26/11/2024

It's easy being on top when everything's going well. Leadership in crisis? That's a whole other beast.

Crisis is inevitable. The mark of a true leader is being able to react when it matters. We’ve arranged a list of key strategies for high-stakes decision making—and we’ve used situations from the multiverse of fiction and non-fiction. Ranging from crisis management in Wallstreet to quelling a riot with a soft drink, we’re going to ensure the next time you’ve got to make a big decision, you have great examples to follow… or avoid.

Don Draper in Mad Men: recontextualizing the crisis

Lucky Strike decide to leave “SCDP” for another ad agency. The company of our protagonist-creative-director Don Draper, SCDP simply can’t survive without Lucky Strike in its portfolio. Soon enough, other clients jump ship and possible leads avoid SCDP like the plague. It’s a high-profile business breakup with apocalyptic impacts for our beloved cast of characters.

Salvation lies in a turn of phrase oft repeated: “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation.” Draper publishes an open letter in The New York Times. It’s pure spin; instead of a rejection from the client, Draper frames the breakup as his own ethical decision. Controversial, but his recontextualization of the crisis saves the day.

“Regardless of how you feel inside, always try to look like a winner. Even if you are behind, a sustained look of control and confidence can give you a mental edge that results in victory,” Arthur Ashe

It’s not all fiction, either. There was a real ad exec who authored a similar letter as published in the Times’ archive. However, the ex-chairman of McCann-Erickson were far more virtuous. A reformed chain-smoker, Emerson Foote did ultimately leave the ad industry to avoid promoting cigarette addiction.

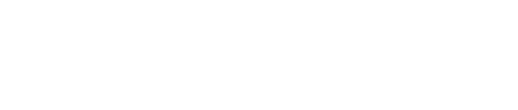

Michael Burry: preparing for leadership in crisis

Michael Burry came out the right side of the biggest financial crisis of this century. As popularized in “The Big Short”, Burry famously bet against the housing market before its collapse in 2007-2008. His insights on subprime mortgage loans made to borrowers with poor credit histories meant that his fund, Scion Capital, won its investors many millions in profits. But it wasn’t so simple.

“Back in 2005 and 2006,” Burry said on his famous episode of leadership in crisis. “I argued as forcefully as I could, in letters to clients of my investment firm, Scion Capital, that the mortgage market would melt down in the second half of 2007, causing substantial damage to the economy.” Despite skepticism, Burry’s dogged belief in the data paid off.

The moral? Anticipate crises with healthy cynicism and fight like hell to keep disaster at bay.

“What you want to watch are the lenders, not the borrowers,” Burry noted on the situation. “The borrowers will always be willing to take a great deal for themselves. It’s up to the lenders to show restraint, and when they lose it, watch out.”

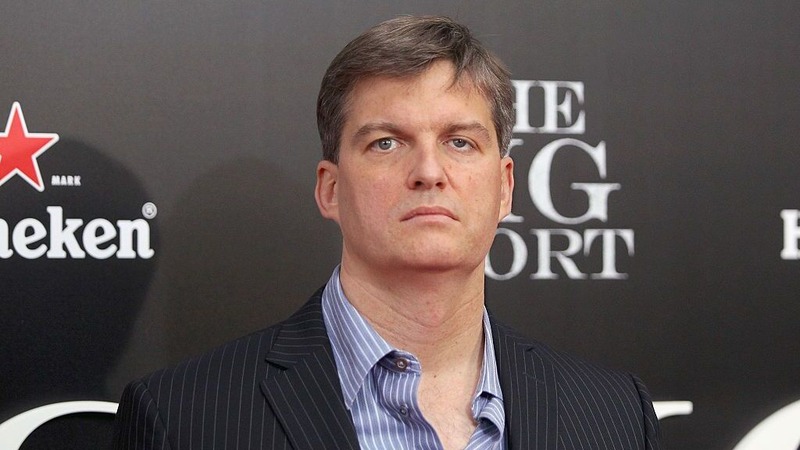

Glengarry Glen Ross: shifting the blame

In David Mamet’s play-turned-screenplay shows a quartet of real estate salesmen in crisis—and it all comes from pressure by management. “First prize [for making sales],” Alec Baldwin’s Blake explains, “is a Cadillac Eldorado. Anybody wanna see second prize? Second prize’s is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired.”

Desperation turns the businessmen haywire as they’re struggle to come out on top—two actually selling leads to a competitor. Regardless of the pressure from above, the managers in “Glengarry Glen Ross” handle leadership in crisis by creating a culture of betrayal.

“The good news is—you’re fired. The bad news is you’ve got, all you got, just one week to regain your jobs, starting tonight.”

The moral is clear: competition is inevitable in business, but pitting employees against one another is a miserable, costly, and often ineffective form of motivation.

Kendall Jenner: knowing the value of an ice-cold beverage

Picture this: a line of law enforcement gathers before protestors. One side wants love, the other wants order. Now imagine you’re Kendall Jenner—blonde wig donned, lips smokey red. But something’s missing. Called to action by an ethnically ambiguous cellist, you tear away from an important photoshoot and run to the protest’s frontier. Crisis is afoot. The solution? A can of ice-cold Pepsi.

Of course, I’m joking—Pepsi’s ill-advised campaign drew off the real-world crises of black anti-police-violence protests to sell a sweet beverage. Its public reception was far from positive. Remember—if things are tense, don’t poke the dragon.

Pepsi in turn handled this PR crisis with a swift apology: “Pepsi was trying to project a global message of unity, peace and understanding. Clearly we missed the mark and we apologize. We did not intend to make light of any serious issue.”

Navigating leadership in crisis? Sometimes it’s best to hold your hands up and say “we apologize”.

Benjamin is the editor of Uncover IE. His writing is featured in the LAMDA Verse and Prose Anthology Vol. 19, The Primer and Moonflake Press. Benjamin provided translation for “FalseStuff: La Muerte de las Musas”, winner of Best Theatre Show at the Max Awards 2024.

Benjamin was shortlisted for the Bristol Old Vic Open Sessions 2016 and the Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize 2023.