Link copied

IE insights - IDEAS TO SHAPE THE FUTURE - Power

Shaping the Future of AI Governance

Thinking in the short- and long-term simultaneously will enable the creation of favorable AI governance systems.

The artificial intelligence boom may very well flatten out in reasonable time, but it will long continue to be relevant, particularly where it intersects with other technological advances. Roy Amara, former President of the Institute for the Future, famously said, “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” And it is this misperception of the impact of technological change over time, this dissociation between present and future – between the now, next, and new – that has implications in the current AI regulation debate.

Technologies, especially emerging and disruptive ones such as AI, bring about constant and rapid change with profound consequences on prosperity, power, politics, peace and security, and how we understand “humanity.” To navigate the growing – sometimes silent – change to which these technologies expose us, and to narrow the aforementioned dissociation gap, it can be useful to position ourselves as futurists and cultivate a foresight mind with a panoptic vision of trends and futures.

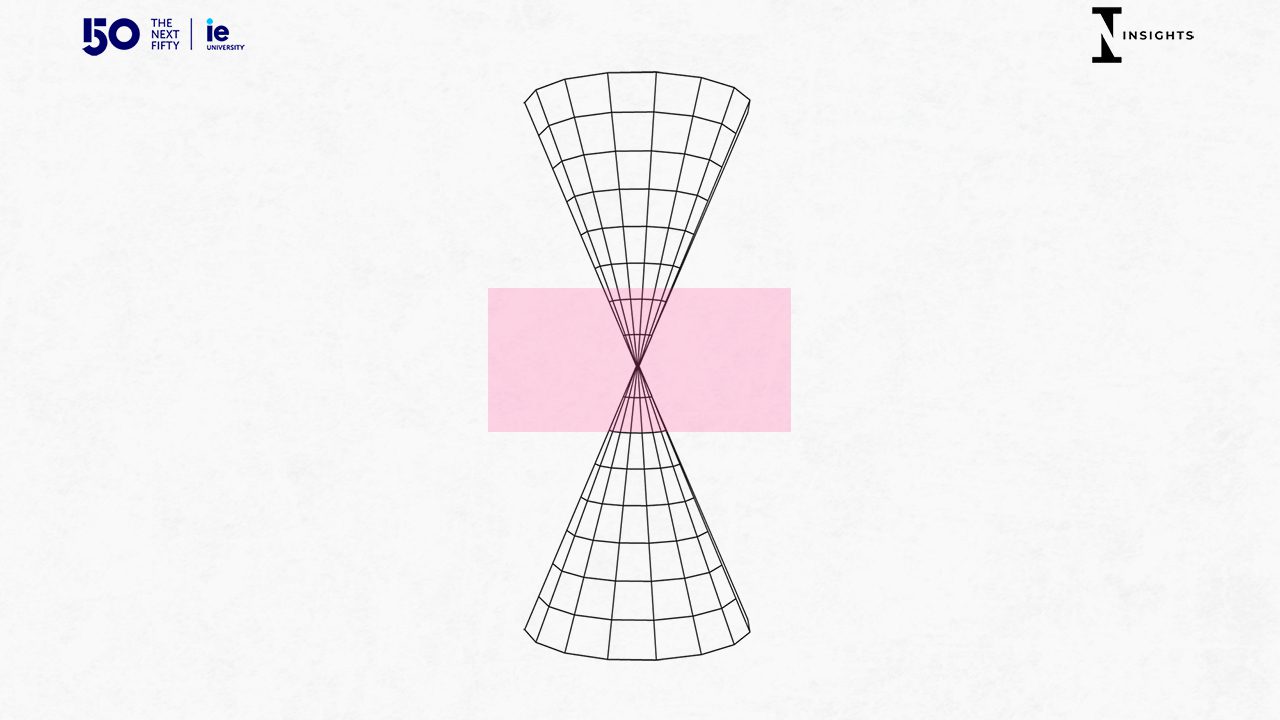

Futurists think differently about time. As Amy Webb explains, for any given uncertainty about the future, be it a risk or an opportunity, futurists tend to think in the short- and long-term simultaneously. They do not use time lines; they use time cones, based on the concept of light cones proposed by Hermann Minkowski (who also happened to be a professor of Einstein.) The edge of the time cone (also known as futures cone) signals the present and highly probable events for which there is already data. The open ends of the cone take us into more distant futures for which there is no data or evidence, so uncertainty is the rule. They project possible, probable, plausible, and preferable futures, as illustrated by Trevor Hancock and Clement Bezold.

The debate about technological governance is very lively. A dichotomy may help explain the discussion. There is widespread situational awareness (and evidence) of the potential of AI as an agent of progress and social good. At the same time, there is broad caution about the future challenges posed by an increasingly closed AI, with less – or detached from – human interaction, which may pose existential risks for the future of humankind. Autonomous agents (AutoGPT) paving the way to artificial general intelligence come to mind.

AI governance raises a double dilemma. One is epistemological: does it make sense to regulate in a written-in-stone manner the permanent change that this technology entails? The other is a weighting dilemma: what should be regulated? AI applications, sectors, risks? And what are the values, principles, and interests to be protected? Is the canonical trade-off between innovation and security founded and sustained? Weightings are never zero-sum.

I align myself with those who prefer to dismantle the myth that governance stifles innovation. Governance is per se innovation. Regulation should focus on the three key elements of AI: infrastructure, algorithms, and data.

The best AI governance systems will be those that are capable of monitoring the entire lifecycle of the technology, the foreseeable and the unseen, ex ante and ex post, from its ideation phase to its implementation and peak, and the effects it generates, with a particular focus on unintended consequences and existential risks, and adapting quickly and responding to these unwanted effects.

Such governance models should update these risks in a transparent, multistakeholder, and expert-driven manner, according to Andrea Renda, Senior Research Fellow and Head of the CEPS Unit on Global Governance, Regulation, Innovation and the Digital Economy. They will be core elements of a new AI geopolitics currently being defined around multistakeholder hubs. AI literacy will thus be key.

The general trend shows a significant level of agency on the part of international organizations and G-summits in the field of AI regulation – alongside the progressive positioning of corporations through the adoption of codes of conduct, principles, and guidelines that nurture this nascent, congested, and fragmented AI governance ecosystem.

The proliferation of regulatory instruments on AI governance is a sign of our time. We can expect a process of extensive cross-fertilization between these principles and rules of hard and soft law. In the future, what may very well emerge is a self-contained regime of international law for the effective global governance of AI, consistent with the principles of technological humanism. The Global AI Agency may become a reality, though it is not poised to take shape immediately.

Our present day includes great power competition, breakdown of value chains, and signals of decoupling – it does not allow us to be optimistic. But let’s think like futurists – and with hope – about the next 50 years, that this is where AI governance might be heading.

© IE Insights.