Is technology affecting our brains?

The internet has opened up a new mental environment that is impacting on every aspect of our lives in a way perhaps unprecedented in human history. People are understandably concerned about how this might be affecting the developing minds of toddlers, teenagers and adults alike. After all, every input that goes into our brains has some influence on their structure and neural connections.

The question is how significant is the influence of technology on humans?

Academics in the emerging field of cyberpsychology — which studies the effect of technology on our minds — along with neuroscientists, sociologists, educators and tech industry experts are deeply divided.

According to a survey by the US-based Pew Research Center, 42% of experts believe that all the googling, texting, tweeting, Facebooking, WhatsApping, Snapchatting, Instagramming, gaming, selfie-snapping and every other activity our tech-saturated world has created will have a largely negative impact on young people’s thoughts and behavior.

“We’re working with a moving target here to really figure out what’s going on. By the time we produce some research, maybe teenagers are no longer using Facebook; they’re using something else”Dr Kate Mills, Neuroscientist

On the other hand, 55% of the experts surveyed by Pew believed the benefits of being online would mostly outweigh the drawbacks. These anti-pessimists point to a striking lack of evidence for any disturbing consequences, highlighting the internet’s potential benefits and warning that trying to curb its influence could lead to the implementation of useless or even harmful policies.

Researchers are having to work hard to keep up. The ubiquity and the versatility of the internet poses problems for those trying to study it. For example, how do you recreate the real-world conditions of using the internet in the lab, asks Dr Ellen Newman, associate professor of psychology at IE University.

“How can you control for all other factors? How can you show causality — how much time will it take to show a change in performance and can you induce that while holding everything else constant for long enough?”Dr Ellen Newman, Associate professor of psychology at IE University

At the same time, the technology is new and changing all the time. “We’re working with a moving target here to really figure out what’s going on,” says Oregon-based neuroscientist Dr Kate Mills. “Considering how long it takes to publish findings, by the time something comes out, maybe teenagers are no longer using Facebook; they’re using something else.”

Clearly, we need to closely examine each emerging piece of research to see how it might fit into the overall puzzle and be aware that studies need to be constantly replicated. It might take years for the full picture to emerge, but the journey is one of the most fascinating in modern psychology and will prove key to understanding the capabilities and potential of tomorrow’s workforces and businesses.—

Scientists are working with a moving target when it comes to measuring technology’s impact on our brains.

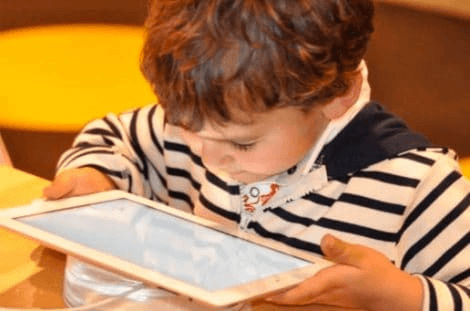

Toddlers and touchscreens

It’s an increasingly common sight in public places around the world. A parent whips out an iPad and hands it to their restless toddler so they can get on with poking at their smartphones and drinking coffee. But what effect might so much tablet time be having on that toddler’s developing brain? For tens of thousands of years the minds of human babies have been making the neural connections they need through interactions with real people and surroundings.

Now touchscreen technology in devices such as the iPhone and iPad is allowing babies as young as 18 months to press and swipe their way around a twodimensional tablet world.

The answers are only just emerging. A paper published in August 2016 by the Toddler Attentional Behaviours and LEarning with Touchscreens (TABLET) project, for example, failed to find any link between touchscreen use and walking and language development in infants aged between 19 and 36 months. But it did find a positive link with fine motor skills (stacking blocks) — something Dr Ellen Newman of IE University doesn’t find surprising. “Most screen time actions are small motor movements,” she says. “The more time you spend practicing something, the better you will be.” Nevertheless, she doubts its long-term effects on development.

What Dr Newman finds reassuring is that the study failed to find a negative link between touchscreen use and the time when toddlers say their first words. But future research needs to be focused on the quantity and quality of words being learned, which in her view are more important differentiators of later academic performance than just the onset of word learning and telegraphic speech. “Time that is spent engaged with any object that limits either exposure to conversation with others or even one’s own internal dialogue — private speech — can impact this vocabulary development and later verbal intelligence. That said, certainly a touchscreen used for games seems a lesser evil than videos and television shows.” So what should parents and educators do as they await further findings? The advice from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is that two- to five-year-olds should have less than one hour of screen time per day with a grown-up watching alongside, while those under 18 months should remain ‘unplugged’ with the exception of video calls to relatives.

“Time spent engaged with any object that limits exposure to conversation with others can impact vocabulary development and later verbal intelligence”Dr Ellen Newman, Associate professor of psychology at IE University

Nevertheless, parents who have to conduct more and more of their lives through such devices might find themselves struggling to comply with stringent limits. Perhaps instead of worrying about exactly how much time children spend glued to screens, we should — as the AAP suggests — simply be making sure other important aspects of their development are not displaced: that they are healthy, sleeping enough, talking to family and friends, doing well at school, pursuing interests and hobbies. There’s no escaping technology, but it shouldn’t be preventing us from experiencing the myriad offline activities that keep us healthy and happy.—

TODDLERS’ FINE MOTOR MILESTONE ACHIEVEMENT IS ASSOCIATED WITH EARLY TOUCHSCREEN SCROLLING

- 4.4of teenagers experience genuine difficulties with their internet use

- 5.2in males

- 3.8in females

- 95.6are functional usersPREVALENCE OF PATHOLOGICAL INTERNET USE AMONG ADOLESCENTS IN EUROPE: DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIAL FACTORS

Technology and young minds

1. No harm done?

Over the past 25 or years or so the rise of the internet has changed the lives of young people beyond recognition. And yet, they remain exactly the same. Young people still do schoolwork, listen to music, watch movies and talk to their friends. The only difference now is they can do all those same things without leaving their bedrooms via their phone, laptop and tablet screens. So how much does this matter?

The good news is that digital technology does not seem to be adversely affecting young people’s wellbeing in moderate doses, according to a recent study of over 120,000 15-year-olds in the UK. The research coauthored by Dr Andrew Przybylski of the Oxford Internet Institute even suggests that there could be a digital ‘Goldilocks zone’ of just the right amount of technology use where adolescents reap the benefits without being affected by the downsides (see infograph on page 20).

The study looked at the effects of watching TV and other media; playing video games; using computers to surf the web; and using smartphones for social activities. Results showed that wellbeing improved as the time spent on these activities increased — up to a certain point. Beyond that, wellbeing started to suffer as tech use rose. However, the effect was not dramatic, even at quite high levels — only about a third of the negative impact that skipping breakfast or not getting enough sleep might have on wellbeing.

2. Like minds

While tech use might not seem to be causing much harm, that’s not to say it isn’t changing behavior. One unique aspect of the online experience that seems to be impacting on young people’s lives is the ‘like.’ Found in various guises on different social media platforms, it differs from real-world social feedback in that it is quantitative rather than qualitative — and that seems to be having an effect on how young generations perceive and respond to online information.

By imaging their brains as they used an Instagramstyle app, a 2016 study found that a group of 13- to 18-year-olds were more likely to like pictures that already had a lot of likes — and that included those pictures they had taken themselves. “We saw that their neural responses were different as well,” explains study lead author Dr Lauren Sherman. “So the way that the brain was responding to the exact same images was changing when they knew that they were popular.”

Seeing that one of their pictures had a lot of likes triggered a response in brain circuitry involved in reward and reinforcement — specifically the one connected with learning about the world and motivating future behavior. According to Sherman, this doesn’t so much show that young people are suddenly privileging the ‘like’ and other forms of digital interaction over qualitative face-to-face feedback and withdrawing from the real world, as many educators and business leaders of older generations fear — there’s little evidence for that.

What it instead suggests is that the online sphere has become an important additional space for social interaction — and that it has its own different set of rules. Likes seem to help tune young people into what their peers believe they should or shouldn’t be doing: “Now instead of just looking to one another’s facial expressions or looking at the things that people are wearing to school or the way they are acting in that environment, they have this new environment where they can learn about what is cool or what is considered socially appropriate,” Sherman says. The internet thus seems to be adding to the complexity of our social worlds.

“I’m concerned with the nature of what people are doing in their multitasking and how this may be hindering development – particularly in the realm of inhibitory control”Dr Ellen Newman, Associate professor of psychology at IE University

Studies suggest reasonable technology use does not seem to be overly harming young people, but it may be changing their behavior in some ways.

3. Keeping control

All these likes and other little rewards that the internet dishes out — new messages, news stories, videos — can be hard to resist. The fear is that they might be affecting our ability to control our cognitive impulses. “You can think of this as putting your phone down and not picking it up if you have a notification or being able to concentrate for a long time, being able to multitask effectively,” says Sherman.

Academic evidence is limited, though one recent study of 13- to 24-year-olds in Finland found that those who tend to switch a lot between different media activities — watching YouTube videos while text messaging, surfing and doing their homework, for example — are potentially more distractible. In the experiment the subjects were shown a series of sentences and asked to determine whether they made logical sense or not. Some sentences were presented on their own; others were presented in pairs, with the subjects instructed to attend to only one of them. Those who had been identified as higher media multitaskers tended to perform worse in the cases when two sentences were shown together, suggesting they were more easily distracted.

Dr Ellen Newman of IE University says she is less troubled by internet multitasking’s impact on attention spans, and more about the dangers it might pose to people’s ability to tolerate boredom. She’s also worried about the types of tasks people engage in, which tend to be more of the checking social media than the experiencing major artworks variety. “I’m more concerned with the nature of what kids, teens and adults are doing in their multitasking and how this may be hindering their development — particularly in the realm of inhibitory control and, by extension, intrinsic motivation, grit, and resiliency.”

“Now instead of just looking to one another’s facial expressions or at the things that people are wearing to school, they have this new environment where they can learn about what is socially appropriate”Dr Lauren Sherman, Psychologist

Is digital multitasking good for us? Studies on the effectiveness of internet multitasking performed on adults have thrown up mixed results. For instance, one 2009 study found that high internet multitaskers performed worse in multitasking tests in the laboratory. But when another group of investigators replicated and extended that study four years later, they found the exact opposite. The results reveal one of the key problems in carrying out this kind of research: the technology is moving so fast that results of some experiments can change over time. Studies need to keep being replicated and extended for us to be confident what is taking place, neuroscientist Dr Kate Mills warns.

4. Total recall?

These days most of us, especially young people, are unable to remember so many bits of personal information as we once did. It’s now all stored for us on our devices, which have become our second brains. One survey found that 87% of people over 50 polled were able to correctly recall a relative’s birthday compared with fewer than 40% of those under 30 questioned.

When people expect to have future access to information, they’re less likely to recall the information itself and more likely to recall where to access it, research suggests. A study conducted by psychologists Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu and Daniel M Wegner in the US found that subjects asked to type in random items of trivia were less likely to recall one of the facts when they were told it would be saved in a folder on their computer than when told it would be deleted. However, the subjects were much better at remembering whether or not a fact had been saved and, if it had, in which folder they could find it.

But is this reliance on our phones and Google to store information we once committed to memory a cause for concern? Perhaps not — after all, it’s something we’ve always done. The only difference is that before we stored it in other people — a technique known as ‘transactive memory.’ Couples, for instance, often unconsciously divide up the things they need to remember; one might know when all the family birthdays are; and the other when bills need to be paid. Now we’ve extended that technique to the internet and smartphones – something some think could free up our mental capacities for more ambitious tasks.

5. Don’t be scared

So while the internet may not be unduly harming young generations — at least in moderate doses — it does seem to be making their lives more complex and in some cases even changing their behavior for the good, though we should remain attuned to its potential downsides.

Ultimately, it’s important to remember that technology is neither intrinsically good nor bad, but a multifunctional tool that psychology can help us get the most out of.

As Sherman sums up: “It’s really important for parents and educators to not be necessarily afraid of smartphones but really try to understand what it is that can be good about them, and teach good digital media literacy and good skills to young people.”—

A LARGE-SCALE TEST OF THE GOLDILOCKS HYPOTHESIS

THE POWER OF THE LIKE IN ADOLESCENCE

GOOGLE EFFECTS ON MEMORY: COGNITIVE CONSEQUENCES OF HAVING INFORMATION AT OUR FINGERTIPS

A DIGITAL ‘GOLDILOCKS ZONE’?

Is there such a thing as just the right amount of tech use, so we get all the benefits without the downsides?

On weekdays 15-year-olds’ wellbeing was found to peak after…

4H / 17’

of using computers

3H / 41’

of watching videos

1H / 57’

of smartphone use

1H / 40’

of videogame play

PSYCHOLOGY TAKEAWAYS

THE INTERNET DOES NOT SEEM TO BE UNDULY HARMING YOUNG PEOPLE’S BRAINS AND IS BENEFITING THEM TO SOME DEGREE

NEVERTHELESS, IT’S IMPORTANT TO BALANCE SCREEN TIME WITH OTHER ACTIVITIES

THE INTERNET SEEMS TO BE HAVING AN IMPACT ON OUR CONCENTRATION, MEMORIES AND HOW WE INTERACT SOCIALLY

FURTHER RESEARCH IS VITAL FOR US TO UNDERSTAND THE THINGS THAT ARE GOOD ABOUT TECHNOLOGY SO WE CAN REAP THE BENEFITS AND REDUCE THE DANGERS

Further reading

Online

- The Psychology of Cyberspace by John R. Suler

- Children and Adolescents and Digital Media

- Possible Effects of Internet Use on Cognitive Development in Adolescence by Kathryn L. Mills

- Effects of Internet use on the adolescent brain: despite popular claims, experimental evidence remains scarce by Kathryn L. Mills

Offline

- Psychology of the Digital Age: Humans Become Electric by John R. Suler

- It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens by Danah Boyd

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Some information has been compiled by third party sources that we consider to be reliable. However, we do not guarantee and are not responsible for the accuracy of such. The views of third parties set out in this publication are not necessarily the views of IE University and they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.