Nearly a century ago, the League of Nations took its first steps toward international disaster cooperation with the creation of the International Relief Union (IRU). Its bold vision – to provide coordinated relief, promote prevention, and foster global solidarity – laid a foundation for international disaster law. However, the IRU faltered, leaving an unfinished legacy as conflicts and evolving global challenges outpaced its framework.

The United Nations General Assembly now has an opportunity to revive that vision. On 6 December 2024, it adopted Resolution A/C.6/79/L.16, initiating negotiations for a legally binding treaty to protect people in disasters. This treaty builds on the International Law Commission’s 2016 Draft Articles and incorporates the lessons of prior UN efforts, such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030.

Crucially, it seeks to address not only natural disasters but also the increasing overlap with armed conflicts and the complexities of International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

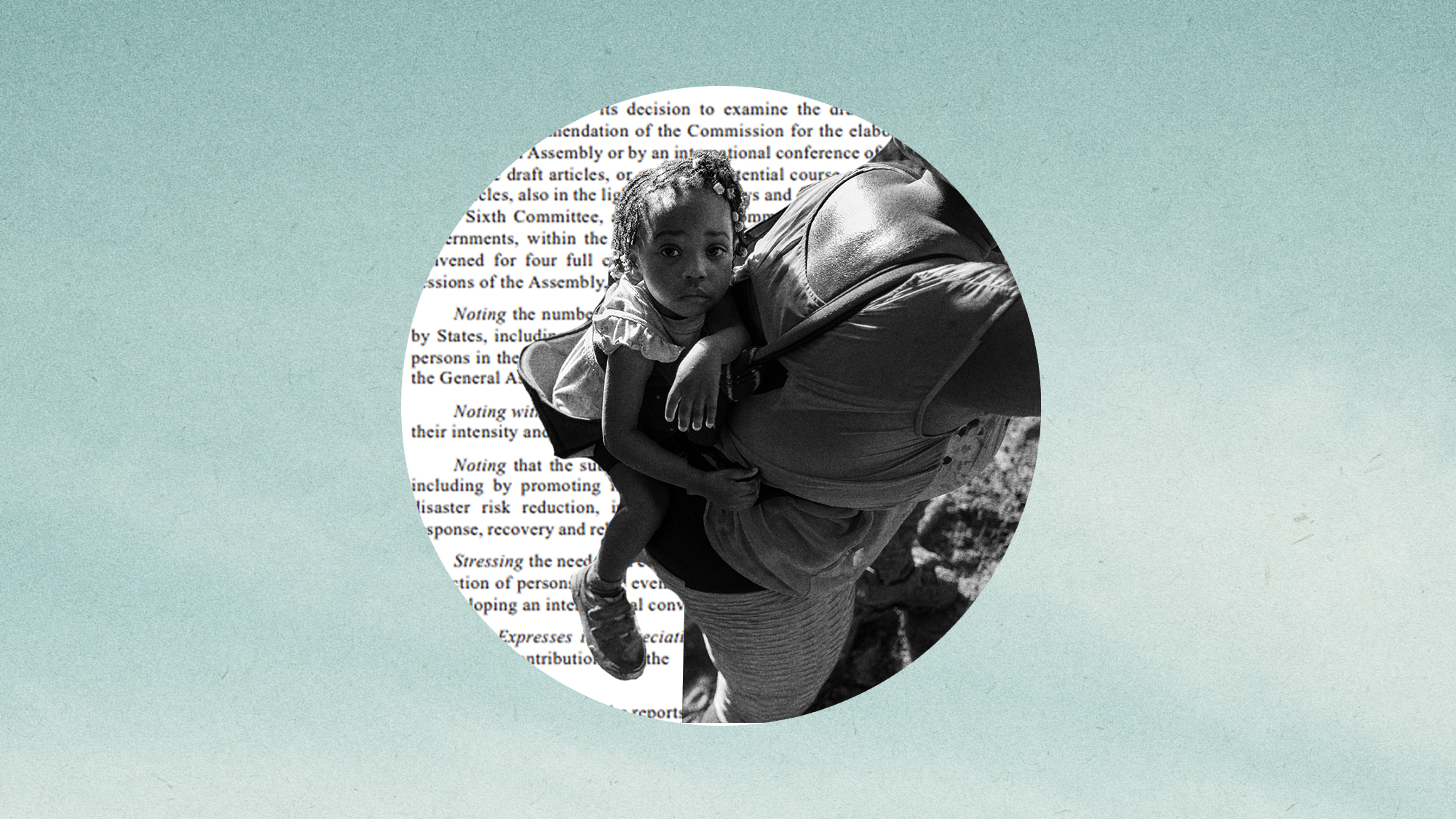

This nexus is critical. The ILC Draft Articles, while primarily focused on disasters, acknowledge that the principles of human dignity, human rights, and international cooperation resonate in both disaster and conflict scenarios. This overlap between disasters and armed conflicts, such as floods displacing vulnerable populations in war zones, creates dual challenges that existing frameworks often fail to address.

Disasters in conflict areas, for instance, may see relief efforts hindered by the rules of sovereignty or the prioritization of military objectives over humanitarian needs. As this treaty evolves, bridging the gaps between disaster law and IHL must remain central.

As the commentaries of the draft indicate “in situations of ‘complex emergencies’ where a disaster occurs in an area where there is an armed conflict, the rules of international humanitarian law shall be applied as lex specialis, whereas the rules contained in the present draft articles would continue to apply ‘to the extent’ that legal issues raised by a disaster are not covered by the rules of international humanitarian law.”

The stakes are high. From floods and wildfires exacerbated by climate change to the compounded suffering caused by disasters in war zones, the need for cohesive international action has never been greater. If adopted by 2027, the treaty could mark the centennial of the IRU by finally fulfilling its promise: a unified, effective framework to protect lives in times of crisis.

The question is not whether the world needs this treaty, but whether we can afford to delay it any longer.

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami revealed a tragic truth: the international community’s legal response to disasters is fragmented, inconsistent, and often inadequate. The ILC’s Draft Articles sought to change that by creating a unified framework addressing the entire disaster cycle – prevention, response, and recovery.

At the heart of these articles is a delicate balancing act: respecting state sovereignty while ensuring international cooperation. For instance, the ILC dictates that offers of assistance cannot be refused “arbitrarily”, a crucial safeguard when political considerations threaten to override humanitarian needs. But what constitutes “arbitrary” refusal remains up for debate, and that ambiguity could undermine the treaty’s effectiveness.

Meanwhile, disasters have grown more complex. Armed conflicts and natural disasters often overlap, exacerbating humanitarian crises. For example, floods in conflict zones may render populations doubly vulnerable, complicating relief efforts under existing IHL frameworks. Relief coordination must bridge these challenges by ensuring that disaster response operates alongside protections afforded in armed conflicts.

Moreover, the principle of human dignity, enshrined in both IHL and the Draft Articles, underscores the need to harmonize disaster law with conflict rules. As IHL governs armed conflict, it recognizes that disasters occurring in war zones often require dual compliance – respecting sovereignty while safeguarding humanitarian imperatives. The ILC’s commentary on Draft Article 18 clarifies that disaster rules should fill gaps not addressed by IHL, ensuring a comprehensive approach to protecting affected populations.

Let’s think about the Tampere Convention on Telecommunications, which streamlines aid by removing bureaucratic barriers in case of disaster. Why should similar provisions not apply universally to disaster response, including in conflict-affected areas?

As negotiations begin, the challenges are clear. States must overcome three critical hurdles to make this treaty meaningful:

1. Clarifying the Definition of a Disaster.

The current definition excludes political and economic crises, which aligns with international norms. However, greater clarity is needed in defining disasters in areas affected by armed conflicts. Disasters and conflicts often overlap, with populations in conflict zones suffering dual vulnerabilities. For instance, natural disasters like earthquakes or floods can exacerbate the humanitarian crises already present in areas of armed conflict, where displacement, famine, and infrastructure destruction are prevalent.

International Humanitarian Law (IHL) addresses the protection of populations during conflicts, emphasizing the principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence. Yet, disasters in conflict zones reveal gaps where neither IHL nor disaster-specific frameworks sufficiently address the compounded vulnerabilities. As noted in the ILC’s commentary on Draft Article 11, international cooperation and coordination become paramount in these scenarios, especially when sovereignty claims by parties to the conflict hinder relief efforts.

The integration of disaster law and IHL in defining a disaster’s scope must ensure that no population – whether affected by conflict, disaster, or both – is left without legal protections. By incorporating IHL principles, the treaty can bridge these gaps and reinforce the humanitarian obligations of states and non-state actors in disaster-prone conflict zones.

2. Ensuring Consent Doesn’t Become an Obstacle.

The principle of state consent, a cornerstone of international law, must be balanced against humanitarian needs. While sovereignty is vital, history has shown that rigid adherence to this principle can lead to dire consequences when aid is delayed or blocked due to political disputes. For instance, past emergencies, including in conflict zones, have seen affected states prioritize political or military objectives over the timely delivery of humanitarian relief. This has compounded suffering for vulnerable populations, particularly in areas where natural disasters occur during ongoing conflicts.

To overcome this challenge, the treaty must introduce mechanisms that prevent the arbitrary refusal of aid. Drawing from models like the IAEA Convention, which obliges states to accept assistance during nuclear emergencies, the treaty can establish predefined obligations for states during disasters. These obligations could include mandatory acceptance of aid when refusal would result in significant harm or loss of life. Additionally, the treaty can incentivize compliance through international peer reviews or sanctions for non-cooperation. This balance of consent and humanitarian necessity is essential for ensuring aid reaches those who need it most, especially in politically sensitive regions.

3. Creating Accountability Mechanisms.

A treaty without teeth is just paper. For this agreement to succeed, it must include robust tools for accountability. Dispute resolution mechanisms, such as arbitration or adjudication, should be embedded within the treaty to address disagreements between states or non-state actors regarding the provision of aid. Periodic reviews of compliance by an independent oversight body could ensure that states uphold their obligations under the treaty.

Furthermore, oversight bodies should have the authority to monitor and report on the implementation of disaster response measures, identifying gaps and recommending improvements. Drawing inspiration from the Chemical Weapons Convention, the treaty can incorporate a system of state parties that convenes regularly to assess progress, share best practices, and address emerging challenges. This participatory approach fosters accountability while encouraging collaboration among nations.

Finally, public reporting mechanisms should be mandated to enhance transparency and build trust. By requiring states to publicly disclose their disaster preparedness plans and response measures, the treaty can promote accountability not only to the international community but also to the affected populations. These combined measures will ensure the treaty remains a living, effective instrument for protecting lives in disasters.

Disasters do not respect borders. They do not wait for politicians to debate the finer points of sovereignty. When hurricanes wipe out entire cities, when floods displace millions, when pandemics overwhelm healthcare systems, the world must act – and act swiftly.

A universal treaty on the protection of persons in disasters is not just a legal necessity. It is a moral obligation. By closing the gaps in international law, we can ensure that when the next disaster strikes, no community, no nation, and no person is left behind.

The world failed to act in 1927. We cannot afford to fail again.

© IE Insights.