How the Economy Rhymes with the Past

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but many times it rhymes.” Professor Gonzalo Garland explains the similarities and differences between the current inflationary challenges facing the global economy and those of the 1970s and ’80s.

© IE Insights.

Transcription

Not only in economics but in general, there’s always been this discussion on whether history repeats itself or doesn’t. And I think the general agreement is that history does not repeat itself, but many times it rhymes. So even though just a couple of years ago when we were just going out of the pandemic, people were relatively optimistic, before the start of the war. People were comparing the times with the Roaring ‘20s of the previous century,.

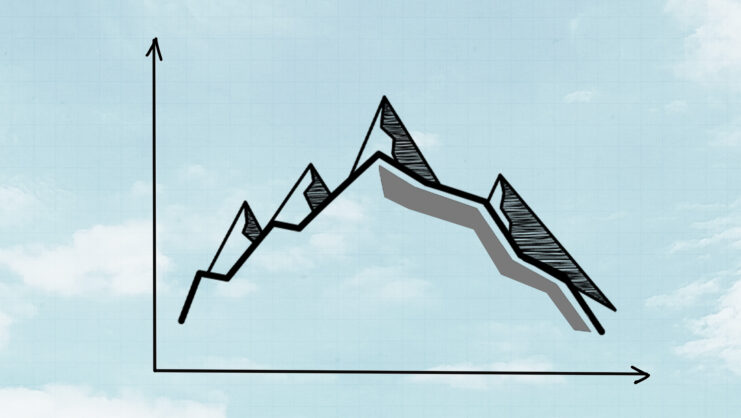

It’s a very optimistic time, but I think this comparison really was over once the war started and Russia invaded Ukraine. And there we started seeing inflation going up. And then the situation right now, I would see , and most people would agree, would resemble much more the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s rather than the Roaring ‘20s of the previous century Clearly, in the 1970s, what happened was there was a supply-side shock, and that is the oil shocks of the 1970s. There were two. The first one in 1973, the second one around 1978-79 that increased oil costs significantly and that increased inflation worldwide.

Well, that led us to what was called stagflation: stagnation together with inflation. And there are similarities, if we think about it with the situation now, probably the most important similarity, I would argue, would be the one at the beginning of the ‘80s, at the beginning of the ’80s in particular in the United States, when inflation was getting out of control, there was a very, very restrictive monetary policy. Basically, it’s Paul Volcker, very famous for increasing interest rates dramatically rapidly, and therefore forcing the economy to a very sudden stop. In fact, interest rates in the United States, for example, went all the way up to approximately 20%, which was huge and that produced a worldwide recession. And the unemployment in the United States went up to almost 11%.

There are similarities, again, with the fact that there’s a very strong increase in interest rates that we have seen in most central banks in the world, there are very few exceptions to that. Despite these similarities, there are clearly very important differences, too. So the first one would be the timing. In the 1970s, the timing of the response from the point of view of economic policy, in particular monetary policy was lower, in fact, and that was to a large extent because the theoretical background that economists was about, if you fell into recession, you had to apply expansionary fiscal policy.

So therefore you had to try to, in a way, pump more money into the economy. But that just fueled inflation even further. So that created this wage-price spiral. That was what was very dangerous because what happened is inflation went up and therefore, of course, workers wanted their wages to go up and therefore they went through strikes or the union negotiated quite strongly and therefore the wages started going up.

But of course, higher wages also create a feedback effect by which inflation continues to go up. So that was the main problem. The main problem during the ‘70s is that basically that price spiral became out of control. The most extended way of thinking about the crisis these days is precisely because we learn from the crisis in the 1970s, in the 1980s. The decision right now has been monetary policy has to be restrictive immediately, as soon as possible, so we don’t get out of control. But there are others, similar to what happened during the early 1980s, when you apply a very restrictive monetary policy and interest rates start going up very dramatically, of course, financial cost goes up.

So what happens: if you have external debt, for example, if you’re a developing country that has a very large external debt in US dollars, then what happens is interest rates go up, the US dollar becomes stronger many times during this crisis because very high interest rates in the United States attract a lot of capital to the United States, which strengthens the US dollar. And therefore, what happened at that time was that we saw a huge worldwide crisis, debt crisis in 1982. We saw first Mexico, Latin America, particularly in Latin America, but not only, and they went on default. It started with Mexico and practically all of Latin America went on deault. This time there are some differences, but are some similarities.

On the one hand, again, interest rates go up. We haven’t seen yet crisis in Latin America, but we’re seeing crisis in other parts of the world. So we’re having serious issues with some African and Asian countries, particularly Pakistan or Sri Lanka or Zambia or Ghana. These countries find themselves with very huge debts they have incurred in recent years. Interest rates go up, the dollar becomes strong. They find themselves without being capable of repaying that. However, overall, what I would say is I think this time, instead of spending so much time with inflation and inflation going up in the spiral of inflation and then a very dramatic and drastic intervention of monetary policies, I think hopefully because we learned from the past, the timing is slower once we start seeing inflation getting out of control.

There’s a very clear intervention from the central banks and hopefully that will mean that the extent of the crisis and the extent of the adjustment would be much smaller in that sense. If we are able worldwide to control inflation faster, then we’ll probably be much sooner in a situation where interest rates can go down again and therefore promote growth again, probably after a mild or relatively mild recession rather than the huge unemployment levels that we saw in the early 1980s and the huge inflation that we saw out of control right before that very, very strict monetary policy.