Political turnover is a cornerstone of democracy. For one, the possibility of being voted out of office pushes politicians to perform better – delivering public services and avoiding corruption. Knowing that they will have another chance to get back to power helps a government that loses accept the results and go to the opposition. And the occurrence of political turnover itself often brings positive effects, including gains in economic and human development.

But before new leaders gain office, electoral accountability can create significant disruptions. My research has revealed that the outgoing politicians (so-called “lame ducks”) disrupt government and can hurt service delivery in the period between their electoral defeat and their successor taking office. This happens because they have distinct constraints, incentives, and motivations, which they pursue strategically in their final weeks in office.

There is, in fact, a critical moment of democratic governance that can unsettle public administration and services. Discussions about elections usually focus on three key moments: campaigns, election results, and the policy changes of the new administration. But one crucial phase is often overlooked – the lame-duck period. Outgoing governments are neither powerless (as the image of the “lame duck” would have us believe) nor short-lived. Many countries experience long transition periods, often lasting several months.

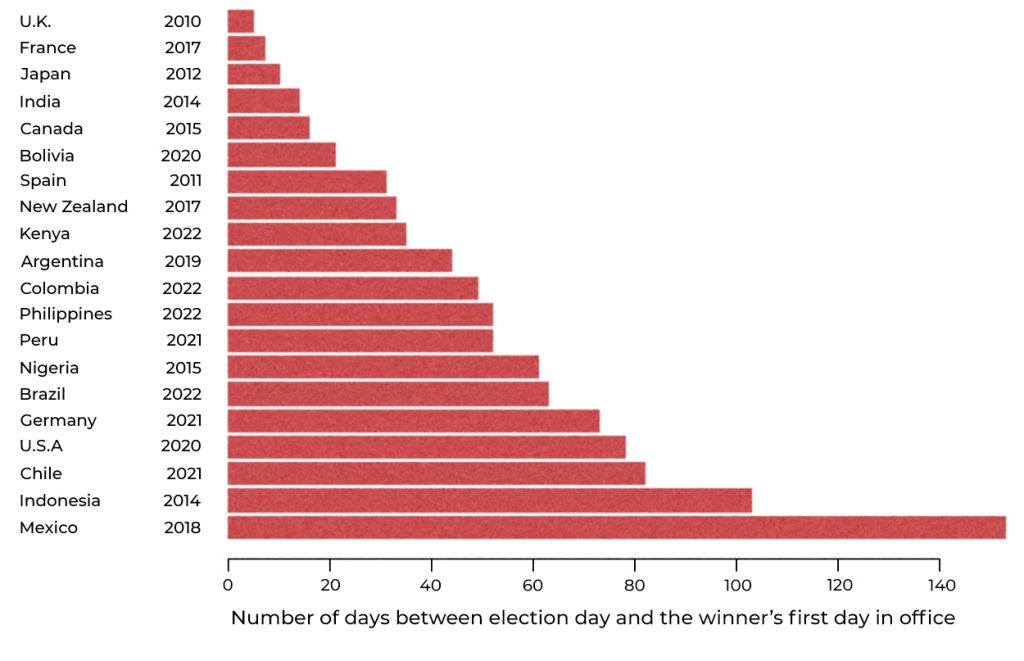

Figure 1. Recent transition periods in a sample of 20 countries. Data corresponds to the latest instance, until January 1, 2023, when a new party reached national-level executive office through an election.

What is special about lame-duck politicians?

Lame-duck politicians differ from regular incumbents in three key ways. First, unlike during the campaign, lame ducks face no uncertainty about their political fate. Unless they resort to authoritarian tactics, lame ducks know their exit from office is imminent. With public and media attention shifting to the winners, lame ducks focus on their own interests, often at the expense of good governance, the smooth functioning of government, and citizen wellbeing.

Second, lame-duck politicians are concerned with laying the groundwork for their (or their party’s) return to power. Politicians who lose a re-election bid often run again in the future. In Brazil, about half of the mayors who narrowly lost a reelection campaign ran again in the next election. Even when ousted leaders do not run again, their party typically will. During their remaining time in office, lame ducks therefore have an incentive to use executive authority to make that return more likely.

Beyond political incentives, lame-duck politicians often worry about personal risks – especially prosecution. In many systems, incumbents have some degree of immunity or protection from prosecution, which they lose after leaving office. Additionally, once out of office, politicians have fewer resources to exert formal and informal pressures on accountability actors. Recent studies on India and Brazil show that incumbents are less likely to be convicted than politicians who lose their reelection, despite formal protections for judges in both countries. The number of national heads of government convicted for corruption after leaving office has steadily increased since the 1980s, and it may be even more common for subnational authorities. To avoid prosecution, lame-duck politicians can use their final months to cover their tracks or to reduce signs of wrongdoing in their administration.

Why can lame-duck politics be bad for democracy?

After losing a reelection campaign, lame-duck politicians use their final weeks in office to pursue two main goals: laying the groundwork for a return to power, and shielding themselves as much as possible from prosecution. To achieve these goals, lame ducks can strategically use their authority over procurement, regulations, and bureaucratic appointments, among other tools of government.

Be it through purchases, regulations, or hiring and firing, lame-duck politicians can use executive authority during their remaining time in office to limit the next administration’s ability to govern. For instance, they can tie their opponents’ hands with contracts, regulations, or personnel they would otherwise not desire. They can also make changes in spending or personnel to improve compliance or to obscure past mismanagement, reducing the risk of future prosecution.

Along the way, public services are likely to suffer. There are four reasons government agencies can become less functional during a lame-duck period. First, the accumulation of changes, ambiguity, and uncertainty, combined with bureaucrats’ expectations for a renewed leadership, can stall government activity. Put simply, things (including critical things like healthcare services) may be postponed. Second, during the lame-duck period, there are likely to be disruptions in the procurement of goods and services on which bureaucrats depend to do their job. Third, the hiring and firing of personnel makes it harder for agencies to deliver public services, both directly (e.g. through the exit of experienced bureaucrats) and indirectly (through the disruption to teams and organizations). Finally, senior officials are less likely to be able and willing to put pressure on the bureaucracy to deliver. All in all, the transition period between an incumbent’s electoral defeat and the beginning of a new administration can become a time of reduced government activity and accountability. This can affect not only the “backstage” running of government but also frontline services on which citizens rely, such as healthcare, policing, or education.

What is the evidence?

I demonstrate these lame-duck politics through an empirical study of municipalities in Brazil. In field interviews with bureaucrats and politicians, I had heard about how local governance and public services suffered after an incumbent’s defeat. To more systematically test these ideas, I used detailed administrative data on elections, public employment, and healthcare services in all municipalities in four election cycles. To isolate the causal effect of an incumbent losing office (from other things that may correlate with it such as a declining economy or other governance issues) I leveraged a regression discontinuity design, which essentially compares what happens in municipalities where the mayor barely loses the re-election campaign to what happens in localities where they win.

When a mayor loses re-election, bureaucratic shuffles ensue almost immediately – well before the new mayor takes office. In particular, electoral defeat causes an increase of about 42% in the dismissal of temporary workers, and a growth of about 30% in the hiring of civil servants, in the months between the election and the winners being sworn in.

Interviews, media reports, and heterogeneity analyses suggest that lame-duck politicians use dismissals to improve their compliance with legal rules about hiring, in an effort to avoid prosecution. They also sometimes use civil service hires to limit their opponent’s fiscal capacity to hire their own supporters. Lame ducks’ use of civil service hiring can hurt their opponents because election winners in fact use their discretion to hire as soon as they take office. When the incumbent loses, the hiring of temporary workers increases on average by 99% at the beginning of the new mayor’s mandate. This is in line with previous research that has documented how election winners use public employment to bring into government bureaucrats aligned with them, in contexts as diverse as Norway, Ecuador, and the United States. In some cases, the misalignment between political leaders and high-level bureaucrats can make it harder for them to deliver public services.

The political dynamics of the lame-duck period have serious consequences for the delivery of healthcare services. Detailed administrative data on healthcare delivery shows that prenatal check-ups, medical consultations with infants and children, and immunizations for infants and pregnant women all decline between the mayor’s electoral defeat and their exit from office. These declines, of between 8 and 39%, suggest that lame-duck politics can jeopardize citizen welfare, at least in the short run. Another recent study using a similar design suggests the bureaucratic politics of lame-duck periods increase infant mortality.

What drives these declines in critical healthcare services? The evidence suggests there are a number of factors driving them, including bureaucratic turnover in the healthcare bureaucracy, disruptions to transportation and other material resources, and weakening bureaucratic accountability under lame-duck governments.

While my empirical study focuses on Brazilian municipalities, these patterns are likely not unique to this setting. In the United States, for example, it is common for outgoing presidents to “burrow in” their loyalists into the civil service, or to use so-called midnight regulations to tie the hands of the incoming administration.

What can be done?

These findings on Brazilian municipalities have some important implications for how we think about political turnover in all democracies, and give us some hints on how to protect societies from the costs of electoral accountability.

One way to limit the shortcomings of lame-duck politics is to increase media scrutiny and public pressure on outgoing governments. In my study, wealthier municipalities (which may have stronger societal accountability and bureaucratic norms) experience fewer disruptions in service delivery during the transition period.

Another, more policy-driven solution would be to shorten the lame-duck period itself. That period is long by design in many presidential democracies. Mexico shortened the transition periods by two months through a legal reform in 2014 – a path that could be followed by other countries with a presidential system. In parliamentary systems, the lame-duck period is not defined ex ante; instead, it depends on parties’ success in negotiating a new cabinet. This means the lame-duck period can get extraordinarily long – Belgium famously spent almost 500 days with a lame-duck government. In these settings, legal reforms may reduce the lame-duck period by establishing deadlines or providing incentives for the government formation process.

Electoral turnover is vital for democracy, bringing fresh leadership, renewed energy, and accountability into government. But if we ignore the disruptions of lame-duck politics, these moments of renewal can become periods of dysfunction where public services decline and election losers tie the hands of their successors before they even take office. Strengthening democracy means not just holding fair elections, but also ensuring smooth and effective transitions of power.

© IE Insights.