Last week, news was out that India’s economy has surpassed that of its former colonial master. Machiavelli once said that “nothing is so weak and unsustainable as a reputation for power which is not based on one’s own strength.” The recently departed Queen Elizabeth II saw the United Kingdom transition from an empire to a major post-colonial power, though this political shift also brought about substantial economic changes.

A series of questionable policies in the 1960s resulted in the UK having to ask for a bailout from the International Monetary Fund in 1976. The UK economy grew strongly over the next two decades, driven partly by London’s sound position as a global financial hub with significant exports of financial services to other EU countries, and by attracting an extraordinary pool of talent.

The financial crisis of 2009 was a turning point in this sense.

Like so much else, growth also leads to imbalances. While London became a thriving metropolis, the rest of the country lagged in terms of development and, despite exporting financial products, the British economy was not competitive enough to export more services and goods than the ones it imported, running up constant trade deficits. In part, the imbalance between London’s prosperity and the weaker development of the rest of the country gave rise to animosity towards the capital, which materialized in Brexit and which different governments are attempting to address with “levelling up” strategies.

If we analyze the country’s economic future, there are clear threats:

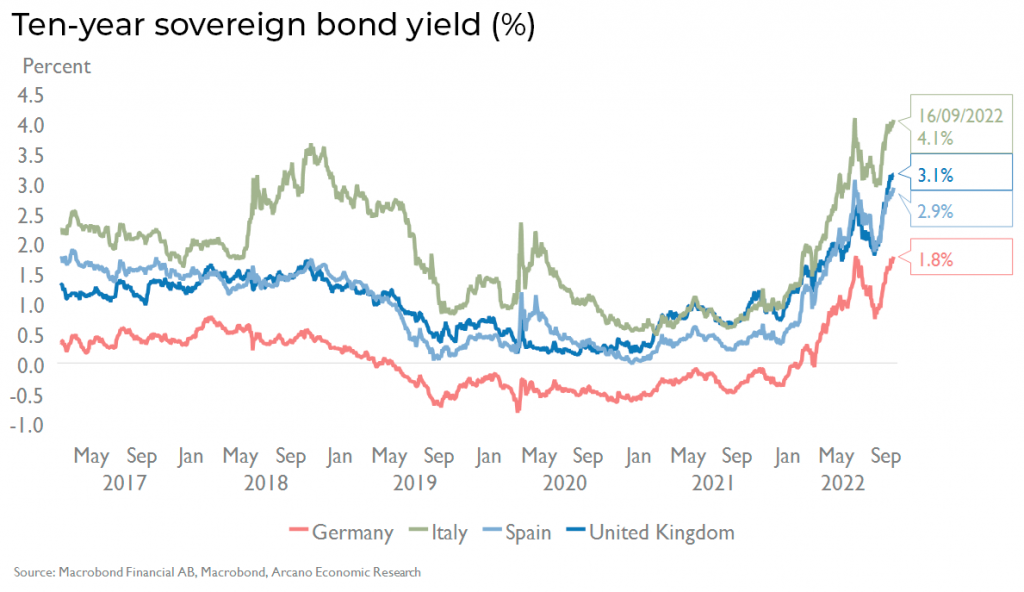

First, the UK will be hit harder by the crisis brewing in Europe. The extremely weak pound will make imports even more expensive, compounding the problem of high inflation fuelled by high energy prices. The Bank of England is steadily raising interest rates to tackle high inflation, which has pushed long-term interest rates to 3%, their highest level in years. Inflation is also taking its toll in the form of lower real consumption (wages are not keeping pace with inflation, constraining the amount of goods and services that are consumed. As a result, retail sales are already floundering, with consumer confidence at record lows). Higher interest rates will also undermine future economic growth, in addition to having already triggered falls in house prices. The economy is set to enter a technical recession in 2022 and stagnate in 2023 in the best-case scenario.

Second, the new government seems to have embraced a strategy of tackling economic challenges by increasing public spending and announcing lower taxes. For example, the new Prime Minister’s recent promise to cap household energy bills and pay the difference with public money, a whopping 4.3% of GDP, without clarifying the sources of revenue, will inexorably lead to higher deficit levels.

Third, as a result of the situation above, the UK is already facing a huge current account deficit, which stands at almost 8% of its GDP (first quarter data), and the second largest in the world in dollars after the USA. We should remember that Spain’s debt crisis was triggered by a deficit of 10% of GDP, which was the second largest in the world in dollars at that time. It is true that the UK has its own currency, while Spain shares the euro, but this can be just as much a threat as it is a source of opportunity. This is why some banks have warned that the UK could end up facing a balance of payments problem similar to that of an emerging country (and is what happened in 1976, as we have already explained). This strikes me as being somewhat of an overstatement (the trade gap will improve when energy prices return to normal from 2025 or 2026 onwards) but, in any case, this interim scenario leads us to the next point.

Fourth, the UK needs to attract capital on an ongoing basis to finance such a huge deficit. This can be achieved with good economic basics, including healthy GDP growth and sound public finances. However, the context points in the opposite direction. Thus, funding a huge current account deficit when there is a strong headwind blowing suggests that the currency will continue to depreciate and/or long-term interest rates will rise further. Both of these factors will threaten future growth, creating a vicious circle.

In the spring of 2007, I read a brilliant article by Martin Wolf which claimed that the prosperity of the Spanish economy was deceptive, as it was based on huge imbalances, especially the historical current account deficit, which created the effect of “living beyond one’s means.” I remember that the accompanying cartoon showed a bullfighter wielding a cape and a bull charging at him with the word “deficit” emblazoned on its side.

If we look at the United Kingdom, the bull is already running.

A version of this article was published in Spanish in El Confidencial.

© IE Insights.