The art of managing a complex negotiation process is the ultimate skill in the fields of diplomacy and international relations. This report will consider the key concepts both newcomer and veteran negotiators or mediators would do well to bear in mind. Each negotiation has its own features but there is one universal truth: the final outcome depends not only on our own performance and behavior, but also on the other party’s. No one can fully control the negotiating process, but it is possible to maximize the opportunity for success.

Changing the world requires artful diplomacy and skilled negotiating at the highest levels, particularly at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

How much is it worth, and to whom?

When we negotiate, our main goal is to maximize the value that we get. But, in order to do so, we need to ask ourselves how much each element of the eventual deal is worth.

In international relations and in other walks of life, value is a matter of perspective; each individual, country or organization will place a different value on each item according to their own standards and circumstances. Taken to an extreme, we could ask how much our lives are worth. To us, and hopefully to our families, they are worth everything; but to a stranger, this is probably far from true. What value should be placed on a piece of land in the middle of the desert? If it is a religious site, then it is worth a lot to those who follow that religion, and possibly very little to others who do not. When we know that something is extremely valuable to somebody else, we realize that we can claim something in exchange, and this is where negotiations begin.

When negotiating, we need to consider the perspective of all the different parties and through active listening, we can actually get to understand the importance of those perspectives. If something is valuable to the other party, then it has intrinsic value, and we can claim something in return for it.

Essentially, we can divide the items that we will negotiate into those that are important for both parties and those with unequal importance. Understanding the value for both allows us to create a mental map that shows the level of complexity of each negotiating item, and the most likely tradeoffs. ‘Complex items’ are those that are important to both parties and where it is impossible to simultaneously satisfy the desires of the two. ‘Simple items’ are more important to one party than to the other.

When we know that something is extremely valuable to somebody else, we realize that we can claim something in exchange, and this is where negotiations begin.

For example, fishing quotas are usually subject to hard-nosed negotiations between countries. One side will claim that good fishing waters belong to them, while others stake claims to their right to exploit resources in international waters. Solving the dispute requires a setting of those boundaries and quotas on how much other countries can fish. In order to reach agreements, country negotiating teams will bring other elements to the table to create potential tradeoffs. One approach could be to include the quotas as part of a more general negotiation in terms of agriculture, fishing and other natural resources. A country may give up some of what it claims in terms of fishing if in return it gets a good deal for, say, wheat production. This will allow that government to subsidize its fishing industry if necessary. Without bringing several elements to the table, it would be impossible to make tradeoffs.

The key for value creation is to find items that have unequal importance for negotiating parties so that there can be tradeoffs.

While the exact terms of the Dutch purchase of Manhattan in 1626, reputedly for the value of 60 guilders, have been disputed by historians, it is possible to imagine an exchange of goods that were relatively inexpensive by European standards but that could be extremely valuable to the indigenous owners of the land. A contemporary deed has survived from the purchase of Staten Island a few decades later in which the Dutch are said to have traded “10 boxes of shirts, 10 ells of red cloth, 30 pounds of powder, 30 pairs of socks, 2 pieces of duffel, some awls, 10 muskets, 30 kettles, 25 adzes, 10 bars of lead, 50 axes and some knives.” In other words, a strategic patch of ground was sold to land-hungry settlers for a limited stash of worldclass technology. This is also value creation.

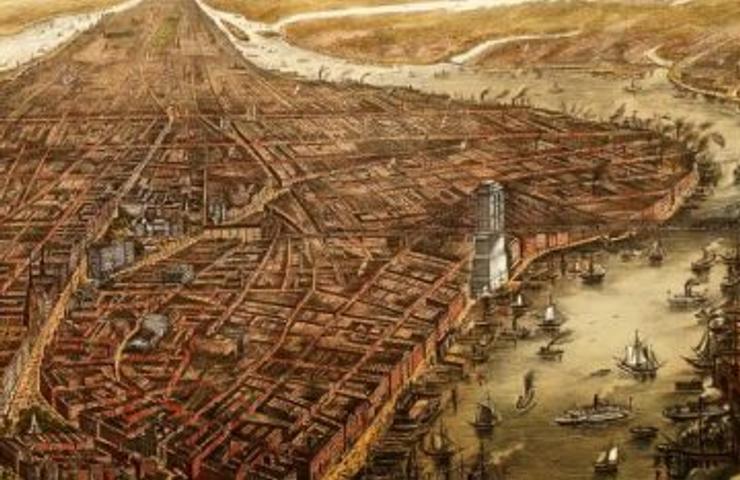

MANHATTAN ISLAND

A bird’s eye rendering of Manhattan Island from 1873 shows the city developing into the metropolis it would become in the 20th century. The sale of the island by Native Americans to Dutch settlers in 1626 has typically been portrayed as a case of naïve locals being outsmarted by astute colonizers. But, in the context of the time, both sides may have gotten what they needed most for a price they were able to pay.

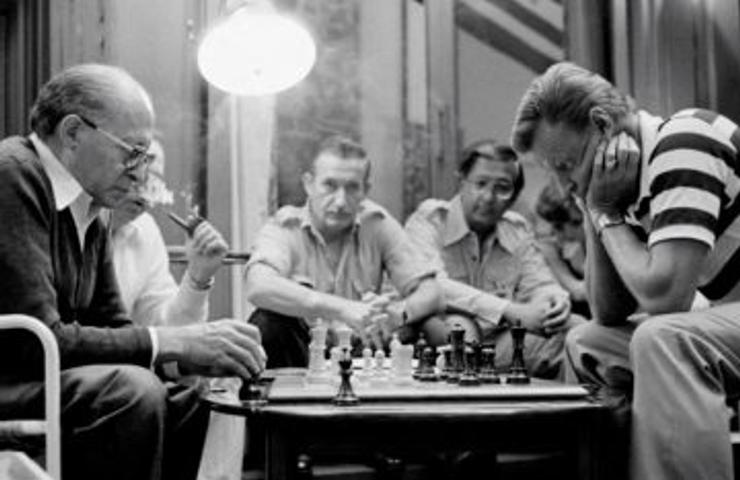

NEGOTIATIONS

Negotiations are more than a clash of different objectives and ideas. There are also opportunities to explore common ground and establish trust between participants. Here, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin (left) is pictured playing a game of chess with US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski during some downtime while the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt were being hatched in an almost two-week-long process of talks in September 1978.

Preparation and the serendipity factor

In the words of the Canadian educator Laurence J Peter, “If you don’t know where you are going, you will probably end up somewhere else.” Occasionally, an absence of expectations or preconceived ideas may lead to better results. But, in general, being unprepared is a recipe for unsuccessful negotiations. It is true that Columbus ended up in America because of his miscalculations about the location of Asia (the East Indies), but let’s not place our bets only on the serendipity factor.

The end result in any negotiation depends partially on luck and partially on our own performance, which is largely a consequence of how well prepared we are, negotiation skills are key. The random component is impossible to control so we should maximize our chances by being ready.

Columbus may have got his geography wrong, but he was sufficiently prepared in terms of seaworthy vessels and supplies to survive on the ocean long enough to reach the Caribbean.

Preparation in a negotiation involves understanding two key concepts: interests and objectives. Interests are our real needs and motivation, while objectives are our more tangible goals: what results am I trying to achieve in this particular negotiation? Preparation means, first, proper consideration of our own situation: what do I really want? How much am I willing/can I afford to pay? What are my true priorities? What are my ‛must have’ and my ‘nice to have’ elements? What are my dealbreakers? What are my alternatives? In other words, what is my backup plan in case this negotiation fails? What am I going to do or say?

First and foremost, preparation for negotiation means truly knowing your own objectives: What do I really want? How much am I willing to pay? What are my true negotiation priorities? What are my dealbreakers? What are my alternatives?

We also need to make the best possible estimate of what the other party wants: what is their limit (also known as the ‛reservation value’)? What are the triggers that will make them react? Ultimately, what do they want, and how can they achieve that? Is there anything that I can offer that has value to them? How much information do I want to share? When they say they have dealbreakers, are they just ‛very difficult’ or ‛truly impossible?’ What would they do if the talks break down?

We need to choose the right exchanges in order to create value and optimize the use of our resources. At first, we should try to understand our own priorities and those of the other party, finding ‛quick wins’ by exchanging items of unequal importance to both sides that will make both look like winners (win-win). Eventually, there will be other situations where it is impossible to create value for both parties, and then the negotiation becomes competitive (win-lose).

Strategy and tactics are both important and need to be aligned as part of the negotiation process. Strategy is more intangible: the thinking and the ideas. Tactics are totally tangible: how we implement those ideas. How do we plan to implement our negotiation strategy?

These considerations affect the physical preparation of the talks, starting with the place designated for meetings. Should the negotiation be held in one neutral space, or should one side push to hold the process in its territory? The eventual host should then consider every detail of the venue. Depending on the negotiating tactics to be implemented, the room could be laid out comfortably for a long, drawn-out process; or made less hospitable for a brief, possibly more confrontational faceoff. The provision of food and drink, the room temperature, and the timings of breaks are just a few of the ancillary considerations that can be borne in mind when hosting a negotiation.

Not being prepared may have irreversible consequences.

A decisive moment in the fall of the Berlin Wall took place partly due to a mistake announcement during a press conference. A spokesperson for the East German government, Günter Schabowski, said that legislation was being prepared to allow freedom for East German citizens to travel. When asked when the new rules would begin to apply, surprisingly, Schabowski was taken completely off-guard. “As far as I know, this enters into force… this is immediately, without delay,” he stammered. Many citizens took those words literally and massed at the border, where guards decided it was impossible to hold them back.

Günter’s blunder: After 28 years in which a divided Berlin had epitomized the Cold War deadlock, it was a slip of the tongue by an East German official during a routine press conference that opened a chink of light. Government spokesman Günter Schabowski said a border reform would be implemented “immediately,” leading citizens to mass at crossings on the evening of November 9, 1989. Photo: U.S. Department of Defense

CHECKLIST FOR A PERFECT NEGOTIATION

PREPARATION

• Understand the other party’s needs and circumstances

• Decide our own limits and guess theirs

• Be prepared with a potential proposal (the offer and how to phrase it)

• Prepare possible questions and answers to the other side’s questions

ETIQUETTE

• Verify dress code

• Smile

• Confirm time and schedule

• Greetings: shaking hands if culturally appropriate

• Room

PERFORMANCE AND OUTCOME

• Active listening

• Use of empathy

• Assertive behavior

• When closing, verify that other party is satisfied with the agreement

• Verify that the agreement fulfills your needs

ROOM SETTINGS AND LOGISTICS

• Enough light (ideally natural)

• Enough space

• Good temperature

• Water and snacks

• Schedule plenty of breaks

Critical mass and brinkmanship in European Union negotiations

The idea of a single currency had been floating around Europe for decades, but it was in 1989 that a firm plan began to take shape. France offered support to Germany for its reunification process in exchange for the latter’s support for what would become the euro.

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras exercised the small power’s biggest weapon; he walked away from talks and called a referendum on the terms of the bailout deal.

It was a win-win deal for both because what each received was more valuable than what they were giving up, and provided each with a strong internal explanation for why they would support the other’s cause.

The deal struck in Madrid in 1995 to create the euro owed much to the critical mass of the alliance between Germany and France. Once the two powerhouse nations were aligned, the rest of the countries followed because despite all of the logical fears about how the single currency would work in practice, few nations wanted to be the one left outside the magic circle at the center of European power.

Any large organization necessarily involves a huge amount of complex negotiations from its inception and throughout its existence. The European Union took decades to be crafted as we know it today, and it is still constantly subject to changes and new proposals. On top of the periodic, overarching treaty processes (with Lisbon, Nice and Amsterdam being the last three), there are permanently ongoing negotiations regarding the accession of potential new member states, talks between members, decision-making on contingencies and debates over policy-making.

In multilateral negotiations like those that shape the EU, it is important to understand each party’s interests and objectives. But whose interests and objectives do we actually mean? Because it is not a nation as such that votes in the European Parliament or in other decision-making bodies, but rather its representatives. Those who govern have a huge incentive to shine and make an impression in the eyes of their citizens, and are unlikely to care so much about the opinion of those of other countries. They need to have a story to sell internally because, at the end of the day, it is their own citizens who will decide whether to return them to power.

A crisis amongst eurozone countries in 2015 showed how complex nations’ positions can be in talks whose results play out on both the international and domestic stages. The key players were the Greek government, in need of a bailout to remain solvent and stay in the euro but wishing to avoid further slashing of public services to meet EU deficit guidelines; and Germany, the eurozone’s financial power who acted with reluctance to bankroll the Mediterranean state amongst a heated debate regarding Athens’ budget management during the previous years.

While a ‘No’ vote would not automatically signal the country’s exit from the eurozone — a Grexit — the reality was that no deal between Athens and the rest of the single-currency bloc would see the country become insolvent.

Disadvantaged in terms of hard financial muscle, Tsipras turned to democratic soft power. The 61% ‘No’ vote in the July 5 referendum put out a clear message: financial hawks in northern Europe represented by countries such as the Netherlands and Finland must realize that by imposing their austerity measures, they would be in confrontation with the will of the majority in the cradle of European democracy.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel had to balance her own domestic pressures to be seen to be tough on Greece with her personal legacy as de facto leader of the European project. Merkel also had her own hawk to deal with. Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble had drawn up a secret plan that included suspending Greece from the euro for five years and setting up a trust fund of Greek assets to be held in Luxembourg.

Through the day of the last-ditch Brussels summit meeting on Sunday July 12 and deep into the early hours of Monday, Tsipras and Merkel went head to head. The bruising all-night session, refereed by then-French President François Hollande and European Council President Donald Tusk, finally produced a deal; imperfect for both sides, but a deal, nonetheless. Funds would be released to allow Greece to meet imminent debt repayments in return for Tsipras’s government reforming the tax and pension system and liberalizing the Greek labor market. The €50-billion trust fund would not be based in Luxembourg, but in Athens.

“The advantages outweigh the disadvantages,” Chancellor Merkel concluded.

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS TAKEAWAYS

THE KEY FOR VALUE CREATION ARE ITEMS WITH UNEQUAL IMPORTANCE FOR NEGOTIATING PARTIES SO THAT THERE CAN BE TRADEOFFS

START PERSUADING SUPPORTERS AND NEUTRALS. ONCE YOU HAVE BUILT CRITICAL MASS, OPPONENTS WILL FEEL UNCOMFORTABLE SAYING “NO”

PREPARE YOUR OWN OBJECTIVES, STUDY THE OTHER PARTY, AND HAVE A BACKUP PLAN

CONSIDER IN ADVANCE THE CONSEQUENCES OF YOUR COMMITMENTS, ESPECIALLY IF THEY ARE PUBLICLY STATED

Further reading

- Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In by Roger Fisher, William Ury and Bruce Patton

- Getting Past No: Negotiating in Difficult Situations by William Ury

- Getting More. How to Negotiate to Achieve Your Goals in the Red World by Stuart Diamond

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Some information has been compiled by third party sources that we consider to be reliable. However, we do not guarantee and are not responsible for the accuracy of such. The views of third parties set out in this publication are not necessarily the views of IE University and they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.