IE School of Architecture and Design’s professors explore sustainable strategies and the impact of the virtual realm

Déborah López and Hadin Charbel discuss their experimental award-winning work and research.

Pareid is an interdisciplinary design and research studio based in London and Spain, led by Déborah López and Hadin Charbel, who also teach in the Bachelor in Design and Dual Degree in Business Administration and Design programs at IE University. Winners of the latest Arquia/Innova Award for their emerging architecture practices, they continue to push boundaries in design and academia, drawing from diverse fields and contexts to explore climate, ecology, human perception, and machine sentience. We spoke with them about their achievements, challenges, and their role as professors at IE School of Architecture and Design.

Your project Everywhere & Nowhere won the latest edition of the Arquia/Innova Award. What inspired it, and how does it align with your studio’s focus on climate, ecology, and alternative realities?

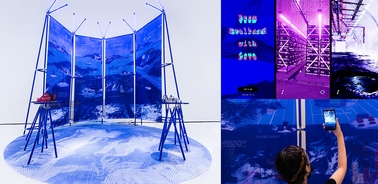

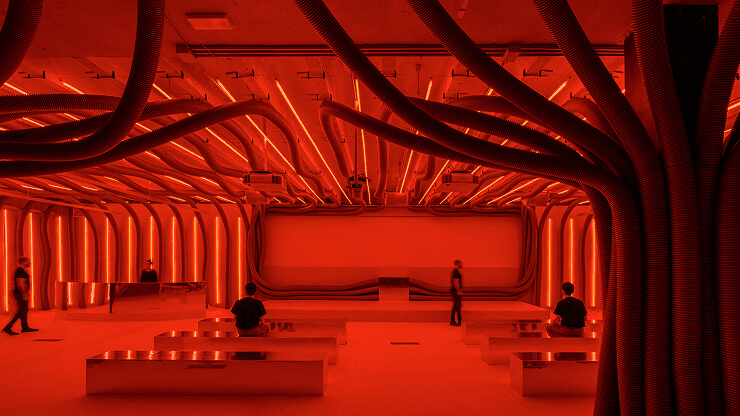

We were asked to design a temporary immersive space for the Urvanity Art Fair, serving both as a venue for public talks and an informal gathering spot for visitors. Three key factors shaped the project: location, duration, and program. Located inside the Madrid Architects Association (COAM) building, the structure had to be self-supporting and non-invasive. Seeking a novel approach, we used clamps to suspend irrigation tubes from the building’s existing beams, allowing for easy disassembly without leaving a trace.

Everywhere & Nowhere by Pareid. Photo: Javier de Paz García

Our choice of material also stemmed from an interest in the hidden systems shaping our daily lives. The installation highlighted the interconnectedness of everything, aligning with the space’s role in broadcasting talks. This approach reflects our ongoing exploration of climate and ecology, while also challenging traditional aesthetics associated with sustainability.You often bridge architecture with topics like cli-migration, machine sentience, and alternative futures, as seen in From Svalbard with Love (illustrated on the cover of this article). How do you approach these interdisciplinary themes while maintaining a clear architectural narrative?

We are trained as architects, and that foundation will always be part of our approach. However, what our educational background taught us, and what we also try to teach is that architecture is more than just building – it is multi-faceted, having impacts and being impacted by a myriad of forces, whether they be political, environmental, or economical. Viewing it this way from the outset, and researching along those fronts, naturally facilitates how narratives can emerge.

You will participate in the `The Digital Frontier: Virtual Spaces and Their Place in Our World´ panel at Madrid Design Festival 2025 organized by our school. What will you be presenting, and how does it reflect your practice’s ethos?

Some of our recent work has begun shifting from the speculative to the real, particularly in exploring participatory design and virtual heritage preservation—both of which we look forward to discussing on the day. These projects reflect our practice’s ethos, as they are highly context-specific, with the chosen technologies responding to the unique demands of each research question.

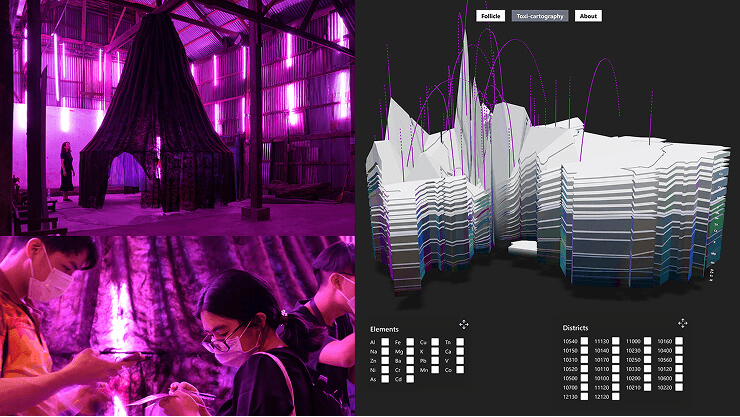

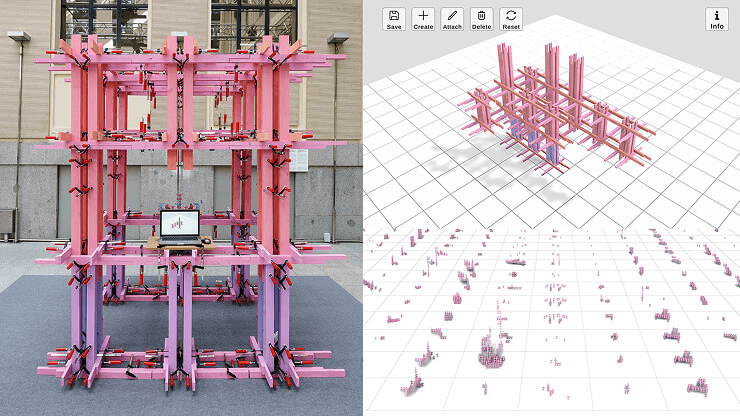

Participatory design has been a key interest for us, both in our teaching and practice. Our first major exploration in this area was TOCA (Tool Operated Choreographed Architecture), a collaborative project developed during our master’s studies. It investigated how to orchestrate human and machine collaboration in fabricating a pavilion. Since then, participatory design has taken various forms in our work. For instance, in Follicle, the public contributed locks of hair, which were analyzed for heavy metals to map urban toxicity through its inhabitants. More recently, we have been involving multiple stakeholders in the decision-making process of spatial design, often through game-based frameworks—whether in the form of video games or interactive negotiation systems.

Follicle pavilion. Photos©Pareid

Our work in virtual heritage preservation stems from real-world constraints—many valuable heritage sites face threats from environmental, economic, and social pressures, making proper preservation difficult. Our use of digital technologies serves not only to document and protect these sites before they disappear but also to actively engage the public through interactive experiences. The ultimate hope is that this collective sense of care produces a positive impact, allowing preservation efforts to move from the virtual back into the physical realm.

Do end users, or customers always know what they need?

Yes and no—though most often, partly. What we mean is that while there is usually a general understanding of what is needed, there are multiple ways to fulfill or materialize that need. It is through design and dialogue that a direction is ultimately determined. However, just as design is iterative, so too are needs—they can evolve, expand, contract, or shift as the project develops. Take Follicle, for example: the project took place in Bangkok without a client, as it was part of a design festival and simply an idea we pitched. Coincidentally, it aligned with a moment when pollution levels in the city had reached critical levels, forcing the closure of schools and public buildings. The public, without being explicitly asked, was eager to take action. Their willingness to participate in a collective project that directly addressed urban pollution suggests that, in a way, this was something they both wanted and needed.

As both practitioners and educators, how do you balance the demands of running Pareid with your teaching roles? How do these roles influence and complement one another?

Balancing may not be the most accurate word, but we are essentially equally interested in practicing as we are in teaching, finding both territories enriching in their own ways, and believe that keeping the two in a bi-directional dialogue is the best way to keep them both fresh and innovative.

As adjunct faculty of IE School of Architecture and Design, what do you value most about teaching here? How does the academic environment at IE align with or enhance the work you do in practice?

There is a keen curiosity by students to figure out what design is all about, and this in many ways is the best thing one can ask for. There is a relentlessness in the work, which is admittedly challenging as it asks for research, new skills, and design to happen almost all in parallel. But, what is undoubtedly rewarding is when students make it through to the other side, and when it feels like the entirety of the semester was collectively working and learning towards a common goal. On a parallel front, there is also a trust in and among the faculty that provides the space for autonomy and creativity in pedagogy, while being collegiate and critical, which is also key in maintaining both the level and the spirit in the school.

As emerging voices in the architecture world, you have already gained significant recognition. What advice would you give to young architects looking to navigate experimental practices while making them economically viable?

Take as many different opportunities and risks as you can early on. Try to learn something new from each project. Don’t be afraid to ask others who are more experienced or going through the same process as you questions – it's a profession that works best through different forms of collaboration.