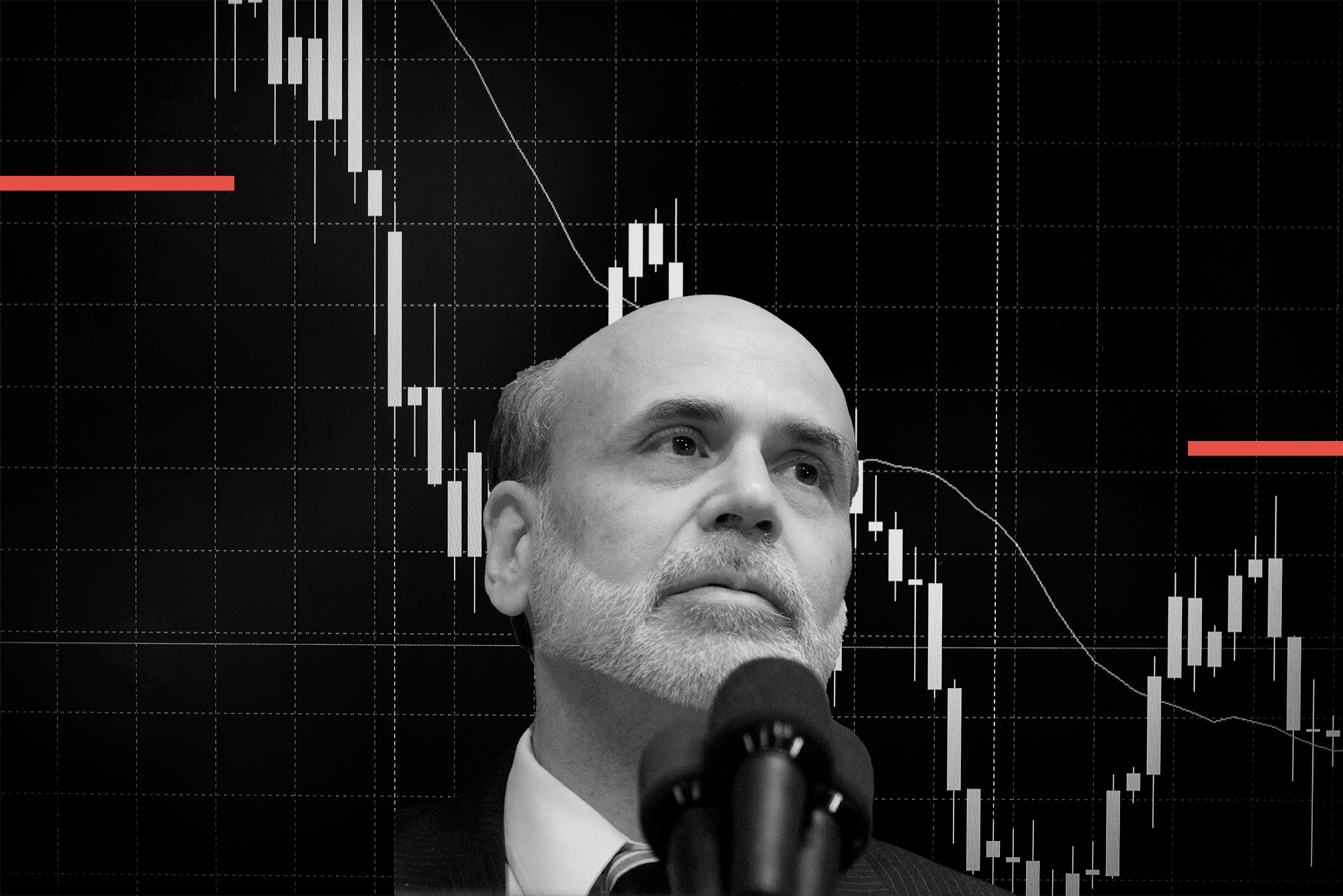

Much like the Roman god Janus, who is depicted with two faces, Ben Bernanke had two outlooks on the economy: that of a theoretician (academic researcher) and that of a pragmatic economist (Governor of the US Federal Reserve). Both of these facets were taken into account when he was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, which he shares with Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig.

As a researcher, Bernanke conducted a major study on the Great Depression of the 1930s, the worst economic crisis in modern history, entitled “Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” The Swedish committee stated that this article demonstrated that the Great Depression “became so deep and prolonged in large part because bank failures destroyed valuable banking relationships with businesses and depositors, leaving significant scars on the real economy.”

Indeed, Bernanke puts the spotlight on financial intermediaries when it comes to addressing the causes of this crisis. These market players possess highly relevant information about the behavior of their clients, which they build up over years of work and is not easily transferable to other organizations. This is why, during the Great Depression, banking issues hampered the reconnection between those who needed access to loans to invest and those who had savings to put into deposits.

Through his research article, Bernanke scientifically demonstrates the coincidences in terms of time between financial crises (especially bank failures in the United States) and the malfunctioning of the U.S. economy. Bernanke’s analysis was based on time-series regressions correlating the fall in industrial production with bank failures.

The Origin of the Great Depression

Other economists, notably Bernanke’s fellow Americans Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, stated that the Great Depression was due to monetary policy errors. In their view, the bank failures at the time were a consequence of the economic crisis. The thesis that Bernanke put forward differs from that of Friedman and Schwartz. Bernanke concluded that it was the banking crises, and not the lack of money, that caused the dramatic fall in manufacturing and thus triggered the Great Depression.

Moreover, Bernanke pointed out that the amount of money available did not shrink so substantially as to cause a depression. He does agree with Friedman and Schwartz that money was an important factor in the 1930-33 period but he is skeptical about whether it fully explains the connection between the financial sector and overall production. Bernanke argues that monetary forces were, at most, only part of the problem. This is what prompted him to study a non-monetary channel through which an additional impact may have caused the Great Depression. Proof of this conviction is precisely the title of his journal article.

It is in this article that Bernanke explains how the U.S. financial system experienced one of the most difficult and chaotic situations in its history from 1930-1933 (masterfully reflected in Frank Capra’s film It’s a Wonderful Life). There are a number of episodes, following the chronological order of the different financial crises. First, an apparent attempt at recovery from the 1929-30 recession was stalled at the time of the first banking crisis (November-December 1930). Secondly, the incipient recovery degenerated into a new slump during the mid-1931 panics. And, finally, the economy and the financial system both reached their respective low points at the time of the bank “holiday” of March 1933. These three rounds of bank failures culminated in the temporary shutdown of the banking system. In fact, when Franklin D. Roosevelt took office as President of the United States in 1933, he ordered the banks to close and organized a bank rescue plan. Therefore, “only with the New Deal’s rehabilitation of the financial system in 1933-35 did the economy begin its slow emergence from the Great Depression.”

The 1930-33 stock market and banking crisis can be summed up in three points:

- The New York Stock Exchange crash in October 1929 reduced the stock market wealth of families by more than 10% and, as people’s wealth decreased, triggered a “poverty effect.” As a result, consumption fell, especially of durable goods. Investment also slumped, due to reduced consumption and greater uncertainty among companies about the future of the economy. This drop in demand and investment generated excess supply, which drove the prices of goods and services down. The result was a long period of deflation.

- The excessive hike in interest rates led to defaults on loans with all types of companies going bankrupt. It must be remembered that the main banks had granted loans at very low interest rates prior to 1930. However, with the wave of bank failures, many banks were no longer able to grant loans, so other healthy banks began to grant loans at higher rates. This had a direct impact on many companies, and especially small businesses, forcing them to close down.

- There was a malfunctioning of financial institutions during the early 1930s. As Bernanke writes, the two major components of the financial collapse were the loss of confidence in financial institutions, primarily commercial banks, and widespread insolvency of debtors (companies and households). The resulting high rates of default caused problems for both borrowers and lenders. The ‘debt crisis’ touched all sectors. Many companies that had asked for loans now had to survive without them.

The Great Depression had devastating consequences. Between 1929 and 1933, U.S. GDP plummeted by over 25%. In 1933, industrial production was 46% below its 1929 level. In turn, the dramatic drop in production led to a sharp increase in unemployment, which rose from 3% to 25%, i.e., around 13 million people. To make matters even worse, many employees were forced to work part-time and thus received significantly lower wages. Finally, during this period there were systematic cuts in prices, nosediving by 30% and causing severe deflation.

The Deflationary Spiral

These price cuts and the consequent collapse in companies’ sales revenue led to a decrease in their profits or an increase in their losses. Bernanke writes: “Aggregate corporate profits before tax were negative in 1931 and 1932, and after-tax retained earnings were negative in each year from 1930 to 1933. But the subset of corporations holding more than fifty million dollars in assets maintained positive profits throughout this period, leaving the brunt to be borne by smaller companies.” This led to a significant upsurge in unemployment.

In turn, lower employment reduced the wage bill and, by extension, household spending power. Lower consumption led to a drop in business sales and, as a consequence, to increased losses. As prices continued to fall, consumers shelved their purchasing decisions (especially for durable goods) in the hope that prices would fall even further. This shrank turnover and business investment even further. These developments continued to feed the vicious cycle of declining employment, lower consumption, further price cuts (in an attempt to sell more), and thus even greater economic decline.

When panic and deflation set in, people believed they could avoid further losses by staying away from banks.

In addition, as this deflationary process worsened, it became increasingly difficult for companies to repay their bank loans. While loans maintained their book value, corporations’ ability to meet their repayments diminished. Many companies left the banks with significant rates of default because they did not repay their loans. Bernanke gives the example that, “because of the long spell of low food prices, farmers were in more difficulty than homeowners. At the beginning of 1933, owners of 45% of all U.S. farms, holding 52% of the value of farm mortgage debt, were delinquent in payments.”

In response to the insolvency scenario, banks reacted by tightening their lending requirements, which in turn led to fewer loans and a deeper financial crisis, severely damaging the economy.

The Perverse Mechanics of Panic

Meanwhile, citizens who had savings accounts in banks began to panic about the prospect of not being able to recover their money. Banks had to sell some of their assets (bonds, stocks, real estate) at fire-sale prices to be able to meet these withdrawals. The increase in the supply of assets for sale generated a greater poverty effect. The consequences were disastrous.

- As stated above, many banks went bankrupt. The Federal Reserve actually let some large public banks collapse (e.g., the Bank of New York, which today we would call a systemic bank), which added to the panic and to the runs in the local banks. Worse still, the Fed stood idly by while the banks went to the wall.

- Depositors began to withdraw their savings more quickly, as many of them believed that other depositors were about to do the same. Obviously, a large wave of bank runs ensued between 1930 and 1931. Bernanke’s journal article provided evidence of the significance of these bank runs during the Great Depression. The ramifications of this panic led to an outflow of deposits, and, as a consequence, credit rationing and the collapse of many banks.

- When panic and deflation set in, people believed they could avoid further losses by staying away from banks. Many families put their money in safes and under their mattresses. The result led to wealth being diverted to unproductive uses. Furthermore, the incentive was to hoard money and not to spend it. Indeed, this liquidity became very profitable because, as prices fell, more and more products could be bought with the same amount of money.

Bernanke’s article provides econometric evidence that it was the banking crisis caused by deflation, including the shift of household savings (from bank deposits to cash in the hands of the general public), that played a pivotal role in driving the economy into recession.

The 2008 Real Estate Crisis

There is no doubt that Bernanke is a prestigious economist renowned for his scientific work, such as this article highlighted by the Nobel committee, as well as other outstanding academic articles. However, Bernanke was also a policymaker and a central banker who had to take bold, tough decisions to tackle the real estate crisis of 2008.

Seventy-eight years after the Great Depression dawned in the United States, the so-called Great Recession reared its ugly head in 2007, also in the United States. The cause was the collapse of subprime mortgages, known as “junk mortgages.” The subprime real estate market had engendered a dangerous model based on systematic increases in housing prices. When those prices began to fall in 2006, mortgage defaults rose to an unprecedented level. The magnitude of the situation reached alarming proportions. This had a huge impact on banks dealing in mortgages, and later on the banking sector in general. Lending slowed, and, by the end of 2008, the banking crisis turned into a global economic crisis.

There were major similarities between the Great Recession and the Great Depression. Just swap the words “credit” and “stocks” for “real estate” and the description of the 1930s financial crisis could be used to explain that of 2008. The resemblance, in fact, was out there for all to see. In 2008, banks began to reject requests for loans that used real estate as collateral (in the 1930s, they refused loans secured by shares.) This meant that many people had to sell their homes to pay mortgages they could not afford in the Great Recession. With home prices plummeting, the “housing bubble” burst.

Fortunately, Bernanke – an expert in banking crises – was the chair of the Federal Reserve at the time. The monetary policy response to the crisis began in December 2008 and ended in 2010. From the beginning, the Fed Chairman chose to implement monetary easing to prevent a banking crisis. He lowered interest rates and cranked up the moneymaking machine, buying huge amounts of government bonds and mortgage assets to generate liquidity. This lowered mortgage interest rates in the U.S. housing market, making it easier to obtain loans. These unorthodox expansionary measures were called Quantitative Easing (QE1). They were stopped in March 2010.

However, in November 2010, given the “disappointingly slow pace” of the economy according to Bernanke, the Fed activated a second monetary expansion program, known as QE2, in which it acquired €600 billion in bonds. In September 2011, in the face of an incipient recovery, the Fed scaled back its approach, stopped buying bonds and began the return to normality. At the same time, in the so-called “Operation Twist,” it swapped $400 billion in short-term debt bonds for the same amount of long-term debt. This enabled it to reduce yields on US government debt, instead pushing investors into more profitable assets, such as corporations.

In general, Bernanke’s handling of the housing crisis received favorable comments from economists. However, some blame him for the current inflationary crisis caused by the pandemic and the Ukraine War. The expansionary policies, implemented during his tenure at the Fed, could be at the root of today’s inflation. Others think that the responsibility may lie with those who succeeded him, who failed to implement more restrictive monetary measures, i.e., to reduce the amount of money in circulation.

This is why there has not been widespread recognition for Bernanke. He does have his defenders. One of the world’s leading experts on monetary policy, Robert Lucas, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economic Science, has said in reference to the 2008 crisis that Bernanke did what had to be done and prevented a repetition of errors of yesterday and ended the liquidity crisis.

Could the Fed have done much more to avoid recession and boost recovery? Probably not. There is justice in the former Chairman of the Federal Reserve being awarded the Nobel Prize. But the world moves on quickly and we must address what is before us now. The key question now is whether there is a new Bernanke on the scene who will rescue us from the current inflation crisis caused by the invasion of Ukraine.

This article originally ran in Spanish in Nueva Revista.

© IE Insights.