“Friedman’s article [The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase its Profits] is widely misquoted and misunderstood. Indeed, thousands of people may have cited it without reading past the title. They think they don’t need to, because the title already makes his stance clear: companies should maximize profits by price-gouging customers, underpaying workers, and polluting the environment.”

Alex Edmans, Professor of Finance, London Business School

* * *

Here is a puzzle that has intrigued me as long as I can remember: How on earth did an essay written by a non-expert become the center of attention and the target of vitriol across the globe for over half a century, with apparently no end in sight?

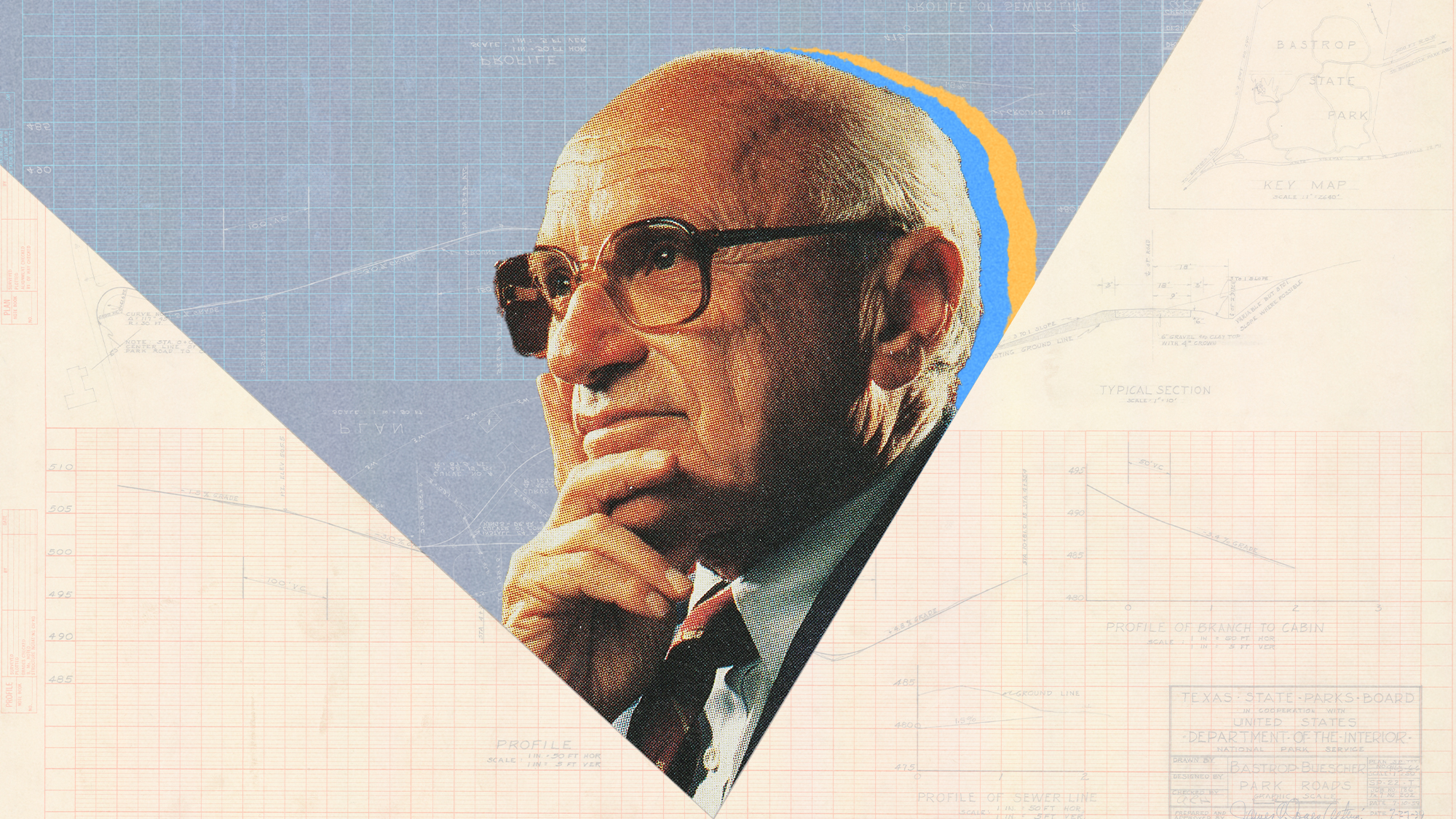

Did I just call Milton Friedman, one of the most influential economists of the 20th Century and the 1976 economics Nobel Laureate, a non-expert? Yes, I did.

Perplexity.ai estimates that Friedman wrote “thousands of pages” of peer-reviewed text in his career, which is beyond impressive. Exactly how many of these pages were on corporate social responsibility? Zero.

Milton Friedman was a neo-classical macro-economist whose fields of expertise included monetary policy, unemployment, taxation, and consumption. He never did research on corporations and corporate governance, and his contributions to the topic consist of about twenty pages of terse, non-peer-reviewed commentary. My prediction is that his 1970 New York Times op-ed “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits” would not have survived peer review. Friedman himself described his remarks on corporate social responsibility as “a fairly cursory survey.”

Nevertheless, Friedman’s argument on corporate social responsibility remains relevant for two reasons. First, the fact that business professionals and academics continue to refer to it suggests the text is worth a closer look. Second, and more importantly, Friedman did actually present four crucial questions that those in corporate leadership positions should consider.

To clarify, scores of people have abused Friedman’s arguments by misinterpreting them to suit their own purposes. While it is appropriate to acknowledge the widespread abuse, I’d rather explore a more positive way of reading his arguments.

* * *

To be sure, the title “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase its Profits” gives us ample opportunity to be offended and stop reading – but let’s take an analytical approach and examine Friedman’s position.

Friedman never actually defined what he meant by profit. Did he think of it in income statement or balance sheet terms? What time horizon did he have in mind? My reading of Friedman is that he must have meant increasing the value of shareholders’ equity in the long run. Given that shareholders are investors (not donors), this objective should not be too controversial. When was the last time you decided to invest your wealth in something without expecting to receive back more than what you put in?

But wasn’t Friedman’s prescription not just to increase but specifically to maximize profits? Those who did not make it past the provocative headline may be surprised that the word “maximization” does not actually appear in the article. In his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman used the term once, but it no longer appears in the 1970 article.

Two further points about maximization merit attention. Most importantly, when economists write about maximization, they really mean something more modest: making decisions that increase firm value over time. Furthermore, the economists’ focus is often not merely on the value of shareholders’ equity but the value of the entire firm; financial economist Michael Jensen, among others, has made this important distinction. The other point is that while the term maximization can be found in the economics literature, it appears only in abstract economic models that rest on simplifying assumptions that are never met in actual decision situations. The notion of maximization is typically invoked merely as a theoretical starting point for academic inquiry, not as a prescription for actual decision making. Friedman surely knew this.

In the world in which we actually live, it is well understood that we are unable to maximize (or minimize) anything. How would you make, say, your diet maximally healthy? How would you minimize the travel time from your home to your office? Even trivial amounts of complexity and the slightest amount of uncertainty rob us of our ability to make optimal decisions. What we do instead is find a solution we can live with and stop there – we don’t even care whether we have reached an optimum or not.

* * *

In its relentless quest for profits, does a manufacturing firm have the right to pollute a town’s water supply because it’s cheaper than proper waste disposal? This might indeed increase profits, but it is an insult to intelligence to suggest that any ethical person would condone such criminal behavior. However, Friedman would have gone even further to point out that pollution also violated his foundational principle of freedom, which he defined as the absence of coercion. He would have considered pollution problematic even if no laws had been broken, that the residents had been coerced into giving up their freedom to choose clean water for themselves would have been sufficient.

It is beyond ridiculous to suggest that DuPont was following “the Friedman Doctrine” when it dumped carcinogenic perfluorooctanoic acid into the Ohio River, contaminating the water supply of the surrounding communities.

Economic scholars Harvey James and Farhad Rassekh noted that Friedman “never advocated the pursuit of one’s interest to the detriment of individuals and society.” Instead, he rejected everything that jeopardized the central objective of “protecting each of us from coercion by our fellow citizens, adjudicating our disputes, and enabling us to agree on the rules that we shall follow.”

* * *

Let me now move on to why Friedman considered the idea that a corporation has social responsibilities problematic. What I call “Friedman’s challenge” can be summarized in four questions, which are found on pp. 133-134 in Capitalism and Freedom. And indeed, page 133 of Capitalism and Freedom is the only instance where I have seen Friedman write about profit maximization. I might suggest that even in this one instance, Friedman could easily have eliminated the term and focused on the relevant question of how the social responsibilities of the corporation are defined. Furthermore, it is important to consider the question in conjunction with the other three questions.

Friedman’s Four Challenges to Corporate Social Responsibility

First Question “If [corporate leaders] do have a social responsibility other than making maximum profits for stockholders, how are they to know what it is?”

Second Question “Can self-selected private individuals decide what the social interest is?”

Third Question “Can they decide how great a burden they are justified in placing on themselves or their stockholders to serve that social interest?”

Fourth Question “Is it tolerable that these public functions of taxation, expenditure, and control be exercised by the people who happen at the moment to be in charge of particular enterprises, chosen for those posts by strictly private groups?”

Suppose that the board of directors is contemplating the allocation of corporate funds to projects that do not meet the company’s minimum required rate of return on investment. What kinds of rules should it set, such that the best interest of the corporation is served? Let us not forget that the best interest of the corporation is an objective the board is legally required to consider in all its decisions.

If the standard hurdle rate is abandoned, then allocating resources to the specific project serves, by definition, non-economic (“social”) interests. Why is this allowed, and who gets to decide which specific social interests qualify for the exemption?

* * *

Friedman’s challenge is best crystallized in the extreme case of projects that create no revenue at all: corporate philanthropy. Let’s say a global corporation channels part of its wealth to finance children’s wards in hospitals. Why hospitals? Why children’s hospitals? Which specific hospitals, and in what geographical locations? Helping children in need is a noble and worthy cause, but instead of hospitals, why not donate, say, to humanitarian relief operations in countries such as Nigeria and Sudan, both listed by Save the Children International as being among the worst conflict-affected countries in which to be a child.

Friedman’s position was that the portion of corporate wealth that cannot be allocated to productive purposes has to be returned to its rightful owners, the shareholders. If the wealth is instead given away, the corporation is effectively taxing its shareholders.

There are two counter-arguments. One is that the amount given away is insignificant. Fine, but in that case, let us be specific about the maximum amount of your wealth that someone else can give away without your consent. The other counter-argument is that corporate philanthropy improves the corporation’s reputation and ultimately serves the corporation’s financial interests; therefore, the hurdle rate is not abandoned but merely suspended. If that is the case and the ultimate motivation for philanthropy is financial, then let us be open about it.

* * *

The greatest source of confusion around Friedman’s article, as I see it, is that Friedman used imprecise and unnecessarily provocative terminology to present ideas that, upon closer inspection, aren’t as controversial as they might first seem. Boards and executives in the modern corporation have much discretion in deciding how to allocate company resources. Friedman invited us to acknowledge the fine line between deciding on someone’s behalf and taking away someone’s right to choose, particularly in situations where those who make decisions act as someone else’s legal fiduciaries.

* * *

To be absolutely clear, I’m in no way suggesting that shareholder centrism isn’t a problem or that we have successfully eliminated short-termism from the modern corporation. Rather, my point is that it is misguided and unreasonable to think that an op-ed written by an academic over half a century ago could have contributed to these problems in any major way. Would the corporate world be any different had Friedman not written his op-ed? It’s doubtful.

I find legal scholar Brian Cheffins’s analysis of why companies focus on shareholders more convincing. Cheffins maintained that the shareholders-first mentality “occurred due to an unprecedented wave of hostile takeovers rather than anything Friedman said and was sustained by a dramatic shift in favor of incentive-laden executive pay.” Cheffins’s Washington University Law Review article was aptly titled, “Stop Blaming Milton Friedman!”

© IE Insights.