Sharia is a word or term that we usually associate with war or violent events. This means that for non-Muslims, especially in the West, it rarely elicits positive sentiments, as it tends to evoke images of punishment linked to religious extremism or to attitudes that we consider unbecoming of a Western state governed by the rule of law. But, what exactly is Sharia?

Anyone who is remotely aware of the fact that we live in a global, highly diverse world can appreciate the need to understand the concept of Sharia – not only because it lends insight into a growing community but also because it allows for engagement in highly topical debates such as the management of diversity and the respect for religious freedom. However, above all, an understanding of Sharia helps to improve coexistence between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Sharia (in Arabic, شريعة إسلامية, šarīʕah al-Islāmīya, ‘way or path of Islam’) is the body of Islamic law. Yet, it is not just a corpus juris civilis. Instead, we ought to consider Sharia as a wide range of ethical and moral principles drawn from the Koran (the holy book of Muslims) and the practices and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, known as Hadith. These broadly encompassing principles are interpreted by jurists to propose specific legal rulings and moral prescriptions.

The body of these legal rulings that emerge from the interpretation of Sharia is commonly known as Islamic law or “fiqh” in Arabic. We must therefore bear in mind that Islamic law is the result of human intellectual activity and, by definition, it evolves and is fallible. It is clearly not taken by Muslims as the word of God, as the Koran is understood to be, but is instead something created by people who interpret the word of God and the actions and sayings of the Prophet.

There is a clear distinction between these two concepts: Sharia itself and the conversations that aim to understand Sharia, which is Islamic law.

Professor Rumee Ahmed of the University of British Columbia makes this distinction clear, in his book Sharia Compliant: A User’s Guide to Hacking Islamic Law with the argument that “The difference between Sharia and Islamic law should always be kept in mind. In shorthand, Sharia is the divine ideal, and Islamic law is a human attempt to capture the ideal. The distinction is crucial.”

It is perhaps interesting to briefly explain the history of Islam in order to understand how Sharia emerged. The Prophet Muhammad or Mohammed, the founder of Islam, was born in 570 AD in Mecca, now Saudi Arabia. (His full Arabic name is Abū l-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd Allāh ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hāšim al-Qurayšī, ابو القاسم محمد ابن عبد الله ابن عبد المطلب ابن هاشم القريش and is often transcribed literally in English as Mohammed.) According to Islam, God revealed the Koran to Muhammad when he was 40 years old, in 610. Therefore, the first Muslims could turn to him to resolve any concerns and to follow his example and guidance. But after Muhammad and his contemporaries disappeared, people continued to need answers and precepts for many situations. These precepts and principles were brought together in a system, along with specific rules in the Koran and Hadith, so that people could find answers to their doubts.

It must also be understood that those who put together the original interpretations of Sharia also included other things, such as the common practices of their time and the cultural norms in force in their region of the world. Therefore, we should not think of Sharia as a legal system, but rather as a set of Islamic principles to help guide people in situations that require new responses, and bear in mind that these common cultural practices pertain to a specific time and place in history.

Traditionally, many Muslim rulers have tried to turn Sharia into law. They first had to decide which rules should be law, and then try to use interpretations of Sharia to show people that these laws were Islamic. Additionally, it’s important to remember that the first Islamic societies were not governed by Islamic law but by caliphs (coming from the Arabic word khalifa, meaning “representative,” caliph is a term that was used to denote the supreme leaders of Islamic governments until 1924) and then governed later by kings and emperors. These rulers often mixed Islamic ideas with secular rules that were already in force or were common practice.

Islamic law is therefore always based on someone’s interpretation of Sharia (which is an interpretation of the Koran and Hadith). Thus, Islamic law can mean different things in different places and at different times in history.

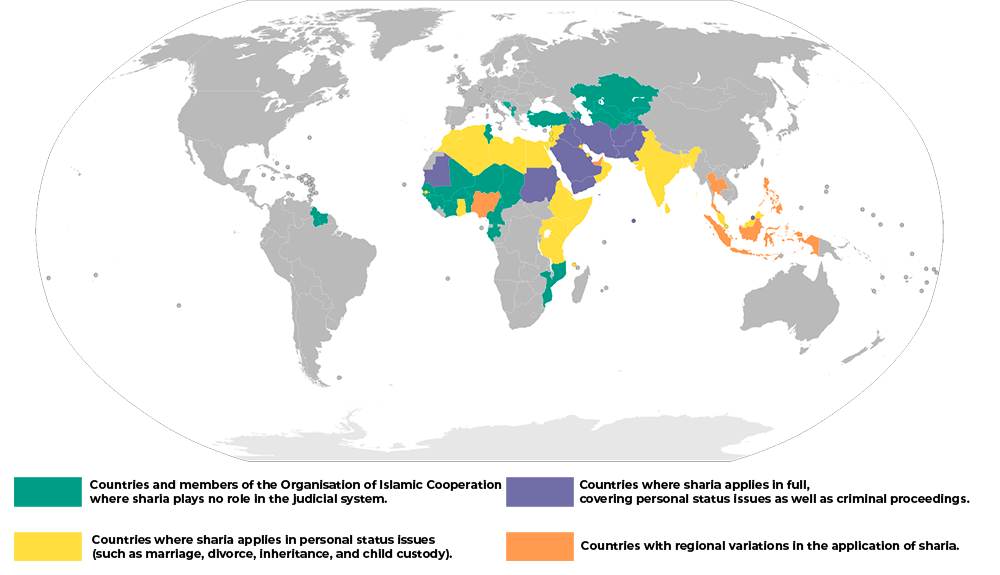

One of the questions that most confuses or arouses curiosity in the West is whether Sharia is the law that prevails in Muslim countries and how its implementation differs from one country to another.

In Sunni Islam, which is the religion’s largest branch, there are four schools of Islamic law, all of which are valid and orthodox in their respective jurisdictions, illustrating the tremendous diversity in Islam and the recognition of differences of opinion as being legitimate. (Approximately 90 percent of the world’s Muslim population are Sunni. Sunni Islam is essentially divided into four orthodox schools of law: Hanafi, Shafi, Maliki, and Hanbali. Each school has its own highly developed doctrines.) Normally, Islamic legal rulings apply mainly in the area of personal and family law, governing issues of marriage, divorce and inheritance, among others. It is important to grasp the fact that civil law in most Muslim countries is based on modern Western legal systems which, in some ways, is a legacy of the period of European colonization in much of the Islamic world that began in the 19th century.

Another of the issues that arouses debate in the West is whether Sharia law undermines women’s rights. Islamic law considers men and women to be morally equal in the eyes of God, yet their rights and obligations (particularly economic ones) are not identical but seen, instead, as complementary.

Islam is diverse and one of the elements behind its success has been precisely its ability to adjust across cultures and peoples, and this is something that, quite frankly, clashes with the more established stereotypes held by the West.

There is probably more plurality in Islamic law today than ever before. Technology, digital transformation, and globalization also play a role in this regard, giving Muslims everywhere, and particularly those living in Western countries, immediate access to the opinion of Islamic scholars on any issue. This phenomenon is known as “Sheikh Google,” and it is particularly relevant for the younger generation, who seek answers to their questions on faith and Islamic law on the web and in social media. This, of course, brings with it problems of control and legitimacy. There is no doubt, therefore, that digitalization and the so-called fourth industrial revolution play a part in this issue of plurality.

Finally, it is important to note that properly qualified scholars may issue fatwas (Arabic, فتوى fatwā; plural, فتاوى, fatāwā), or statements of opinion, on particular matters of Muslim life. A fatwa is a legal ruling in Islam, issued by a specialist in religious law on a specific issue, usually issued to settle a matter in which fiqh, or Islamic jurisprudence, is unclear. A scholar who is suitably qualified to issue a fatwa is known as a mufti. However, a fatwa is only binding for the issuer and those who have bound themselves to it. Indeed, they can sometimes be contradictory on the same issue, and in the absence of some sort of centralized Islamic priesthood, there is no unanimously accepted method of deciding who may issue a fatwa and who may not, which further complicates the matter.

In short, the debate and knowledge of Sharia and Islamic law is both complex and exciting. It directly affects a large part of the world’s population, including in Western societies and a large percentage of young people, all against a background of continuous change and technological revolution, none of which can be ignored.

© IE Insights.