Leaning into irrationality

How our understanding of human nature is shifting economics.

For many years, economists have understood that humans make economic decisions based on rationality, self-interest and profit maximization. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest,” wrote Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations. John Stuart Mill, another hugely important political economist, backed that vision. “[Political economy] is concerned with [man] solely as a being who desires to possess wealth, and who is capable of judging the comparative efficacy of means for obtaining that end,” wrote Mills in the 19th century.

Such notions of a rational economic actor whose economic life entails maximizing utility as a consumer and profit as a producer penetrated mainstream economics for most of its history. Today, however, that framework for understanding economic decision making has been put in serious doubt.

“You cannot be a good economist these days without understanding the irrationalities that affect how people make economic decisions, and all of the ways that psychology plays into economics,” said Lee Newman, Dean of the IE School of Human Sciences and Technology.

Optimism bias- people, on average, predicted a kitchen renovation will cost $18,658 but the real average ended up being $38,769.

By the year 2002, behavioral economics really hit the mainstream. Daniel Kahneman, who helped pioneer the fusion of psychology and economics, won the Nobel Prize in Economics (shared with Vernon L. Smith). One of Kahneman’s fundamental arguments is that humans make decisions based on rapid, automatic urges as well as thoughtful, deliberated choices.

With data coming out of psychological experiments, it became apparent that each individual has a range of biases, illusions and instincts that fuel their economic choices.

For example, Kahneman suggests that unwarranted optimism is one of the most prevalent biases, with people tending to overestimate benefits and underestimate costs. He points to a 2002 study which suggests that Americans remodeling their kitchens expected the job to cost $18,658 on average, but they ended up paying $38,769. This is one of many psychological insights that are relevant to understanding how people interact with the economy – what they buy, what career they choose, or how they invest their money.

A nudge is a concept in behavioral economics that proposes techniques like positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as a way to tap into the unconsciousness and influence economic actions.

“A nudge… is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives,” wrote Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in a 2008 book that brought the term to prominence. “Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.”

How to make people pay taxes with a nudge

The Behavioural Insights Team - established in 2010 and known unofficially as the “nudge unit” – was set up to apply the economic nudge theory to improve UK government services and efficiency. One of their experiments found that people were more likely to pay overdue taxes if just one sentence was added to the letter requesting payment, such as: “nine out of 10 people in Exeter pay their taxes on time; this puts you in a minority of 3,000 people.”

By adding that sentence, adjusted to the locality, people were five percentage points more likely to pay their taxes. This drew on the psychological knowledge that social norms are an important factor in economic decision-making.

“Framing people’s actions as minority behavior triggers a subconscious feeling of being an outsider, which creates a fear that you don’t belong anymore,” said Ivo Vlaev, a co-author of the study. “A motivation emerges to affiliate with the majority group, which in this case, is people who pay their taxes.”

“You cannot be a good economist these days without understanding the irrationalities that affect how people make economic decisions”Lee Newman, Dean, IE School of Human Sciences and Technology

The attention economy: Navigating the economics of social media

Digital technology that enables precise data to be collected about how an individual interacts with a product has given rise to a new economic model – one that runs on time. Facebook, for example, is a free platform that allows its two billion users to connect, share images and ideas. The company’s 2018 profit reached $46.5 billion.

Instead of other similarly massive enterprises that extract resources or manufacture products, the main resource Facebook sells is its users’ time. “Attention is a resource – a person only has so much of it,” wrote author Matthew Crawford in The New York Times.

Vast amounts of data are being collected on our every online move, and time spent per page and engagement with content are two key metrics that motivate advertisers. So, social media companies tap into psychology and develop their platforms so users will go online as often as possible and stay engaged for as long as possible.

From push notifications to algorithms that place what is considered to be the most engaging content on the top of the feed, each feature has been carefully designed to grab attention.

Addicted? According to a 2019 study by We are Social and Hootsuite, the average person spends 6 hours and 42 minutes online each day. That’s more than 100 days spent online each year, and companies of all kinds are fighting for a share of that precious time. Photo: Hugh Han

“Attention is a resource – a person only has so much of it”Matthew Crawford, American writer

As attention shifts to social media platforms, advertisers can also get a glimpse into the personal lives of their potential clients like never before, through looking at their public profiles, social networks and other metrics. As companies vie to appeal to the customers they have targeted and worked to understand, they have also found new ways to grab attention that goes beyond the basic digital advertisement.

Instagram and the age of influence

According to the Mediakix marketing agency, sponsors paid social media influencers on Instagram alone around $1 billion in 2017. Influencers are people with a large and often affluent digital social network, who can make a living from sponsored posts that advertise particular products or services.

“Building an authentic digital connection with an influencer gives you the opportunity to be very targeted and re-target your audience at scale in a hyperrelevant way for the consumer,” wrote Fabio Tambosi, a marketing director at Adidas.

Although social media is a recent phenomenon, Thorstein Veblen, an American sociologist and economist, set out his theory of “conspicuous consumption” in 1899, anticipating the influencer phenomenon of the 21st century.

Veblen theorized that people take cues about what to consume from the social class directly above their own. “The motive is emulation— the stimulus of an invidious comparison which prompts us to outdo those with whom we are in the habit of classing ourselves,” he wrote.

In other words, we desire to consume that which is just slightly out of reach. Kim Kardashian West, one of Instagram’s top influencers, agrees with that characterization. “An influencer really relates to a more everyday person and inspires them,” she said on the Business of Fashion Podcast in 2018.

$1 BILLION

$1 BILLION

Estimated sponsorships of Instagram influencers in 2017

Social media influencers are paid millions of dollars each year to hawk products to their specific audience of followers.

A wax sculpture of Kim Kardashian forever taking a selfie at Madam Tussauds in London. Photo: Shutterstock

Is sharing really caring?

For the first time in history, digital technology has given rise to a formal sharing economy, in which individuals can profit from “sharing” their personal goods or services with consumers who they may not know. For example, someone who lives in Madrid will be going to Paris to work for a month, and an American student will be studying in Madrid for the same amount of time. Airbnb facilitates the transaction so the American student has a nice place to stay, most likely cheaper than a hotel, with all the amenities of home, and the businessperson has an extra source of income.

What are the advantages of the sharing economy?

The sharing economy, in this case, is a clear optimization of resources, but in reality, this disruptive economic model has become a major challenge for policymakers.

Certainly, people have shared their assets with others throughout human history, but the internet has led to the construction of platforms that facilitate everything from connections with total strangers to payment and insurance. Considering that in 2007 neither Uber nor Airbnb even existed, the fact that the Chinese government wants the sharing economy to account for 10 percent of its national GDP by 2020 is simply jaw-dropping.

PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts that the value of the sharing economy will grow to $335 billion by 2025 from $15 billion in 2014.

Already, the sharing economy has taken root in lodging, transportation (cars, bikes, scooters), fashion, parking spaces, fundraising and services such as dogwalking, cleaning, delivery and so much more.

While the sharing economy creates many benefits for businesses and consumers, it also has given rise to many questions that have yet to be fully understood: How are these platforms affecting the economies of cities? How can the government tax and monitor revenues? Traditional industries like hotels and taxis are already regulated, so how can you make this competition fair? Is the so-called gig economy, which comes with people selling their services, threatening traditional labor?

The sharing economy marks a striking shift from the traditional economic model. Several businesses based on the idea have grown into multi-billion-dollar companies without being the provider of the main services; instead, they have become a facilitator of individual transactions.

ACCESS OVER OWNERSHIP

ACCESS OVER OWNERSHIP

From homes to drivers, clothing to scooters, companies have created platforms that allow consumers to access goods and services that may not have been on the market previously.

Photos clockwise: An Airbnb host welcomes a guest, a woman catches her Uber.

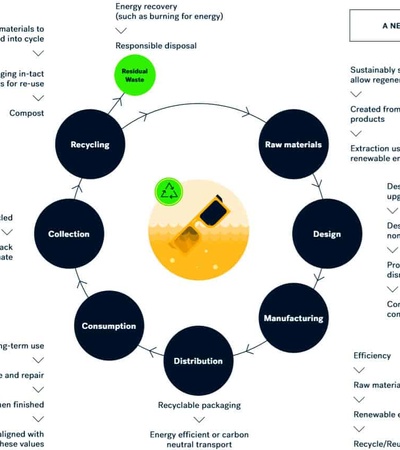

From planned obsolescence to the circular economy

### In 2017, the average waste in Europe was 487kg per person per year, according to Eurostat. With challenges such as the booming human population, climate change and a spectacular amount of waste generated by our current economic system, the circular economy is gaining traction as a new way to approach business and economics.

Looking beyond the current straight line of the “take, make then waste” industrial model and the idea of constant consumption, a circular economy aims to redefine growth, focusing on positive society-wide benefits. Inspired by the cycles of nature, it aims to design out waste and pollution, recycle and regenerate.

The circular economy also encourages innovation in terms of building capital from waste. A major study conducted by McKinsey Group and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that this approach could boost Europe’s resource productivity by 3 percent by 2030, generating cost savings of €600 billion each year, along with €1.8 trillion in other economic benefits.

Not only is this financially desirable and good for the environment as it reduces waste and the energy used to manufacture products that already exist, but it also reduces the risk of running out of finite resources.

Sea2See: Saving the ocean in style

Experts estimate that by 2050, our oceans will contain more plastic than fish and marine life. Barcelona-based Sea2see hopes to play its part in combating that phenomenon through fashion and showing the world a new type of business model. The company designs and produces optical frames and sunglasses entirely made with recycled marine plastic waste collected in collaboration with thousands of fishermen in Spanish ports.

Founded on the concept of the circular economy, the company has placed more than 100 containers in 30 ports in Spain, where fishermen are encouraged to deposit abandoned nets, fishing lines, ropes and the cringe-worthy quantities of plastic waste that they pull out of the sea. The company’s trucks collect around one ton of waste per day that is then sorted and broken down to create the glasses frames, made from 100-percent recycled plastic.

This zero-impact product is also a successful business model. Started in 2016, the company expects turnover in 2019 to reach €2 million – 30 times what it was in 2017 when its products first hit stores. Sea2See has been featured in media like Vogue and discussed in the United Nations.

In 2017, it won a $1 million grant from Chivas Venture, which funds socially responsible companies. As the spokesperson for Chivas Venture, Oscarwinning actor Javier Bardem even visited the company to find out how it works.

Plastic ocean waste was converted into these sunglasses. Photo: Sea2See

Javier Bardem examines the waste pulled from the sea which will be recycled into sunglasses. Photo: Sea2See

Conclusion: Looking at tomorrow, don’t forget yesterday

There is no doubt that the economy has changed substantially in just a matter of decades. Some of the biggest new companies offer services that could hardly have been conceived of in the 20th century. While economics as a field itself has also changed due to insights from psychology and access to large amounts of data, it remains rooted in the most basic concepts such as supply and demand or scarcity, and must continue to deal with questions such as currency values, employment, economic growth, inflation, and so on.

Already, this century saw a global financial crisis in 2007-2008 that came as a surprise to most economists. As it all gets more complicated, the challenges for economists may compound, which is why they must be prepared for what the future holds by not only understanding the present, but by drawing on lessons learned in the past. After all, what was true in Adam Smith’s day remains true today – all economic systems are a matter of belief.

ECONOMICS TAKEAWAYS

ECONOMICS TAKEAWAYS

OUR ECONOMIC DECISIONS ARE NOT ALWAYS RATIONAL

ATTENTION HAS BECOME A MAJOR COMMODITY

THE SHARING ECONOMY PRESENTS SIGNIFICANT BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES

IT IS POSSIBLE TO REDUCE THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF CONSUMPTION

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?