellor Angela Merkel. Her public approval has varied markedly with different decisions made in the exercise of their functions. Yet Merkel, regardless of the polls, has remained true to her vision of a united and inclusive Europe, losing approval points with many decisions she made to implement this vision. She chose to stick with what she believed in over momentary popularity, and this earned her respect, and thus wielded her more influence in the long run. There are no shortcuts in this regard.

Figure 1. Angela Merkel’s public approval over time

Source: Developed by author

The British economist John Kay believes that our goals are best achieved indirectly because, at least usually, the current environment is uncertain and the effects of our actions depend on the reactions of others and objectives are multi-dimensional. It is essential to consider this concept when building a personal brand because it helps us understand, as Merkel does, that if we want to be respected in the long run, we must also accept the short term loss of popularity points. The road to respect is longer, but as Margaret Thatcher – another strong but not particularly liked leader – used to say: “If you set out to be popular, you will be willing to compromise on anything at any time and you will achieve nothing.”

Being a leader is a complicated and constantly changing endeavor – and that holds true for the manager of a project team, the head of a department, a c-level executive, and the leader of a nation. It is difficult and important work to manage likeability and respect, short-term objectives and long-term goals. The key is deciding where to place relevance at the appropriate time. When focusing on likeability in the short term, leaders find themselves caught up in a popularity contest. But when the L-Factor is a long-term leadership quality, it translates into respect because employees or supporters trust the leader to make decisions for the good of everyone, not just themselves. For women developing a strong personal brand, it’s important to not get mired by the desire to be liked at every turn, but to focus on long-term likability because this is what makes sustained and impactful leadership possible.

© IE Insights.