New technologies will transform what is required from tomorrow’s designers and architects. The pace of change in areas such as artificial intelligence (AI) and new synthetic materials makes rethinking traditional design imperative. This report will explain the challenge facing the next generation of designers and architects: how to maximize the use of new tools to solve issues such as sustainability and increased automation.

- HOW ROBOTS ARE REWRITING THE RULES

- ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, FROM SCIENCE FICTION TO FACT

- TECHNOLOGY TO MEET HUMAN NEEDS

- URBANIZATION AND MEGACITIES

- SMART SUSTAINABILITY

- NATURE: IS THIS THE FUTURE OF DESIGN?

- IS TECHNOLOGY A SOLUTION OR A TOOL?

- ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN TAKEAWAYS

How robots are rewriting the rules

Before designers and architects pour forth their visions for a better world, first they need to know what technologies are reshaping our future. But, at the same time, they need to remember that basic human requirements do not necessarily alter that much. “The fundamental needs and desires of people are quite static; what changes is how they are expressed and perceived dependent on the changing technological and environmental context,” says Josef Hargrave, global foresight manager at Arup, an international design and engineering consultancy.

AI is already a $15 billion industry, expected to reach $38.6 billion by 2025 and it is growing rapidly. Recent victories by AI software over top poker players show that machines have developed the ability to learn from imperfect information, just like people do.

Today the multinational ISS Facilities is using IBM’s Watson to optimize its operations, and Google’s Deep Mind has reduced energy consumption in its data center by 40%. “Today it’s about application, correlating data sets,” says Owen King, a consultant at Unwork. “And with AI there is a real difference between general AI and case specific.” In the short term, he points out, “Large parts of AI and other new technologies will push old industries out of the way — like building management systems (BMS).

Amanda Clack, head of infrastructure at Ernst & Young and global president of RICS agrees, saying: “Disruption is a question of when, not if.” Robots have transformed manufacturing over the last few decades, fundamentally impacting working patterns. Clack is in favor of robots taking out parts of repetitive work in design and architecture, such as processing applications in planning.

In 2017, 16 million consumer robots are expected to be sold. They are now commonplace in Japan and one in 10 US households is predicted to have a robot housekeeper by 2020.

Drones also have the potential to create widespread change in logistics and how people operate. Amazon has not only begun trialing drone delivery to homes, it has patented an aerial delivery platform from which drones can supply consumers. And the Canadian engineer and innovator Charles Bombardier has already created a concept for a Drone Tower, which shows how architects of the future might need to redesign buildings for drone landings.—

Technology to meet human needs

Technology does not exist in isolation. “Disruption is about much more than technology,” says Simon Giles, Global Cities Digital Lead for Accenture. While the pace of technological change is accelerating, there are other trends that are going to have a direct impact on the way in which we live. And given that, as humans, we must design and build places where we can live, work and play, those factors will affect how we design and build. “Understanding future needs is complex but there is a little guidance on how culture changes — there are interconnected sets of factors that influence that,” notes Arup’s Hargrave.

From climate change and resource scarcity to the growing global middle class and increased polarization of society, the challenges are many. What matters is that we start to think about how these different things interact, and how these pressures and difficulties might identify what needs to change in the future of both architecture and design.

“Disruption is about much more than technology”Simon Giles, Accenture

That is something that is already happening. A team from the IKEA Foundation (working with UNHCR) recently won the Beazley design of the year award 2016 from London’s Design Museum for its solar— powered Better Shelter. An outstanding contribution to the issue of global population displacement, it is a robust 17.5-square-meter shelter that fits inside two boxes and can be assembled by four people in just four hours. With UNHCR estimating that over 2.5 million people have lived in refugee camps for over the past five years, it is a practical design that can make a real difference.

Planned obsolescence in devices has caused its own challenges. It is hard to miss the news of e-waste pollution, especially in the developing world. The people behind the Fairphone 2 took an alternative approach to the complexity of the modern smartphone, designing a handset with elements that users can fix and replace with everyday household tools, such as screwdrivers.

“If there’s going to be a massive global crisis, architects and designers will be part of the solution”David Goodman, Director of IEU’s Bachelor in Architecture

“We are at a transitional point where certain ideas are starting to be questioned,” explains David Goodman, the Director of IEU’s Bachelor in Architecture. “Stylistically, we are in an era in which we may be about to have a huge shift toward functionalism linked to issues of sustainability and climate change. If there’s going to be a massive global crisis, then architects and designers will be part of the solution.”—

_Seed Cathedral, the UK Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, combined modern materials and lighting technology with biological forms to create a unique, intimate and human experience. It was visited by eight million people._

Smart sustainability

The need for sustainability and resilience is becoming ever more important in designing products, buildings and cities. As Jim Heid of Urban Green says, “the need is to move from creating individual solutions to participating in the design of the larger system.” Whether thinking about the circular economy, the need to recycle, use clean energy or create green spaces, it is about sustainability within a system, not of any individual element.

Where we live is as important as how we live. As urban centers are home to the majority of the world’s population, sustainability improvements within cities — from energy efficiency to water management and clean air — can only improve economic and environmental impacts.

For example, buildings use about 40% of the world’s energy, with residential and commercial structures alone using 60% of the globe’s electricity.

Traditionally, city systems, from energy to transport and waste disposal, have operated independently of each other. Smart systems could enable the integration of these infrastructures to share data and resources, save energy and serve more people.—

Urbanization and megacities

The role of the city cannot be underestimated. According to data from the United Nations, in 2016 an estimated 54.5% of the world’s population lived in urban settlements. By 2030, urban areas are projected to house 60% of people globally, and one in every three people will live in cities with at least half a million inhabitants. The world already has 31 megacities (with over 10 million inhabitants) — six in China alone — while another 10 cities are projected to become megacities between 2016 and 2030. As increasing numbers of people live in cities, we must find new ways to create places for living, working and playing, while maximizing the utilization of space.

- 60of the world’s population will be urban in 2030

- 41megacities will be built with more than 10 million inhabitants

Nature: is this the future of design?

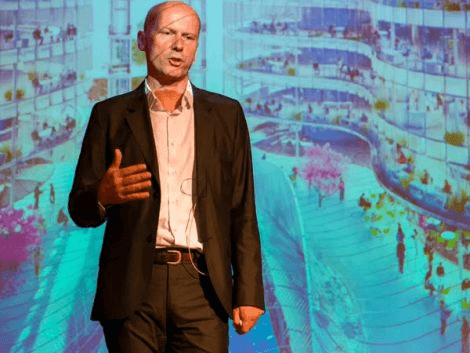

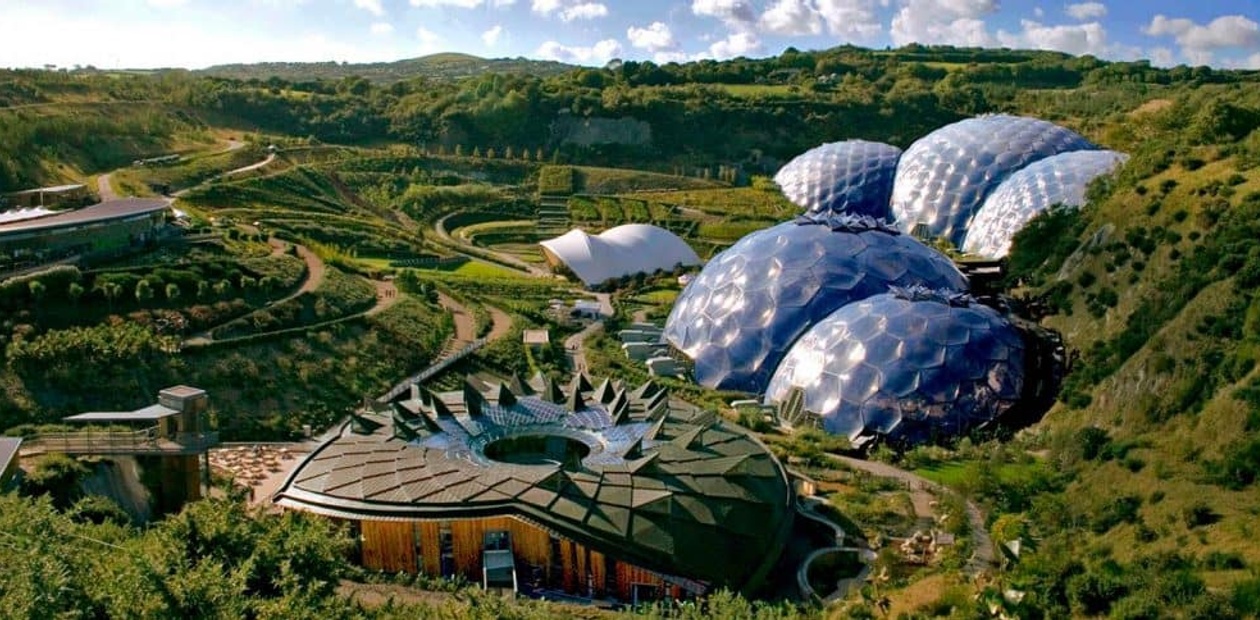

Michael Pawlyn is a leading advocate of biomimicry — the study of natural structures and processes in order to help solve man-made problems. Its goal is to create products, processes, and policies that are well adapted to life on Earth over the long term. The premise is that over millions of years nature has already solved many of the problems we are grappling with, such as the way a leaf obtains energy or the self-cooling mounds of termites. Pawlyn was part of the principal team of architects that conceived and designed The Eden Project in Cornwall, England, and in 2007 he established the architecture firm Exploration to focus on developing new, sustainable architectural environments.

What major shifts, if any, have taken place in architecture and design in the last couple of decades?

Unfortunately, there has been relatively little progress in terms of bridging the divide between, on the one hand, urbanism as a predominantly culturally led design discipline and, on the other hand, ecological thinking as an approach that attempts to design for a positive future within realistic physical limits. There has been a surge of interest in what William Myers broadly defines as ‘BioDesign.’ But within that there are very variable levels of rigor in applying lessons from biology.

What does biomimicry have to offer in architecture and design?

There has been a fragmentation of the sustainability debate into initiatives such as ‘resilient cities,’ ‘100% renewable cities’ and, more comprehensively in terms of vision, the idea of a circular economy. This has the potential to create confusion, particularly for those people who are on the edge of the debate. Biomimicry, particularly the aspect concerned with applying ecosystem models, has the potential to unify these initiatives and lead to solutions that are fully cyclical, resilient, diverse, regenerative and run entirely on solar energy. Biomimicry also has the potential to deliver radical increases in resource efficiency by applying proven solutions to innovative structures, materials and ways of lighting, heating, cooling and generating energy for buildings.

What do you see as the key role of architects and designers in society?

I see architects and designers as having an important role in shaping a positive future and developing solutions that offer improved quality of life. It is hard to beat Buckminster Fuller’s mission statement which was: “To make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone.”

Is the pace of change accelerating and, if so, is this a threat or opportunity for new designers and architects?

The pace of change is accelerating in other fields such as renewable energy, battery storage, and the Internet of Things — and these will have some effect on architecture and design. There is some cause for concern that the increasing use of algorithmic design tools will take away some of the tasks normally done by designers, but it could be argued that it will help them address some of the technical aspects of optimization and release them to focus on other important aspects of design, such as the more cultural sides of architecture.

What skills/outlook do you think the next generation of architects and designers will need?

Susannah Hagan makes the case very persuasively in her book Ecological Urbanism that architects and designers need to be both environmentally literate and culturally literate. Currently, architects and designers tend to be one or the other and rarely both. Hagan makes an incisive and pertinent criticism when she says: “The longer architects and architecture schools ignore the politics, economics and science of meaningful change in the built environment, the closer they will come to being what they profess to despise: stylists to the rich and famous. If the worthy can’t design, and designers are unequipped, architecture is finished as a profession with any influence on the improved future of cities.” I remain positive about the prospects of architects and designers achieving this unity.—

“The longer architects and architecture schools ignore the politics, economics and science of meaningful change in the built environment, the closer they will come to being what they profess to despise: stylists to the rich and famous”Susannah Hagan, Director of Research into Environment + Design

The Eden Project built ‘biomes’ to house tropical and subtropical environments on the site of a former clay mine.

Is technology a solution or a tool?

For many, technology is the solution to any challenge. As software becomes increasingly complex, it is able to manage and model new shapes, sizes and structures of buildings. But as David Goodman, director of IEU’s Bachelor in Architecture points out, “The tools of technology have gotten ahead of us. When we were students, we would draw to figure out what was going on, make a physical model. Often design would happen during those moments of reflection. There is a degree of abstraction in that process, and we filled in what was needed with our minds. Students can now create things so quickly that we need to explain that they need slowness. We must teach them to use tools effectively and not squander their power.”

After all, Goodman adds: “If you have a 3D printer, what’s the point of creating something that could easily be made in cardboard? Why use a laser cutter to cut out squares? Push the tools to see what you can create.”

Tom Dollard, head of sustainable design at Pollard Thomas Edwards agrees that a growing reliance on technology to solve problems quickly has prevented many designers and architects from engaging with problems. “Twenty years ago we had a better grasp of technical issues and the process side has suffered for this. The temptation is to throw technology at a problem and not think about the design. Historically there would have been a conversation about materials, lighting, heat – inherently architectural problems.”

“Students can now create things so quickly that we need to explain that they need slowness”

David Goodman Director of IEU’s Bachelor in Architecture

Data has a critical role to play in the future of design but should be used simply as one more factor in design. The temptation is to make a building the physical representation of data but what is more interesting, according to Goodman, is flexibility and the ability to respond. Giles agrees: “In too many cases, technology is a solution is search of a problem.” As a tool, technology can have a significant impact – as when NBBJ created a model to assess the impact of different building shapes on worker interaction before developing Samsung’s Palo Alto R&D headquarters. “The future for architects, and designers is that they need to embrace new technologies and pick up the in-between spaces. The architect is the generalist, the conductor, the overall center of the vision,” explains Unwork’s Owen King.

Goodman says that architects have to ask themselves not what, but why. “Architecture is a field in transition; the big and bold modern statements of the past century are increasingly undermined by doubts borne of the financial crisis period of the past decade and greater awareness of the need for sustainable structures and use of energy and materials.”

New technologies are creating new ecosystems that are both redefining and straddling industries. Today’s students of design and architecture must look at the world with new eyes. It is arguable that they should learn new skills in data analytics but, as Amanda Clack says, there is not a professional out there today who does not work with data. “The world needs trusted and skilled professionals, considering economic, environmental and social outcomes.”—

ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN TAKEAWAYS

NEW TECHNOLOGIES ARE FUNDAMENTALLY RESHAPING THE WAY IN WHICH WE LIVE OUR LIVES

BEWARE THE TEMPTATION TO THROW TECHNOLOGY AT A PROBLEM AND NOT THINK ABOUT THE DESIGN

ASK NOT WHAT BUT WHY

THE WORLD NEEDS TRUSTED AND SKILLED PROFESSIONALS, CONSIDERING ECONOMIC, ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL OUTCOMES

Further reading

- 3D Printing explained by Christopher Barnatt

- Defining the Internet of Things

- Parametric Architecture

- Biomimicry defined

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Some information has been compiled by third party sources that we consider to be reliable. However, we do not guarantee and are not responsible for the accuracy of such. The views of third parties set out in this publication are not necessarily the views of IE University and they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.