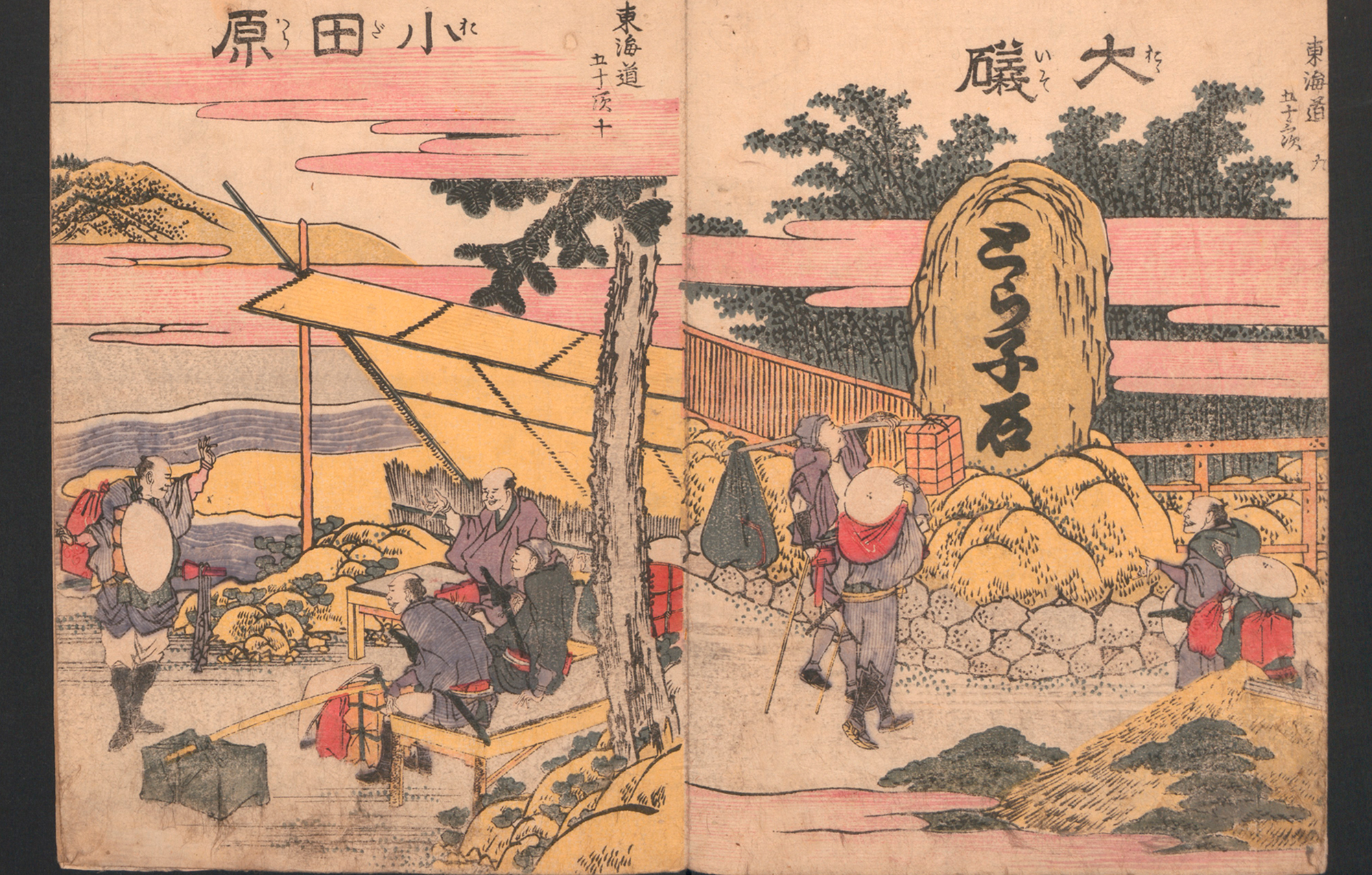

Main image: Fifty-three Stations on the Tokaido Road by Katsushika Hokusai

On the wall of my office, I have two pictures. They are not of my family. I have many of those on my phone and around my house. Every time I visit a lock screen on a mobile device, it reminds me why I get up in the morning because for me, like so many others, family is everything. The pictures on my office wall, however, serve a different purpose. They are there to remind me not why I do what I do, but how to do them.

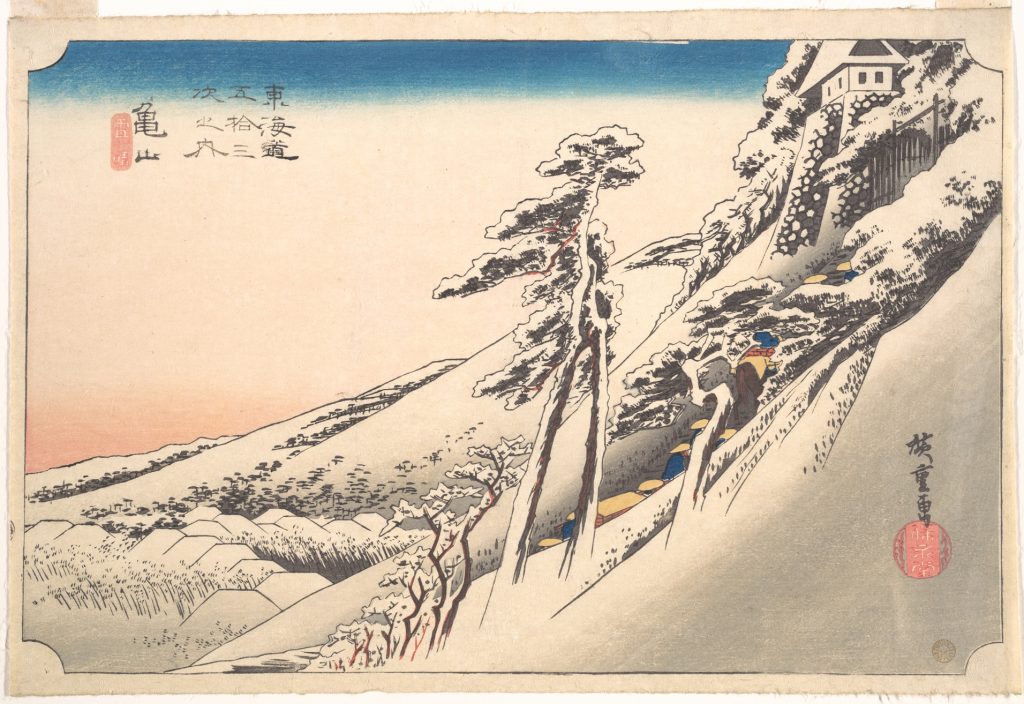

The pictures on my wall are two prints of exactly the same thing, according to their titles: Kameyama. For me they represent the team and the individual.

Now, for those without a passionate interest in the world of Japanese culture, the title of these works might not mean much, but those who have studied the nation and its history will recognize it as a station on the Tokaido road. This eastern sea route was the most important of Japan’s Edo period (1603-1867) and the journey between Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and Kyoto was made on foot for centuries until cars and eventually the Tokaido line was created for the Shinkansen bullet train.

When people walked the Tokaido road, there were stations at which to stop and relax, buy food, perhaps sleep, or even, if rich enough, rest their horses and mules. In 1832, the artist Utagawa Hiroshige traveled the road and soon after produced a series of paintings of each of these 53 stations, one of which is on my wall.

This is art made by the people, for the people.

Hiroshige’s work is very much about the power of the team and the print I gaze upon in my office shows a group of men walking together on their journey either to or from Kyoto. However, it is not the actual team depicted by Hiroshige that interests me, but the actual production of work. Ukiyo-e is a genre of art from this period that included woodblock prints and paintings and required a massive team of artists, craftsmen, and workers to come together to produce each piece. It is an absolute entrepreneurial exercise – one that does not even begin with Hiroshige – that cannot function without each person playing their part. The artist would first have to be commissioned and that person would need someone who could manage and run the massive process of taking the artistic vision and turning it into a piece of work that could be replicated and distributed. This publisher, this chief operations officer if you will, pulls all of the strings – the first being the one that gets a painting from the artist himself.

Kameyama by Utagawa Hiroshige

Ukiyo-e prints usually went through multiple editions, undergoing subtle (or big) changes before being completed and, once finalized, the woodcuts would often be recut and recirculated. These reproductions were not done by the artist but by a team of several people. The tracer lays the different sections of the image onto woodblocks of a hard cherry wood and then the carver starts to let the image take shape. A print of this kind would have several colors and thus, for each layer of color, a new block of wood would need to be carefully carved in order to allow the printing process to bring in the varying layers of trees, sky, people, animals, and more. It was – and still is today – a process in which artisan and artist work hand in hand.

Then comes the production. A special paper, called washi, is made by hand – as it still is today – from the mulberry bush. Then inks are mixed and the bursts of color in these beautiful images are thanks to a very particular alchemy and skill. To this day, a trip to an ink store in Ginza can overwhelm the senses, so varied are the number and type of creations. Finally comes the printing, a “skills job” that requires the ability to combine all assembled elements: the paper, blocks, inks, design. Precision and care are needed in this step in order to ensure that the publisher will later be able to produce multiple copies before the blocks wear out.

Then the images are sold. Cheaply. These are some of the greatest artists in history (think Hokusai and his iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa) and their work would have been procured in 1834 for the price of a bowl of noodles. Even today an original or subsequent printing from the period can cost as little as $100. This is art made by the people, for the people. It is a manifestation of teamwork, entrepreneurship, ingenuity, and skill – each operating at the highest level.

Next to the Ukiyo-e print on my wall is another Japanese print, one from the 1960s and 1970s by Junichiro Sekino who worked in the style of Sosaku Hanga. In this genre, the artist did everything: the publishing, painting, carving, and printing. The work on my wall is Sekino’s own interpretation of the Tokaido road, also titled Kameyama. Instead of the people struggling against the elements as was depicted by Hiroshige centuries ago, Sekino’s print renders a door to a courtyard, a bright red and orange wall that is reminiscent of Mark Rothko, his contemporary over the Pacific, topped with a traditional roof. In fact, this was part of how Sekino worked. He took stylistic cues from other artists — the straight-edged elements of Mondrian, the color palette of Van Gogh, and even the compositional structures found in some of Hokusai’s most famous works are evident in his pieces.

Kameyama by Junichiro Sekino (left) and No.5/No.22 by Mark Rothko (right)

Kameyama by Junichiro Sekino (left) and No.5/No.22 by Mark Rothko (right)

Sekino wanted control of his vision, but because he was working in a type of art that traditionally entailed multiple members of a team working together, he worked with certain restraints like he might not be a proficient painter or have the best carving skill, or printing skills. The result is that his work is unique. Copies of his prints often differ in shading, hue, and even markings. His style is in direct contrast to the more precise Ukiyo-e prints.

Despite the artwork, my office is not in Japan. However, I have been fortunate to work in many places in the world, including China, the Middle East, the UK, and now Spain. These prints on my wall serve to remind me of the lessons I have learned about just how vital a team can be and, also, how the individual must not be sacrificed. Both approaches are valid in everything that we do and both can turn out work that is vibrant, beautiful, poetic, and meaningful.

We must never hope for carbon copies coming out of colleges and schools.

In regards to education, these two approaches are essential for a student’s learning journey. First comes the work of the team and the assembly of expertise – similar to the creation of Hiroshige’s work – to ensure precision and clarity of purpose of the education. This is where a top team of teachers, curriculum designers, and academic professionals come together to develop an educational program with just the right quality and content to allow students to develop their skills and intellect.

Then, building upon this, comes the moment when the students reach out on their own and begin to take ownership of their education and their future – in much the same way Sekino did – perhaps not perfectly but uniquely and with personal expression and beauty. We must never hope for carbon copies coming out of colleges and schools but students who have the tools and ambition to take control of their own lives, who will paint their own picture, tell their own story.

Education is like Hiroshige’s Kameyama. Controlled and precise, giving students the tools – ambition, teamwork, collaboration, resilience, creativity, the ability to spot and solve a problem – that students will eventually use to create their own Kameyama, as Sekino did. To do this, students – well, all of us throughout our lives – must be constantly reading, absorbing, watching, producing and trying out different mediums like film, radio, writing. These experimentations are what help people in general and young students in particular become better learners, better students, and eventually better teachers.

It is not only about what happens in the classroom. It is what happens each day on our own Tokaido road. It is our job as educators to provide the space, encouragement, and support for students to try new things and find their way forward: to learn how to paint with oils and sculpt with papier-mâché, to speak another language well and speak another just well enough to get by, to express themselves in writing and express love through cooking for friends and family, to understand that kindness will always win and that greed does not, to develop the ability to begin a conversation with someone new and to hold a discourse with someone of an opposing view, to learn how to make someone feel welcome with and without words. Most of all, we want them to learn how to express their unique selves and, importantly, their hope for the future.

© IE Insights.