Some weeks ago, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen advocated for a global minimum corporate tax, arguing that the U.S. is committed to end “the race to the bottom” on corporate tax rates and prevent multinational firms from shifting investment, jobs, and profits overseas. However, before delving into the global minimum tax and how it would actually work, it is important to first clarify how firms are taxed when they do business in more than one country. In an era of increasingly global markets, it is not at all uncommon for firms to earn income in multiple countries and sometimes they earn more income outside their home country than inside it. By investing abroad or engaging in business abroad, they also become subject to the tax laws of at least two countries: the home country where the firm resides and the host country where the foreign income is earned.

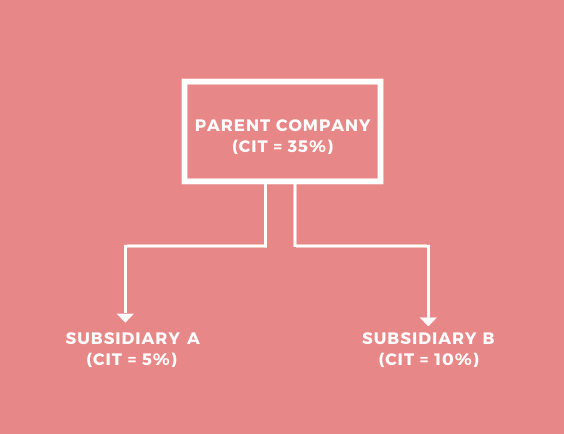

As it is currently structured, the international tax system allocates taxing rights to either the home country, the host country, or both countries. While the host country taxes only income that is earned within its borders, the home country can choose whether to “top up” the foreign tax with its own tax or exempt the foreign income from further taxation, depending on whether the home country applies a worldwide or a territorial tax system. For example, let us assume that a multinational firm operates in two foreign countries, A and B, in addition to the home country. Suppose also that the home country taxes the firm’s profits on a worldwide basis and relies on foreign tax credits to alleviate double taxation of foreign income. Further, assume that the host countries A and B tax the income earned within their borders at rates of 5% and 10%, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – A multinational firm operating in multiple jurisdictions.

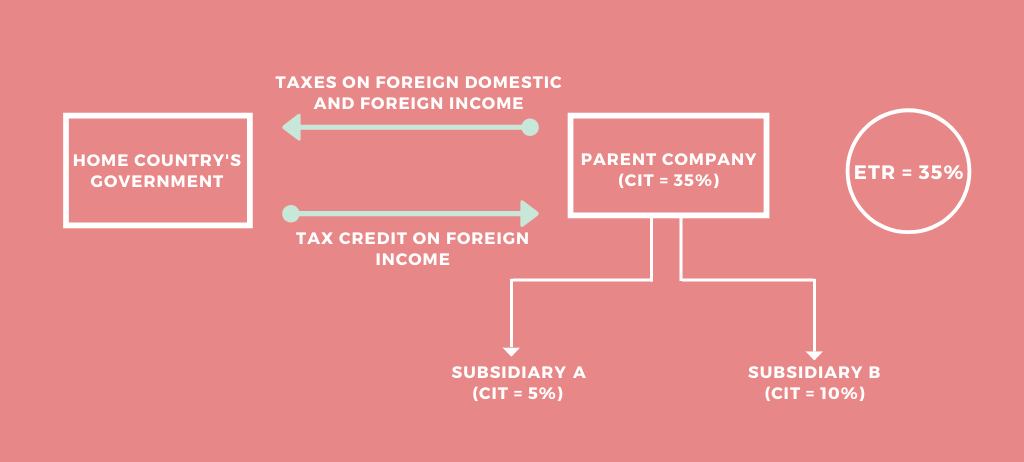

For each foreign subsidiary, the multinational firm first pays a corporate income tax on its foreign income earned in the host country. Once the subsidiary distributes the amount of foreign income to its parent company, the home country then taxes the grossed-up foreign income on a worldwide basis annually and provides the multinational firm with a foreign tax credit up to the amount of taxes paid in A and B. As a result, the multinational firm pays the same 35% corporate income tax rate on the domestic as well as foreign income regardless of where the foreign subsidiaries are located. This mechanism allows the host countries to set competitive tax rates below the home country’s tax rate – without deterring inward foreign direct investment or discouraging domestic investment and employment – and the home country to tax the worldwide income of its resident firms at its current tax rate. Hence, the overall effective tax rate (ETR) of the firm would be equal to 35% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – A multinational firm operating in multiple jurisdictions subject to a worldwide tax system in the home country.

However, note that if the home country defers taxing the multinational firm until the foreign income is repatriated, the overall tax burden would be much lower. For example, the US tax code exempts foreign profits that are deemed “permanently reinvested abroad”. Because of this rule, many US multinationals have accumulated more than $2.6 trillion of profits in foreign subsidiaries and have been able to significantly reduce their overall tax burden as if they operated in a territorial tax system.

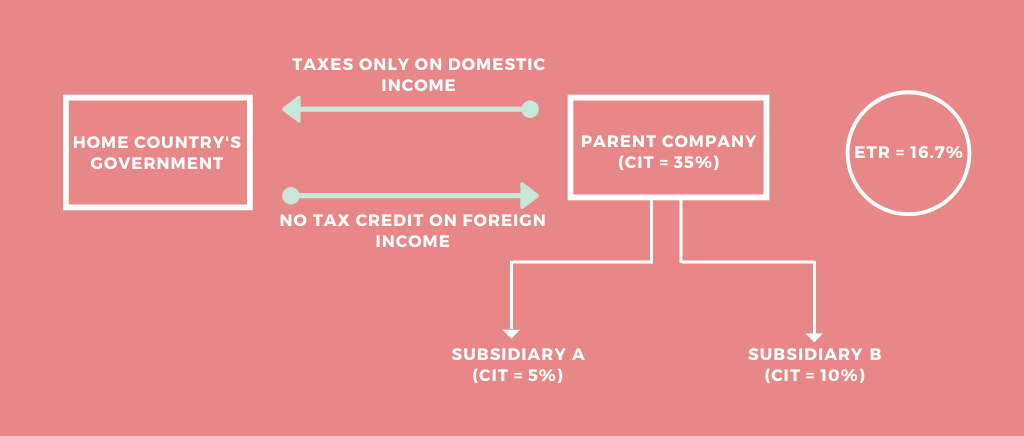

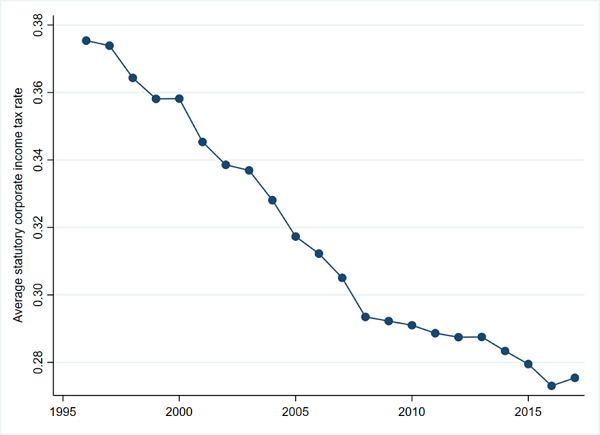

Under a territorial tax system, the home country does not tax the foreign income and does not provide a tax credit for foreign taxes paid. Returning to our previous example, the multinational firm operating in host countries A and B would now be subject to very different corporate income tax rates across the jurisdictions in which it operates. Moreover, the home country’s additional tax on the foreign income and the tax credit for foreign taxes would be both equal to zero and the overall ETR would be equal to 16.67% (see Figure 3). Clearly, the territorial tax system creates incentives for host countries to lower their statutory tax rate as much as possible in the attempt to attract foreign investment within their jurisdictions and spur economic growth. However, over time, the result of this wicked mechanism has been a “tax competition” or “race to the bottom” among countries (see Figure 4) that has led multinational firms to relocate assets (investment), jobs (employment), and even profits, where they would find the lowest level of taxation and the sweetest tax deals (see, for example, the case of LuxLeaks).

Figure 3 – A multinational firm operating in multiple jurisdictions subject to a territorial tax system in the home country.

Figure 4 – Average statutory corporate income tax rate of major OECD countries.

To cope with the “harmful tax competition” that undermines countries’ ability to raise taxes, in 2013 the OECD launched the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. This project aimed at preventing multinational firms from shifting profits from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions, which could, according to the OECD, cost countries as much as USD 240 billion annually, that is, the equivalent of 10% of the global corporate income tax revenue.

Since the launch of the BEPS project, some progress has been made and countries have been able to partly cope with multinationals’ profit shifting activity. Nevertheless, the OECD considers that tax avoidance and profit shifting still represents a key concern for countries to such an extent that, in November 2019, the OECD launched a new project called Global Anti-Base Erosion Proposal (GloBE), whose intent, among other things, is to reach an agreement over a global minimum tax on corporate profits.

Let us now analyze how such a global minimum tax would work within the framework outlined above, with the assumption that the global minimum tax would be set at 21%, similar to what President Joe Biden has proposed. Recall that countries A and B have statutory corporate income tax rates below that of the home country. Hence, under a global minimum tax regime, they would face an additional levy by the home country. Specifically, country A would face an additional levy of 16% and country B, 11%. Crucially, though, what happens to the multinational firm’s total tax burden depends on whether the home country applies the worldwide or territorial tax system. Under a worldwide tax system, the home country would continue to tax the worldwide income at 35% and provide the multinational firm with a foreign tax credit for the taxes paid abroad. Hence, the multinational firm’s ETR would continue to be 35%. However, since the host countries A and B would now face an additional levy of 16% and 11%, respectively, they could increase their level of taxation up to the floor set by the global minimum tax (21%) without fear of deterring inward foreign investment and potentially put a halt to the “race to the bottom” war.

The situation changes if the home country follows the territorial tax system and does not tax foreign income nor provide a tax credit for foreign taxes paid. In such a case, the top-ups to the global minimum tax in host countries A and B are the only additional taxes due in the home country. The gap in corporate income tax rates between the home country and the host countries has been reduced to 14% but not eliminated. In such a scenario, the firm’s ETR would be equal to 25.67%, which is significantly higher than the ETR under a pure territorial tax system with no global minimum tax.

Will the global minimum tax solve the problem of tax avoidance and profit shifting? First, as long as there are countries where multinationals’ profits are subject to very low levels of taxation (e.g., tax havens), there will always be incentives for multinational firms to engage in profit shifting. As we have seen earlier, the global minimum tax alleviates the issue of low taxation but does not solve it entirely, especially nowadays that most countries around the world follow the territorial tax system (or a hybrid model closer to a territorial system, such as that of the United States after the 2017 TCJA). Perhaps, the first best solution would be, for the home countries to move back to worldwide tax systems rather than adopt a global minimum tax. Second, the desire of smaller and developing countries to attract foreign investment has generated a harmful tax competition in which countries compete fiercely for multinationals’ assets, jobs, and profits not only by lowering the tax rate, but also by offering generous targeted (firm-specific) business tax subsidies. However, these tax breaks could seemingly reduce a firm’s tax burden regardless of the level of the corporate tax rate. Hence, even if the headline tax rates increase up to a global minimum level, it is still possible that countries will continue to compete with each other using different tax tools.

Thus, in light of these evolving scenarios, it remains to be seen whether the member countries in the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS will reach an agreement on the global minimum tax (expected for mid-2021) and whether such an agreement will truly end tax competition among countries as well as tax avoidance and profit shifting by multinational firms.

© IE Insights.