What does a book published by a Chinese academic in 1991, America against America, which went largely unnoticed at the time, have to do with one of the most singular events in US history, the January 6, 2021 assault on the Capitol? The would-be uprising in Washington awakened in China an unusual interest in the aforementioned book, reaching a price on the Kungfuzi online antiques marketplace of more than $2,500, some 3,000 times more than what it cost three decades ago.

When Wáng Hùníng (王沪宁) wrote the book, China was exploring new freedoms under Dèng Xiǎopíng (邓小平) and not even the most astute China watcher expected the dragon to become what it is today (although Napoleon did comment in 1816 that it was better to let China sleep, because it would shake the world when it awoke.) The same could arguably be said of Wáng Hùníng.

America against America is fascinating for several reasons. The first is that, like a modern Tocqueville, Wáng Hùníng saw in the American phenomenon a model that would allow him to explain why the Chinese phenomenon fell behind the developed nations. And here we are: sometimes it seems as though time stands still, and we relive an event that took place many decades before. In 1923, Spanish writer Vicente Blasco Ibáñez wrote in La Vuelta al mundo de un novelista (A Journalist’s Trip Around the World) that in the Chinese city of Shěnyáng (沈阳), “near the station there are modern buildings of many floors, which imitate American architecture with all its audacity.”

It could be argued that, since the demise of the Great Helmsman, the Dragon has audaciously imitated many of the practices that have made America great. It is safe to say that no matter how many Chinese characteristics have been applied to the dragon model of development and growth, the advances achieved, especially in science and technology, have been based on American ideas. It is only since the second decade of this century that the dragon has begun mastering its own fire.

Another interesting aspect of the book is the youthful sense of wonder the author– who is considered the éminence grise of current Chinese politics – has towards the United States at that time in the early 1990s, particularly with the 4Cs. The American eagle was awash with what the Chinese dragon lacked: cars, phones (call is the word he uses), computers, and credit cards.

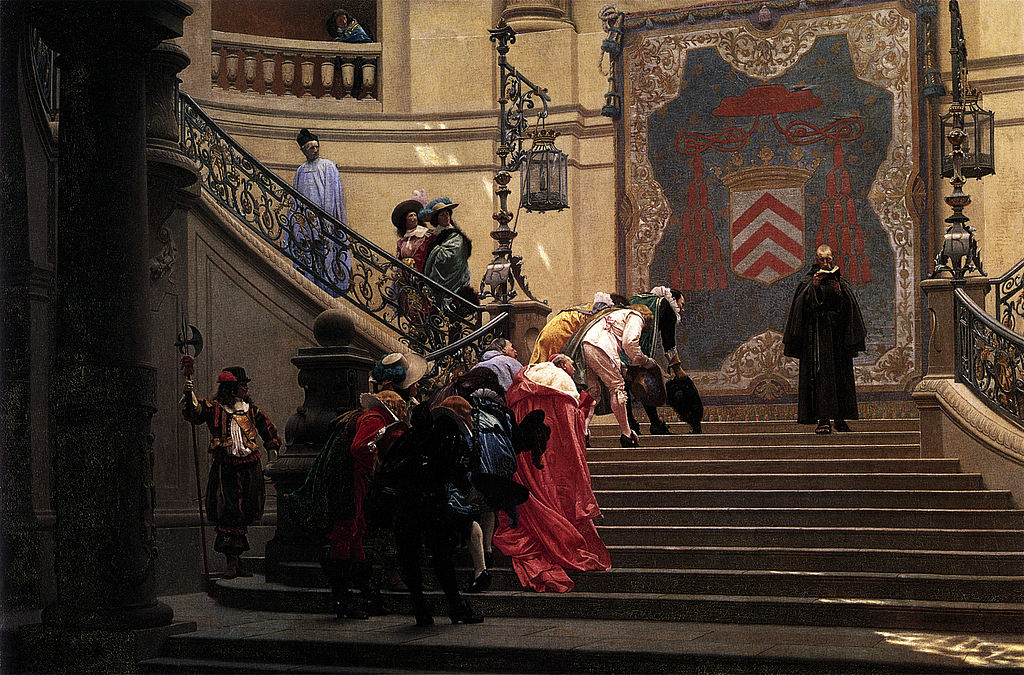

L’Éminence Grise, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicting François Leclerc du Tremblay, better known as Father Joseph, secretary to Cardinal Richelieu, and considered the power behind the throne, descending the grand staircase of the Palais Cardinal.

These 4Cs are now, of course, everyday items in China, where there are more vehicles (300 million) than most countries have people. Unsurprisingly, the Dragon tops the list of countries with the largest number of phones in the world, 1.382 billion, compared to 317 million in the United States. China is also far ahead in the use of credit cards, because all transactions are done not just by credit card, but by way of the WeChat application known in Chinese as Wēixìn (微信).

And of course China is well populated by computers. Filippo Santelli, a former correspondent of Italian daily La Repubblica points out in his new book La Cina non è una sola (which translates roughly as There’s more than one China), that the telephone (not the computer) is the means by which the Dragon has entered the Internet age and become digitalized. Santelli notes a survey conducted by Beijing University in which 99.8% of respondents said the medium they used most to read news is their smartphone. This trend is global – Santelli argues – even if China’s example is extreme.

What’s also extreme is how, when deciding on an object of study, scholars tend to take the precaution of pointing out that the object – China, America, or whatever else – is not monolithic, not homogeneous, not easy to understand. Wáng Hùníng has commented that by calling his book America against America, his aim is to show that the United States is not a simple homogeneous whole easily explained in a single sentence. Santelli alludes to the same thing with the title of his book. Yet, it should seem obvious that the United States is a mass of innumerable contradictions. As is China. Is it always necessary to affirm this, to highlight the intricacy of the matter? Or is it more likely that we are not in a position to assume the complexity of the reality we face, and it is apparently always necessary to remind ourselves and others of it? By definition, shedding light on something means the topic is obscure and acknowledges that everything has its nuances and its twists and turns.

So, what about this author, Wáng Hùníng, and his book thrown into the spotlight after last year’s assault on the Capitol? To begin with, it must be noted that even though he was signed on by former President Jiāng Zémín (江泽民), Wáng Hùníng not only survived to serve under Hú Jǐntāo, which is unusual enough, but on top of that, he remains active with Xí Jìnpíng, whom he accompanies on all state trips. Wáng Hùnínge is also one of the seven members of the exclusive Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CCP. And all this without ever having been appointed to run a region or a city or a ministry.

In Chinese political circles, Wáng Hùníng is compared to major historical figures such as the sociologist and philosopher Hú Qiáomù (胡乔木), considered the power behind Máo. In the West, he is often likened to François Leclerc du Tremblay, better known as Father Joseph, Cardinal Richelieu’s courtly adviser. In any event, most agree that he is the éminence grise of Chinese politics – so much so, in fact, that he is also referred to with the censored name of dìshī (帝师), the emperor’s teacher. The name is irreverent because it suggests that the president of China is both an emperor and a student. Both suggestions threaten the foundations of political correctness in China.

Realists could not live without elevating the spirit, nor dreamers without descending to earth every now and then.

Even though he has authored more than 20 books and has been empowered with unparalleled political experience, it is still not clear whether Wáng Hùníng is a realist or an idealist. Realists tend to limit their dreams, keeping their feet on the ground, while idealists (dreamers, utopians, whatever term you prefer) tend to give free rein to their dreams. The tension between the two prototypes is evident in all areas of life, but the difference between them is not as clear as it might seem at first glance.

In practice, people who call themselves realists never stop dreaming, and those who call themselves dreamers are often prepared to be highly pragmatic when it comes to fulfilling their ideals. Moreover, in everything that both do, the distance from reality, and the descent, or approach to it, are powerful metaphors for whatever they intend to do. Realists could not live without elevating the spirit, nor dreamers without descending to earth every now and then.

In which category would you place a man who is extremely influential in political terms but describes himself as a reader rather than a teacher, who has retained his position at the top because he keeps his head down while holding on to his ideas and, in fact, does everything possible to spread them, as he has with the Chinese dream? How to define a man who has managed to shape the reality of not just China, but the world? According to Timothy Cheek, author of The Intellectual in Modern Chinese History, Wáng Hùníng is one of the top thinkers in China’s modern Establishment. Wáng Hùníng may indeed be a category to himself, just as the storming of the Capitol may also have created an as-yet unclassified historical category. Perhaps the most fascinating book is yet to be written.

© IE Insights.